This post assumes you understand the basics of what is referred to as the “writing process” and perhaps have read my previous post explaining what the writing process is and why it is valuable to educators and researchers. One additional role I proposed in that post was that the components of the writing process would be helpful in identifying technology tools that would support the various components of the Writing Process. This post identifies these tools and explains how they might be applied.

Before I get to my effort to associate specific technology tools with specific writing processes, I thought it useful just to make a case for writing using a word processor. The benefits are too easy to overlook, and opportunities may be ignored.

I assume you complete many of the writing tasks you take on using a word processing application. Do you do this because you assume this approach makes you more efficient or do you assume this approach makes you a better writer? Maybe you have never even thought about these questions. However, when functioning as a teacher and asking your students to engage in activities in a particular way, it may be helpful to consider why the approach you expect students to use will be productive. Often, to realize the full potential of an activity, the details matter and some insight into why an approach is supposed to be productive may be helpful in understanding which details to track and emphasize. The following comments summarize some ideas about the value of word processing and of learning to write using word processing applications.

In learning, as in other areas of life, you seldom get something for nothing. Still, a logical case has been proposed for how simply working with word processing for an extended period may improve writing skills and performance. One interesting proposal by Perkins (1985) is called the “opportunities get taken” hypothesis. The proposal works like this. Writing by hand on paper has a number of built-in limitations. Generating text this way is slower, and modifying what has been written comes at a substantial price. To produce a second or third draft requires the writer to spend a good deal of time reproducing text that was fine the first time, just to change a few things that might sound better if modified. Word processing, on the other hand, allows writers to revise at minimal cost. You can pursue an idea to see where it takes you and worry about fixing syntax and spelling later. Reworking documents from the level of fixing misspelled words to reordering the arguments in the entire presentation can be accomplished without crumpling up what has just been painstakingly written and starting over.

What Perkins proposed was that writers can take risks and push their skills without worrying that they may be wasting their time. The capacity to save and load text from some form of storage makes it possible to revise earlier drafts with minimal effort. Writers can set aside what they have written to gain new perspectives, show friends a draft and ask for advice, or discuss an idea with the teacher after class, and use these experiences to improve what they wrote yesterday or last week. What we have described here are opportunities—opportunities to produce a better paper for tomorrow’s class and, over time, opportunities to learn to communicate more effectively. The same is true for writing outside of an academic setting. Is not a bad idea to set a written product aside and then return to read it once more before sending it off. Often, errors become apparent and new ideas surface.

Do writers take the opportunities provided by word processing programs and produce better products? The research evaluating the benefits of word processing (Bangert-Drowns, 1993) is not easy to interpret. Much seems to depend on the experience of the writer as a writer and technology user and on what is meant by a “better” product. If the questions refer to younger students, it also seems to depend on the instructional strategies to which the students have been exposed. It does appear that access to word processing is more beneficial for older learners. General summaries of the research literature (Bangert-Drowns, 1993) seem to indicate that students make more revisions, write longer documents, and produce documents containing fewer errors when word processing. However, the spelling, syntactical, and grammatical errors that students tend to address and the revision activities necessary to correct them are considered less important by many interested in effective writing than changes improving document content or document organization. The natural tendency of most writers appears to be to address surface level features. This is especially true with less capable writers.

Writers appear to bring their writing goals and habits to writing with the support of technology. Beginning writers and perhaps writers at many stages of maturity may not have the orientation or capabilities to use the full potential of word processing, and their classroom instruction may also emphasize the correction of more obvious surface errors. Thus, there are typically improvements in the products generated when working with word processing tools, but the areas in which younger writers seem to improve are not necessarily the most important ones

Tools specific to writing components

Here are the types of tools we see as supporting individual writing processes. We list tools using general terms as specific examples of a given category come and go. Our online resources include more detailed information about specific tools you might try.

