While a research assistant at Cornell, Walter Pauk was credited with the development of the Cornell Note-taking system. Cornell notes became widely known through Pauk’s popular book “How to study in college” first published in 1962 and available through multiple editions. I checked and Amazon still carries the text.

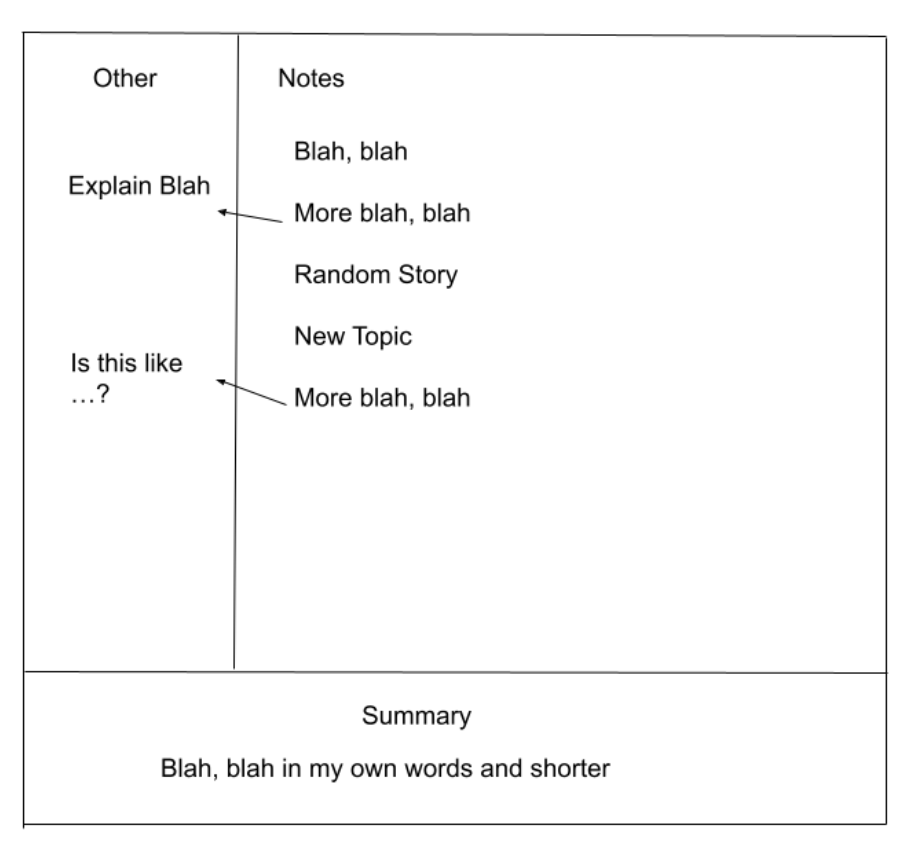

Pauk’s approach which can be applied within a traditional notebook involves dividing a page into two columns with the right-hand column about twice as wide as the left-hand column and leaving a space across the bottom of each page for writing a summary. The idea is to take notes during a presentation in the right-hand column and later follow-up in the left-hand (often called cue column) with questions and other related comments. This second pass is supposed to follow soon after class so that other memories of the presentation are still fresh. The summary section provides a space to add just what it says – a summary of the main ideas.

Paul explained the proper way to use his system as the five Rs of note-taking. In my experience, the 5 Rs are far less well-known and yet important because they explain how the basic system is to be used. I would organize and explain the 5 Rs as follows.

During class – Record

After class – Reduce

Over time

Recite (cover notes and see what you can recall based on cues)

Reflect (add your own ideas, extensions)

Review (review all notes each week)

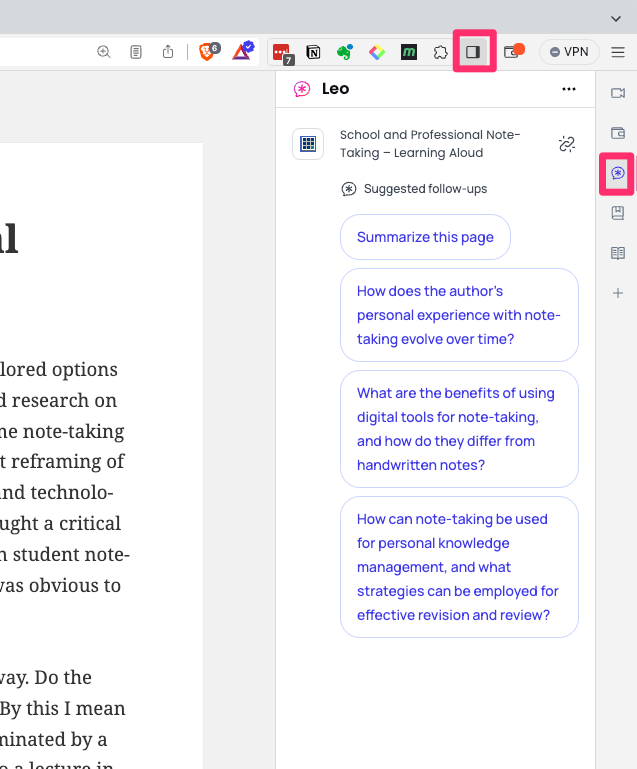

While the Cornell system was designed during a different time and was suited to the technology of the day (paper and pencil), those who promote digital note-taking tools offer suggestions for applying the Cornell structure within the digital environment of the tool they promote.

