When a technology offers advantages and disadvantages, the decision-making process can be quite complicated, especially when oversight cannot be guaranteed. For example, many states now ban cell phones, making a use such as telling parents when the schedule for after-school activities has changed difficult. The advantages and disadvantages vary with the field of application and my interests have mainly been focused on education. Just to be clear, by this I mean learning in general, not just the type of learning that occurs under supervision or is associated with educational institutions.

The generic educational situation that raises concern involves tasks undertaken to encourage both skill development and knowledge, and includes a requirement that demonstrates that the task has been attempted by the existence of some product. In educational settings, such products might result from homework or class activities, or simply by visible demonstrations of activity. The issue with AI is that in many cases, such as problem sets or documents of various types, these same products could be generated by AI, avoiding the cognitive activity of the learners. The phrase “cognitive offloading” has been used to describe this alternative form of product creation. Teachers might simply call it cheating. Cognitive offloading itself can be a desirable or undesirable option, requiring decisions regarding when it is appropriate and efficient, and when it is a detriment.

While cognitive offloading to avoid learning tasks seems an obvious problem, little actual research exists to demonstrate the damage done. Some would argue that if technology can replace an activity and that technology is readily available, why bother to “learn” the skill in the first place? Why learn information if your cellphone can allow you to search for information when it is needed? Why learn basic calculation skills when you cellphone can also serve to do mathematical operations? There are responses to these challenges, sometimes offered by students or parents, but this analysis would take this post in a direction I did not intend.

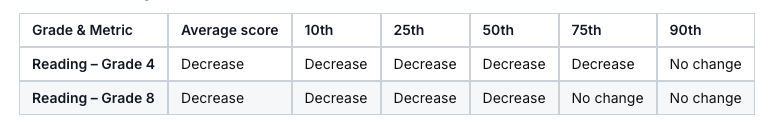

Here, I want to focus on learning to write and writing to learn by discussing a different learning task. This may sound unnecessary, but at present, there is a reason to take this approach. The justification for being indirect is that writing is a complex skill consisting of multiple subskills, and we learn to become competent at even a basic level over years and not weeks or hours. We are investigating an alternative to the traditional methods of instruction that can be subverted now, and we cannot rely on experience to help us evaluate and tease apart how the development of subskills are impacted. The insights and evidence of the potential damage done would take to long to emerge. As one perspective, consider the lingering impact of COVID on learning. What about the move to online learning did we not anticipate and what consequences are we still trying to mitigate?

AI in Learning to Code

Shen and Tamkin had an opportunity to investigate the impact of AI with adult programmers learning to make use of a new library. Think of a library as a collection of functions (tools to perform specific and commonly used tasks). Instead of having to write code to accomplish common tasks each time a programmer encounters a need, libraries allow programmers to call prewritten code snippets. It takes some work to make use of a library – what functions are available, how do you call the function you want, what inputs and outputs are involved and how are these integrated with the code you write yourself? The researchers recognized that the learning coders had to do to make use of a new library provided an opportunity to study how AI could help and hinder learning a complex process.

Shen and Tamkin studied actual programmers as they worked to learn a new library. They suggested that the process be viewed as a tutorial including both background information and simple programming tasks. Programmers were assigned to a control and a treatment group, with the treatment group having access to AI. The learning phase concluded with an assessment evaluating multiple concepts and skills. Video of treatment group participants was collected to document how each individual used AI and worked on the programming exercises.

The researchers found that the treatment groups did not differ significantly in the time spent learning, which they found surprising. On the post-test, the largest group differences were in debugging skills. Smaller skill differences were found for code reading and conceptual understanding. Those without access to AI made more coding errors on the practice tasks, spent more time practicing debugging, and ended up with better skills on the outcome evaluation. How AI was used differed greatly with some simply asking AI to solve the coding challenges and others who only asked higher-level questions of the AI tool. Some users had the AI tool solve the coding challenges and then retyped the solutions themselves (rather than copying and pasting). This was not an effective strategy.

Generalizing from the coding study

I have spent considerable time both coding and writing and I have always found the processes to have similarities. While others may find this a strange observation, I have always said that coding and writing were the two professional tasks I learned I could not perform later in the evening if I wanted to get a good night’s sleep. Reading was fine. Grading was fine. Something about both coding and writing was cognitively stimulating, making it difficult to sleep.

The application of AI to complex skills is interesting, but difficult to study. Clearly, a single skill would seem very unlikely to be developed if a learner could completely substitute AI for practicing the skill. However, it seems possible that learning a multiple-component skill such as reading or coding might benefit from replacing specific components with AI under certain circumstances. We have limited cognitive capacity and substitution for some components of a complex task could allow the remaining components to receive more attention until well learned.