Planning – Research

Authors write based on what they know and what they can discover. What they discover could come from books, conversations with others, data collection and analysis, or Internet searches. Internet searches are a common practice, and some writing environments embed search access within the writing environment and even suggest topics and links based on the content being written. Of course, opening a browser or a second tab when writing in a browser in order to conduct a search is a simple matter. For those of us writing in specialized areas and needing source material such as scientific sources more powerful fused search tools are available and it seems new ones emerge daily. Google Scholar provides access to the resources I cite. I can search for research publications on a specific topic and use a hit on a useful resource to locate even more recent sources that cite the initial find. There no restrictions or subscriptions that apply to Google Scholar so there is no reason to not give it a try. Research Rabbit, LitMaps, Semantic Scholar, and several similar tools compete for the attention of researchers.

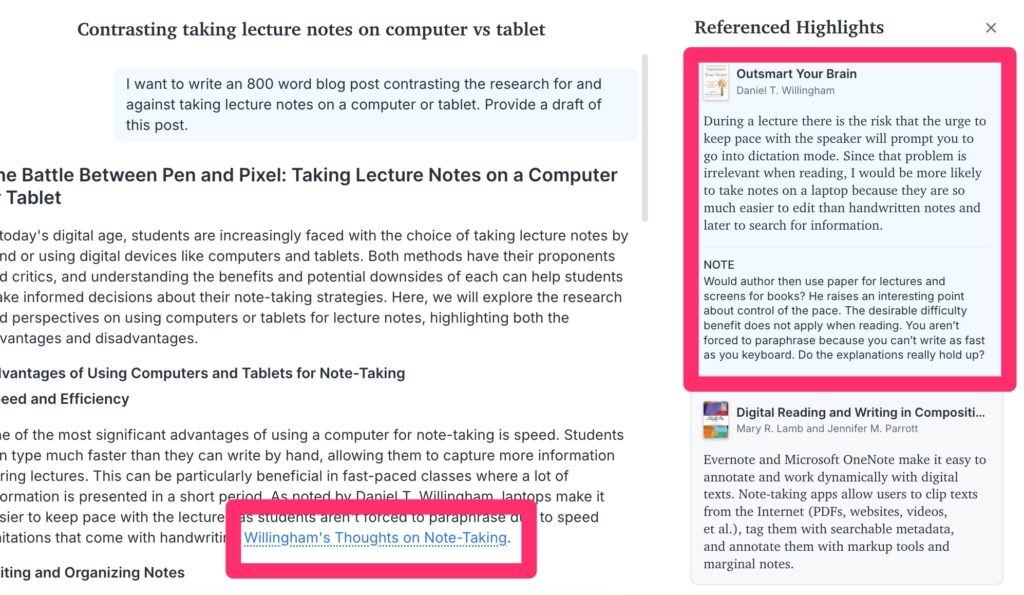

Locating information to be used in a future project or to improve an existing project also typically involves temporary storage of content and the information necessary for the attribution of useful sources. There are certainly nondigital ways to accomplish these tasks. Information could be entered in a notebook. There are now many digital tools that can be generalized to store notes or are specialized in some way. Writing systems may have built-in note taking, storage, and organization tools. Perhaps you have taken notes on cards. There is a digital equivalent. Scrivener is a writing environment and like writing tools, you would be more likely to have used is really a combination of tools. These “cards” can be organized and reorganized and offer the advantage of being searchable and other opportunities not available in the paper equivalent; e.g., copy and paste from source content, search, audio or image storage, duplication and off-site storage of resources so the work completed is not lost. The idea is that you can accumulate these “notes” and then organize them for use as you write.

Perhaps you just use a notebook to accumulate notes as you prepare for a writing task. There are many tech tools that serve a similar function and offer some enhancements not available with paper resources. Apple Notes comes with the Apple OS and iOS so that you can access your notes across Apple devices. Apple has taken to describing this tool as a way to store “forever notes”. With what could be unlimited storage, why discard notes after the project the notes were intended to support is finished? Perhaps the notes might be useful in the future. To make this practical, the tool must be capable of more than storage. You need to be able to find what you stored when useful and this involves powerful search, tags, and collections. There are many tools based on a similar concept (e.g., Evernote, OneNote, Notion, Google Keep).

