Most of what I write about PKM and Second Brain focuses on relating the vast body of high-quality research on academic note-taking to what many of us do outside the classroom as independent learners. The nonclassroom use of notes and related strategies for making and using notes has been termed Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) by those offering self-improvement advice. The PKM area is driven mainly by common sense. I cannot find focused research to inform this transition, but I have been investigating classroom note-taking and studying for decades and now focus on synthesizing findings from one area to support or evaluate strategies in the other.

The classroom research primarily focuses on the interrelated tasks of taking and reviewing notes, and, more recently, on handwritten versus keyboarded notes. With PKM, there is a greater emphasis on continually revisiting stored notes. This topic has not been emphasized in the research with classroom notes, but some studies do exist and it is this more minimal area I want to explore in this post. Again, the advantage is in the research evaluating efficacy and what cognitive processing is enabled or encouraged in modifying original notes in various ways.

I now primarily focus on note-taking on a digital device. While studies have focused on whether handwriting is superior for initial learning, approaches that encourage a deeper look at your notes reveal a powerful consensus that transcends the medium: there is unique value in notes that involve not just how notes are taken, but in how notes are revised.

This insight provides a critical link between academic research on learning and the practical strategies of Personal Knowledge Management (PKM). If your goal is to move beyond simply collecting information to actively building a knowledge base, you must embrace the often-overlooked middle stage of note-taking: revision and restructuring.

The Three-Stage Model: Beyond Capture and Review

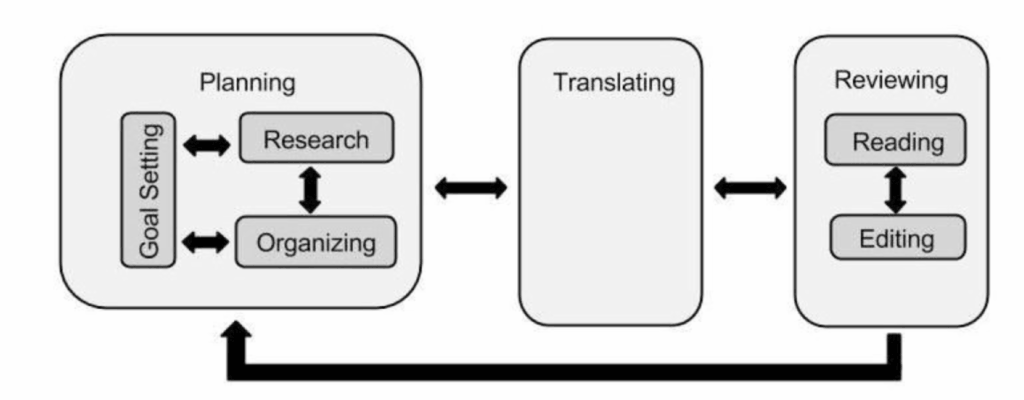

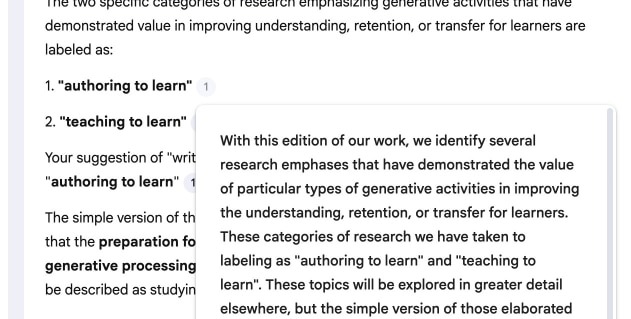

Traditional study advice often reduces note-taking to two phases: recording during a lecture or reading and reviewing before an exam. However, classroom-oriented research by Luo et al. (2016) and Flanigan et al. (2023) suggests a more productive, three-stage process: recording, revision, and review. This intermediate revision stage is where the magic happens – where passive information capture transforms into active knowledge construction.

The research on this topic is compelling. A study by Cohen et al. (2013) demonstrated the causal role of a note-restructuring intervention in improving student learning. Students who were required to restructure and reorganize their notes, summarize the main point, and elaborate on a detail performed significantly better on exams. The researchers concluded that this process was essential for students to “make information one’s own, by processing it, restructuring it, and then presenting it in a form so that it can be understood by others (or by oneself at a later point).”

Sounds very similar to the pitch for PKM strategies. Revision isn’t just about neatness or completion; it’s about deepening understanding through elaboration, incorporating entirely missed ideas, and creating retrieval cues that activate deeper memory networks.

From Note-Taking to Note-Making

In the world of PKM, a distinction is often made between note-taking (the act of recording external information) and note-making (the act of processing that information into a new, personalized, and connected knowledge item). The revision stage is precisely where you transition from a passive note-taker to an active note-maker.