Learning to write might represent an example. I have often referred to Flower and Hayes’ writing process model when describing the components of writing and writing to learn. The use of AI to offer content to provide the basis for a writing task and perhaps even to offer a structure to guide the organization of a writing product could free up capacity to focus on lower-level skills such as spelling, grammar, and coherent paragraphs. In contrast, I typically use Grammarly while I write to allow to move more quickly while relying on this AI tool to alert me to possible spelling and grammatical improvements.

Part of what Shen and Tamkin observed in their qualitative observations of the different learner-imposed focus of AI and the relationship of differences to what was learned or not learned offers a related perspective. Debugging is an important lower level coding skill and having AI debug code appeared to limit a coder’s ability to debug when working without AI.

Suggestions for Learning to Write and Writing to Learn

AI can support both “learning to write” (developing writing skill) and “writing to learn” (using writing to deepen understanding), but depending on which writing skills are the goal best practices should differ.

Learning to write: skill development

Here AI should be thought of as a coach, not a ghostwriter.

Emphasize feedback: Tools like Grammarly give immediate feedback on grammar, syntax, cohesion, and organization, helping students revise iteratively while concepts are still fresh.

Structure and separate subprocesses: Generative tools can help students brainstorm ideas, outline structures, or identify expectations for different types of writing (e.g., sample introductions, transitions).

Process?first policies: “Writing first, AI second” approaches ask students to draft independently, then use AI for critique and revision. When coders used AI in the Shen and Tamkin, this is the general theme that seemed most successful.

Writing to learn: thinking with text

When the goal is conceptual understanding of content knowledge, AI is best used to amplify reflection, not replace it.

Clarifying concepts for the writer: Students can ask AI to reexplain readings, generate examples, or pose practice questions, then respond in their own words, using writing as a space to consolidate understanding.

Challenge personal understanding: AI can generate counterarguments, alternative explanations, or “what if” scenarios that students must address in writing, pushing them beyond summary toward analysis. Why do others disagree with the summary I am creating? What can I offer to support my position and what are the limitations of the alternative?

Shared design principles

There are some guidelines these goals for writing. Across both purposes, similar design choices matter.

Make process visible: Require artifacts – notes, outlines, draft histories, and brief process memos about when and how AI was used. Document the transition from any use of AI to products student has generated.

Align AI roles with goals: For skills (learning to write), let AI focus on feedback, exemplars, and mechanics; for content learning (writing to learn), keep generative help outside the main composing space and treat it as a prompt.

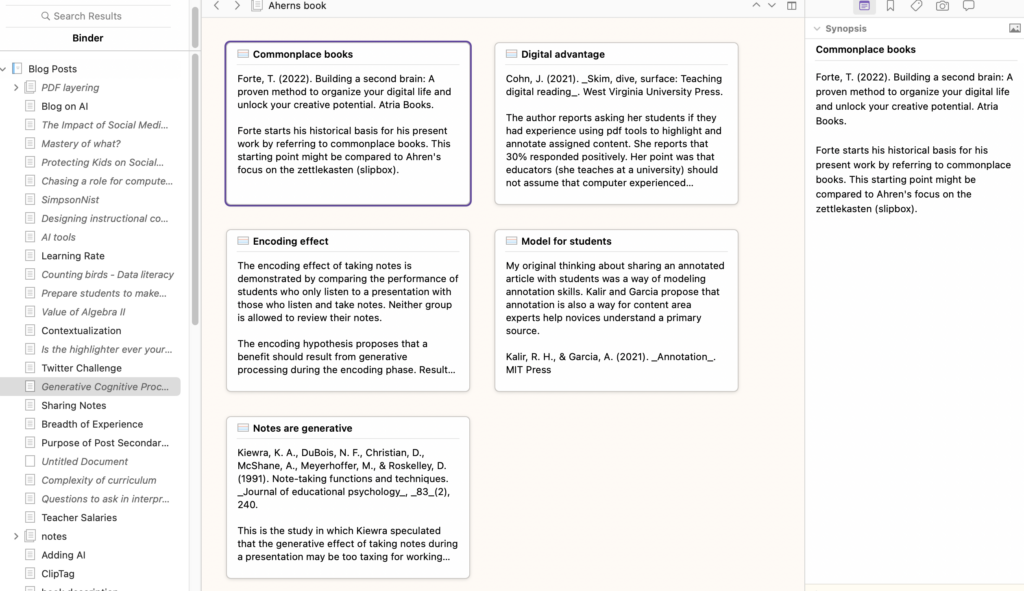

Previous analysis of technology and the writing process

Sources:

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition & Communication, 32(4), 365-387

Shen, J. & Tamkin, A. (2026). How AI impacts skill formation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2601.20245 (this study has yet to officially be published)

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.