Ideas as building blocks

One subcategory of note taking tools encourages the isolation of individual ideas or concepts. Think of note cards. I prefer to imagine Lego Blocks as ideas proposing that anyone familiar with these blocks appreciate how the blocks can be reused to build many different things. For those who are already familiar with what has become a popular self-improvement genre, the ideas as building blocks might alternately be described as smart notes, permanent notes, or atomic notes. For those really into this perspective on taking notes, there are differences among these terms, but all are similar enough I am not going to get into nuances. The atomic note is perhaps the most basic of these ideas and proposes that the note taker should create exactly one note for each idea, and write it as if you’re writing so you or someone else would understand this idea in the future. Use full sentences, include references. What you get from this process over time is an accumulation of ideas (lego blocks) that you can organize in different ways to accomplish different tasks. Connections among these ideas are to be explored repeatedly over time and potential meaningful associations are to be stored with links or tags. There are two important ideas here – a) identify and store useful ideas and b) revisit your collection repeatedly overtime to identify interesting connections among these ideas.

My favorite tool for this style of notetaking is Obsidian. I might have also described Obsidian under a later heading (organization) because of the process of idea organization via links and tags, but the notion of saving isolated, but connectable concepts is so unique I decided to focus on it at this point. There are other ways to keep individual ideas both without technology (note cards), but the search and interconnection possibilities among other technology facilitated writing tools offer unique benefits over long periods of time and with a large amount of content..

Referencing

A bibliography generator is also helpful when creating a large project. Citation information from sources can be stored as the sources are being read and this makes the eventual compilation of a reference list far more efficient than attempting to assemble such a list when the project is nearing completion.

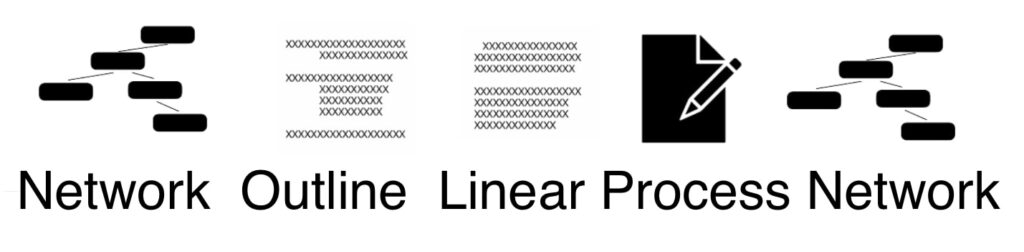

Planning – organization

Most students are familiar with outlining. Incorporating an outlining tool in a writing environment allows the writer to plan the structure of the document. Often the outline entries become headings within the document, and the writer can move back and forth between the outline view and the extended text as an aid to organizing a major project. This capability helps the writer to escape the detail level and regain a sense of the overall purpose and structure of a document which research on the writing process argues is a unique challenge. It helps the writer answer questions such as “Do I want to discuss this issue at this point or would it be better to address it at a later point?” It is also possible to reverse this process – write first and outline later. This is a way to examine the structure of what has been written with the potential outcome of moving content around to provide a more logical structure. Again, I note at this point that Google docs and Microsoft 365 will generate an outline based on the structure of headings that have been used in a document. This outline is quite useful when working with a long document to quickly locate segments you want to edit or adding some new content you have just discovered, but examining the structure of the outline is also helpful.