When I used to lecture about study skills and study behavior, I explained the Cornell system, but I would preface my presentation with the following questions. How many of you have heard of Cornell Notes? The SQ3R system? More had heard of Cornett notes and a few of SQ3R. I would then ask are any of you now using either of these systems to study my presentations or your textbook. In the thousands of students I asked, I don’t remember anyone ever raising her or his hand. To test my approach, I also asked if any student made and study note cards in their classes. The positive responses here were much more frequent. I tried to get a sense of why without much luck. I think my data are accurate and I raise this experience to get you to consider this same question. Students take notes, but don’t have a system.

I think Cornell notes are frequently proposed and taught to younger learners because the design of the note collection environment is simple and easy to describe. I wonder about how the process is communicated and perhaps more importantly implemented. The structure makes less sense if students are only intending to cram rather than frequently review. Does the learner have to “buy in” to the logic or do learners understand the logic, but just are not motivated to put in the effort? How any method is taught and understood likely has at least some impact on whether suggestions are implemented.

Understanding Cornell Notes at a deeper level

Note-taking has always been a personal interest and my posts have frequently commented on note-taking. I may have mentioned Cornell notes in a few of these posts, but my focus tends to be on a more basic level. If I am describing a system, what about specific components of that system have known cognitive benefits to learners?

I come to the interpretations of those advocating specific study strategies from a cognitive perspective trying to analyze those strategies from this perspective. I ask what about a given study strategy seems like it makes sense given what those who study human cognition have found that benefits learning, retention, and transfer (application). What in a given study strategy could be augmented or given additional emphasis based on principles proposed by cognitive researchers? I will now try to apply this strategy to Cornell notes. I don’t know enough about Pauk’s work to know his theoretical perspective when creating this approach. For the most part, the perspective I take in my analysis has followed Pauk’s work which occurred during the 1950s. Timelines in this regard do not require that research precede practice, but there is a possibility that new research may offer new suggestions,

Topics

My comments will be organized as three topics.

- Stages of study behavior – how should the activities intended to benefit learning occur over time. What should be done when?

- Generative experiences and a hierarchy of such experiences – My explanation of a generative activity is an external activity intended to encourage a productive cognitive behavior. By hierarchy, I am pointing to research that has attempted to identify more and less effective generative activities and explain what factors are responsible for this ranking.

- Retrieval practice / testing effect – Research demonstrates that activities requiring the recall of stored information increases the probably of future recall and also increases understanding. Testing – free recall, cued recall, and recognition tasks – are common, but not the only or necessarily the most effective ways to engage retrieval effort.

Stages of study behavior

My personal interest in note-taking can be traced to the insights of Di Vesta and Gray. These researchers actually differentiated functions – encoding and external storage, but these processes were really centered within the stages of taking notes and then review. Encoding interpreted more broadly can occur at multiple points in time and this is my point in recognizing stages.

Pauk clearly recognized stages of study in proposing that learners function according to the 5Rs. The original notes were to be interpreted, augmented, and reviewed several times between the original recording and the immediate preparation for use.

Luo and colleagues proposed that notetaking should be imagined as a three-stage process with a revision or update stage recognized after notetaking and before final preparation for use. In addition to recognizing the importance of following up to improve the original record, these researchers advocated for collaboration with a partner. Students do not take complete notes and the opportunity to compare notes taken with others allows for improvements. Research included in the paper points to the percentage of important ideas missed in the notes most record. The authors propose that lectures pause during presentations to provide an opportunity for comparison.

This source describes studies with college students using this pause and update method. Students were given two colored pens so additions could be identified. The pause and improve condition generated a significant achievement advantage (second study). However, this study found no benefit when comparing taking notes with a partner vs alone. Researchers looked at notes added and found few elaborations.

In an even more recent focus on multiple stages as part of a model for building a second brain, Forte described a process called distillation or progressive summarization. In this process focused on taking notes from written sources, original content is read using an app that allows the exportation of the highlighted material. This content is first bolded and then highlighted to identify key information (progressive distillation). A summary can then be added. The unique advantage in this approach is to keep all of the layers available. One can function at different levels from the same immediate source and backtrack to a more complete level should it become necessary to recall a broader context or to take what was originally created in a different direction.

