I am interested in the process of writing. Originally, I was interested in my own writing and how I might write more productively and efficiently. Gradually., I became interested in student writing. My first interest was in what I would describe as writing to learn and this focus came about because I was convinced what was called Web 2.0 (I called it the participatory web) provided a practical way for individuals to express themselves for an actual audience. In doing so, it made sense that the process of visible expression required deeper thought and a better understanding of what you wanted to share. An interest in the role of technology in learning to write and in collaborative writing followed. I hope this makes sense. There are multiple components here and I am trying to outline how these components are interconnected and came to be as much for myself as for anyone who reads this description.

As I have spent time learning about writing and how the process might be conceptualized and developed, my way of thinking about what writing involves has expanded. This expansion has been useful because it allowed me to include a long-time interest in student and personal note-taking in how I came to think about writing. Recently, I have been reading a book entitled “How to take smart notes”. The full title which is much longer explains that the book is really about writing as a broad process that begins in reading/listening, moves to note-taking, and then explains how learning and creativity are involved in the progression to generating a text for others. I have found that the full model offered me a lot to consider and to write about. Eventually, some of the writing will likely appear on this site. For now, just accept my recommendation for this book.

Anyway, the topic of note-taking plays a crucial role in this book and especially a type of note-taking that I would describe as an investment in the future of personal understanding and knowledge building. By investment, I mean that the process described involves the immediate accumulation of interesting ideas and important concepts in what the text describes as a slip box. This was a descriptive term used by the originator of the process outlined in the book to describe a physical box in which short, but well-written statements were saved. These “notes” were then linked to other notes in the box through a notation system. Eventually, an author could use these linked statements to create an informative document. Of course, many of us can immediately imagine how to use technology to apply this system and this is part of the message of the book’s author, but there are some basic ideas that are of greater general value. For example, the “slips” amount to more than the highlights or edge of page annotations created while reading, but rather well-formed and personalized statements created from primary sources. Such brief summarizations or insights are closer to a core product of writing than a physical copy of a snippet of the original.

One of the comments from the book and a great example of the cognitive behavior that is at the core of why the writing process is productive was provided in a “side observation” offered by the author. This observation was that while the author kept offering suggestions for how technology might be a great way to implement the ideas from the original “slip box” process, the author suggested that the process of writing notes by hand might be more beneficial than the digital equivalent. I have been having a kind of “meta” experience as I write about my reading and relating of this idea. The author is writing about how to find productive associations among ideas and I see such an association in what I already knew about the logic of taking notes on paper (I have taken notes by hand in a decade) and why I still advocate for digital processing of the entire process of idea storage to final written products.

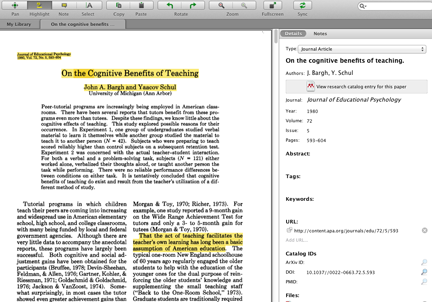

The author cites a study (Mueller & Oppenheimer, 2014) in support of his position. I have read this study and have existing notes on the pdf of the article I store in my collection. There were three studies in this article comparing performance (comprehension and application) following exposure to an audio lecture and note-taking. All three studies involved one group that took notes by hand and another that took notes on a computer. There are other multiple studies on this issue and because I have a bias toward the value of technology I look for several things in the methodology of studies arguing for the benefit of taking notes by hand. Is the performance test immediate or delayed? If the test is delayed, are learners allowed to review their notes before taking the exam. In comparison to just listening or reading, note-taking offers two potential benefits – external storage and a task that may involve more productive processing of the input. Taking notes on a computer typically results in more content being recorded as most of us can take notes faster on a computer than by hand. If I am reviewing my class notes weeks later, I want a more detailed account. Mueller and Oppenheimer found greater detail in keyboard note-taking, but in their third study with a delayed exam found a benefit for taking notes by hand. They argue that when faced with the reality that you cannot possibly keep up, handwriting requires you to summarize and record key ideas producing the best long-term value. This ends up being the argument used in advocating handwritten notes for the slip box. Summary and key idea notes are what is valuable in writing. It is kind of a less is more argument.

I am still not a believer although I buy the notion that at some point you need to process the original input for personal meaning. The proposal that an approach that is slower (handwriting) and as a consequence encourages deeper processing (also slower) seems to argue for some approach that is must address these two limitations. Both slow and slower strain the limits of working memory. The issue with deeper processing is when this more productive processing should happen – during the presentation (as saved to summary notes) or when studying more complete notes. Here is my criticism of the Mueller study in making the suggestion for practice that appears to be made and is picked up by Ahren’s book. . Allowing a few minutes to review notes before taking an exam is not my idea of studying for an exam. Certainly, if this is all of the time allowed good summaries would be most helpful. However, if I had a day or so and at least the night before to study a large body of lecture notes I would prefer access to notes that are more complete. When doing this, I would prefer more complete notes I could think about (process for meaning and application).

I think there are tools appropriate to the task of taking digital notes and providing a better delayed experience. The two recommendations that follow record the audio of a presentation (this is the input Mueller uses) and allows for the taking of notes. The apps link the notes to locations in the audio. If on reexamining the notes to see if they make sense (hopefully initially close in time to when the notes are taken) something does not make sense. Small portions of the audio can be replayed for additional processing.

Ahrens, S. (2017). How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking – for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers

Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological science, 25(6), 1159-1168.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.