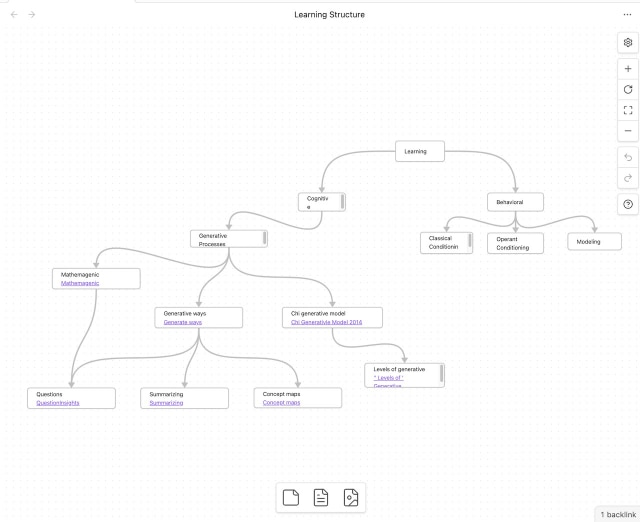

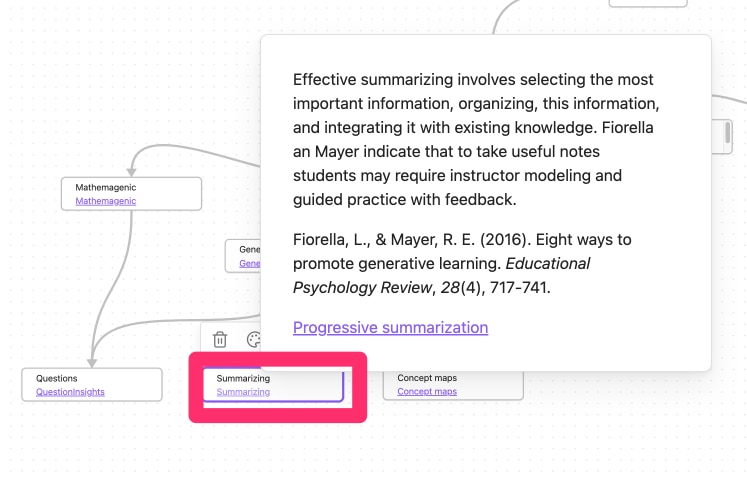

A tool often serving a similar function allows the writer to create what are called either concept or mind maps. A map consists of nodes representing ideas and links joining the nodes. As a college student, you may have encountered textbooks in which the author or authors incorporated concept maps to represent the organization of core ideas within each chapter. The idea was to help you understand the big picture by isolating the core ideas and to show how the core ideas are related. In this case, the map was intended to help you see the structure around which much additional information was probably organized. A concept mapping tool can provide a related benefit to an individual or group attempting to organize ideas for a project. The reader and writer both benefit from a well articulated structure; the reader in interpreting the product and the writer in creating the product.

The map including concepts (nodes) and a system of organization (links) need not be completed simultaneously. In a technique such as brainstorming, an individual or small group might first quickly throw out ideas that are represented as key terms or nodes. The concepts represented by the nodes might then be discussed, prioritized (some might be deleted), and structured (linked). Much in the way an outline identifies topics and subtopics, additional nodes might then be added and linked to specify details.

Translation and Editing – tools supporting content generation and simultaneous correction of writing errors.

Applications used in translation often incorporate tools to ease and correct the process. Such tools can check spelling, suggest appropriate words (dictionary, thesaurus), and identify faulty grammar. The editorial tools may signal suggestions automatically (e.g., misspelled words are underlined) or offer suggestions when assistance is requested. Grammarly is a great tool for identifying surface level errors. This may be the perfect example of a productivity tactic that simply could not be implemented when writing without technology. Even the free version of Grammarly will alert a writer to spelling, punctuation, and grammatical errors and the paid version will both identify and make improvements. Grammarly implements these capabilities using AI and as with any AI use, it is important to consider whether AI limits the practice or development of an important skill. More on this topic at a later point

Tools that allow voice input would also fall within the translation category. While most of us have probably used voice input when engaged in tasks we would probably not define as writing (asking a question through the Amazon Echo or Apple Siri, requesting a search through Google, sending a text that serves as a note while driving), text input is available as a way to generate the initial input when engaged in more traditional writing activities. It is a different experience and messy, but it is worth exploring.