PKM methodologies, such as the Zettelkasten, emphasize that a permanent note should be able to stand alone, expressed in your own words, and contain enough context to be meaningful without referring back to the original source. This is a direct parallel to the restructuring intervention that required students to summarize the main point and elaborate on a detail.

When you revise a note in an academic setting, you are performing the cognitive work that drives learning: elaboration (connecting new ideas to what you already know), organization (clarifying underlying structure and identifying themes), and synthesis (cross-referencing the new idea with other sources). Without this deliberate revision, you risk falling into a common trap: mistaking familiarity for understanding. Most learners fail to organize their notes after class because they recognize the content and mistakenly assume they have mastered it. Active processing, often based on concepts such as generative processing, is the focus of much research.

The Longhand Advantage in Revision

The handwriting versus keyboard comparison recurs in studies of revision. Some, but not all, studies contradict my assumptions about the advantages of a digital approach. Flanigan et al. found that longhand note-takers added three times as many complete ideas to their notes during revision compared to computer note-takers, and twice as many partial ideas. These researchers argue that handwriting engages deeper cognitive processing during initial recording, making those notes more effective retrieval cues when revisited later.

However, the digital environment isn’t without its strengths. Research by Cojean and Grand (2024) found that students who take notes on a computer are more likely to reformat their notes during revision. The ease of manipulating text digitally encourages a strategy where transcription is prioritized during capture, and the deeper work of reformulation and organization is deferred until the revision stage.

In a modern PKM system, this deferred processing is not a weakness, but a feature. Digital tools make it effortless to refactor (break long notes into smaller, single-idea notes), link (create hypertext connections between related ideas), and organize (file processed notes into multiple collections). The digital environment transforms revision from a tedious manual task into a fluid, creative act of knowledge gardening.

Making Revision Your PKM Habit

Those offering practical advice for students seem to recommend a structured approach to the revision stage. Treat it as a non-negotiable part of your workflow, not an optional step before an exam. Here are three practical revision strategies:

The “Foot” and “Socks” Method: Immediately after capturing a new note, summarize the main point in a concise “foot” (like a title or summary field) and elaborate on a key detail in the “socks” (the body of the note). This forces immediate processing and mirrors the Cohen et al. intervention.

The Atomic Note Refactor: If your initial note is a long transcription, dedicate time to breaking it down into smaller, single-idea notes. Write each new note in your own words and link it to at least one other existing note in your system. This practice creates the interconnected knowledge web that makes PKM powerful.

The Cross-Reference Check: When revising, actively search your existing notes and collections for related concepts. Link your notes back to original sources to resolve ambiguities and provide context. Make an effort to relate lecture content to what appears in your textbook. This is the moment to create connections that integrate new information into your existing knowledge structure, moving beyond simple storage to true knowledge management.

Schedule dedicated revision sessions, ideally spaced throughout your learning timeline rather than clustered after completion. Consider handwriting your first draft or deeply processing material before digital capture to maximize the depth of your initial notes. Make note revision an ongoing habit, integrated into your learning cycles rather than a single end-of-lesson task.

Conclusion

By making revision a deliberate and structured part of your note-taking, you stop merely collecting information and start actively building a powerful, interconnected knowledge base that supports long-term learning and creative work. The research is clear: revision elevates note-taking from passive transcription to active knowledge building. It transforms fragmented jottings into complete, interconnected ideas ready for recall and application.

For anyone committed to lifelong learning and effective Personal Knowledge Management, understanding and embedding the practice of careful, thoughtful revision into your workflows will create richer, more useful knowledge bases – helping you learn smarter, not just harder. Classroom studies encourage a structured approach and often control such activities through assignments. Independent learners must take personal responsibility to produce similar results. The missing link in your note-taking isn’t the tool you use or the speed at which you capture—it’s the intentional work of revision that transforms information into true personal knowledge.

References

Cohen, D., Kim, E., Tan, J., Winkelmes, M. (2013). A note-restructuring intervention increases students’ exam scores. College Teaching 61(3), 95-99.

Cojean, S., & Grand, M. (2024). Note-taking by university students on paper or a computer: Strategies during initial note-taking and revision. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(2), 557-570.

Flanigan, A. E., Kiewra, K. A., Lu, J., & Dzhuraev, D. (2023). Computer versus longhand note taking: Influence of revision. Instructional Science, 51(2), 251-284

Luo, L., Kiewra, K. A., & Samuelson, L. (2016). Revising lecture notes: how revision, pauses, and partners affect note-taking and achievement. Instructional Science, 44(1), 45-67.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.