It is possible to draw parallels here between what the Cornell system allows and what Forte proposes. The capability of reinstating context and addressing information missing from the original notes is also an advantage of the digital recording of an audio input keyed to specific notes as they are taken (see SoundNote).

Di Vesta, F. & Gray, S. G. (1972). Listening and note taking. _Journal of Educational Psychology, 63_(1), 8-14.

Forte, T. (2022). Building a second brain: A proven method to organize your digital life and unlock your creative potential. Atria Books.

Luo, L., Kiewra, K. A., & Samuelson, L. (2016). Revising lecture notes: How revision, pauses, and partners affect note taking and achievement. Instructional Science, 44(1), 45-67.

Hierarchy of generative tasks

Again, a generative experience is an external activity intended to encourage productive activities. These productive activities may occur without any external tasks and this would be best situation because there is overhead in implementing the external tasks. However, for many learners and for most under some situations, the external tasks require cognitive activities that may be avoided or remain unrecognized as a function of poor metacognition or lack of motivation.

Many tasks initiated by a learner or educator can function as a generative function. Fiorella and Mayer (2016) have identified a list of eight general categories most educators can probably turn into specific tasks. These categories include:

- Summarizing

- Mapping

- Drawing

- Imagining

- Self-Testing

- Self-Explaining

- Teaching

- Enacting

Immediately, summarization can be identified from this list as being included in the Cornell system. Self-testing would also be involved in the way Pauk described recitation.

What I mean by a hierarchy as applied to generative activities is that some activities are typically more effective than others.

Chi offers a framework – active-constructive-interactive – to differentiate learning activities in terms of observable overt activities and underlying learning processes. Each stage in the framework assumes the integration of the earlier stage and is assumed more productive than the earlier stage.

Active – doing something physical that can be observed. Highlighting would be another example.

Constructive – creating a **product** that extends the input based on **what is already known**. For example, summarization.

Interactive – involves interaction with another person – expert/learner, peers – to produce a product.

One insight from this scheme is that there is a stage beyond what might seem to be the upper limit of the Cornell structure (i.e., summarization). I am tempted to describe this additional level as application or perhaps elaboration. Both terms to me imply using information.

Chi, M. T. (2009). Active?constructive?interactive: A conceptual framework for differentiating learning activities. Topics in cognitive science, 1(1), 73-105.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. (2016). Eight Ways to Promote Generative Learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 717-741.

Retrieval Practice

Retrieval practice is a learning technique that involves trying to recall information from memory (see also Roediger & Karpicke). There are several reasons why retrieval practice improves future retrieval, but also understanding. First, it forces learners to actively engage with the material. This helps to create stronger connections between the information and existing knowledge. I think of retrieval as looking externally into memory to try to find something connected to what I am searching to find. This makes sense if you understand memory as a web of connections among ideas. The efforts to find specific information results in the activation and awareness of other information in order to find a connection to what is desired.Exploring retrieval not only increases the strength of connection to the desired information, but also an exploration of potentially related information resulting in new insights.

Second, retrieval practice provides feedback on what has been learned and what needs more attention. This helps learners to identify areas where they need to improve.

Retrieval practice is sometimes called the testing effect and asking questions or being asked questions is one way to trigger the search process (e.g., Yang and colleagues), Self testing is an activity embedded in the way Pauk imagines the use of Cornell notes. I am guessing it is also a reason the strategy of making and using flash cards is such a common study strategy.

There are however other ways to practice retrieval. Yang and colleagues speculate that retrieval practice plays in role in the proven benefits of a learner teaching and preparing to teach. Teaching represents an important link here to the more productive levels of generative learning (see previous section). The previously mentioned hierarchy attributed to Luo and colleagues recognized the value of collaboration in reviewing notes and again the addition of sharing and discussion would represent important extensions of a personal use of any note-taking system.

Koh, A. W. L., Lee, S. C., & Lim, S. W. H. (2018). The learning benefits of teaching: A retrieval practice hypothesis. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 32(3), 401-410.

Luo, L., Kiewra, K. A., & Samuelson, L. (2016). Revising lecture notes: How revision, pauses, and partners affect note taking and achievement. Instructional Science, 44(1), 45-67.

Roediger III, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). The power of testing memory: Basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspectives on psychological science, 1(3), 181-210.

Yang, C., Luo, L., Vadillo, M. A., Yu, R., & Shanks, D. R. (2021). Testing (quizzing) boosts classroom learning: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(4), 399-435.

Summary – My effort here was an attempt to cross reference what might be described as a learning system (Cornell Note) with mechanisms that might expain why the system has proven value and possibly allow the recognition of similar components present in other study systems. In addition, I have tried to emphasize that the components of a system may not be understood and applied in practice. Collaboration was suggested as a way to extend the Cornell system.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.