Reviewing

My comments when describing the components of the writing process model differentiated editing and revision with the primary distinction being what I would describe as depth – surface (e.g., spelling, grammar) and deep (e.g, organization and logic) and the time of changes made either delayed or immediately. Often the delay allows input from other individuals with perhaps the input from others more likely to encourage structural or logical improvements.

Reviewing – sharing

Sharing a draft allows the generation of feedback from someone other than the author. While this can be accomplished in many ways, the opportunities we want to identify here allow multiple individuals to access an online file. Depending on the service, the “editor” might then download the file for commenting or interact with the file online. Sharing printed copies has long been a possibility, but digital products allow greater convenience and a higher level of interactivity.

Reviewing – commenting

Some digital writing environments allow the author to specify constraints (permissions) that control the extent to which a reviewer can interact with the shared document. For example, the author might allow read only access, commenting (comments are not actual modifications of the existing text), or modification of the text (sometimes as suggestions that be accepted or rejected). Read only access would require that the editor provide feedback separated from the original document; e.g., comments in an email. Comments might be added as text or sometimes audio that is linked to specific locations in the original document, but are available to the author in a sidebar. Finally, actual modification of the text may be possible. Such modifications might involve the embedding of suggestions in the text. When I do this for my students, I usually change font color so the author can easily identify my recommendations. The most advanced systems even combine comments and suggestions. An editor can change the original document and offer a comment to explain the modification. The author can then review these comments and decide either to accept or reject each suggested change. Accepting a suggested change modifies the document. Rejecting a change returns the document to the state that existed before editing. Reviewing a suggested change even when rejected may encourage the author to generate a change more to the author’s liking. Note that the options we describe here are not available in all writing environments, but are also not hypothetical possibilities

Educators must consider how best to support the writer. For example, the educator may prefer to rely on comments rather than suggested revisions if it becomes obvious that the author is simply accepting everything the teacher proposes as an improvement rather than using the suggestions to guide rewriting.

AI facilitated writing

While I have already hinted at ways in which AI can be applied, this mentions have involved tools integrating AI in a limited way. You can turn this relationship around and allow the writer to control general AI services to perform a wide range of writing tasks and subtasks. What many educators most fear is that learners who need to develop writing skills or demonstrate their understanding of a topic through a writing assignment will simply turn over the task to AI with the engagement the teacher intended.

Such concerns are warranted. Early on (meaning a couple of years ago), I wanted to test how far I could push a general AI tool by seeing if I could get the tool to write an Introduction to Psychology textbook. I would describe the approach I took as AI first in which I worked through a process of steps I would take, but asked the AI tool to perform a step and then I evaluated and modified the effort produced. So, what are the topics or chapters that should appear in this type of textbook? Create an outline for the chapter on learning. Using the topics identified as behavioral theories of learning, expand these topics to explain each topic to the length of a typical college textbook and at that level off complexity. No one would be fooled by what was produced, but this was some time ago and with some work a product could be produced.

I am not advocating anything like this, but I do think I gained some insight from the process. To some extent, there were hints of the Writing Process components in what I was doing. Asking for an outline of topics I could consider was an alternative to my planning a structure on my own. My personal expertise does not extend to all of the topics covered by a survey course so asking for an outline for each chapter would likely identify topics I had not considered and would need to spend time investigating to guide what I might write in these areas. I did not ask for a review and edit of what I had AI generate for the samples I had AI create, but I have since explored how AI might be applied to perform such functions.

Perhaps my present position on AI would be to explore the role AI could play in performing or facilitating the performance of specific components of the writing process. I think it reasonable to investigate how I might work collaboratively with AI in performing these different processes. This seems different from recommending that AI should substitute for learning to perform these processes or maybe it could be imagined as a way to use AI to perform certain processes when a learner focuses on performing other processes.

Reference

Bangert-Drowns, R. (1993). The word processor as an instructional tool: A meta-analysis of word processing in writing instruction. Review of Educational Research, 63 (1), 69–93.

24 total views

You must be logged in to post a comment.