Student access to AI has created a situation in which educators must consider when AI should and should not be used. I think about this question by considering the difference between what skill or skills are the focus of instruction and whether AI will replace a skill to improve the efficiency of the writing task or will support a specific skill in some way. It may also be useful to differentiate learning to write from writing to learn. My assumption is that unless specific skills are used by the learner those skills will not be improved. Hence when AI is simply used to complete an assignment a learner learns little about writing, but may learn something about using AI.

Writing Process Model

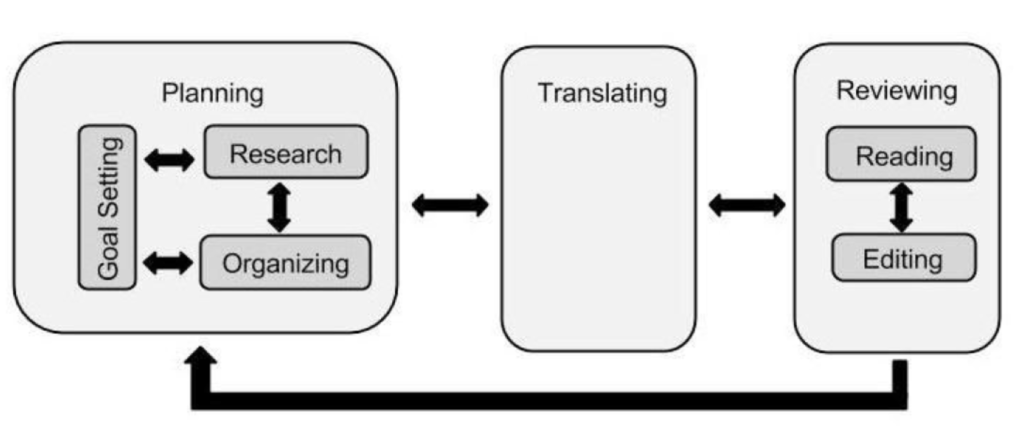

The writing process model (Flower & Hayes, 1981) is widely accepted as a way to describe the various component skills that combine to enable effective writing. This model has been used to guide both writing researchers and the development of instructional tactics. For researchers, the model is often used as a way to identify and evaluate the impact of the individual processes on the quality of the final project. For example, better writers appear to spend more time planning (e.g., Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987). For educators and instructional designers, understanding the multiple processes that contribute to effective writing and how these processes interact is useful in focusing instruction.

Here, the writing process model will be used primarily to identify the subskills to be developed as part of learning to write and writing to learn and I will offer my own brief description of this model. It is worth noting that other than composing and rewriting products, other uses of technology to improve writing and increase the frequency of writing experiences seldom receive a lot of attention (Gillespie, Graham, Kiuhara & Hebert, 2014).

The model

The model identifies three general components a) planning, b) translation, and c) reviewing.

Planning involves subskills that include setting a goal for the project, gathering information related to this goal which we will describe as research, and organizing this information so the product generated will make sense. The goal may be self-determined or the result of an assignment.

Research may involve remembering what the author knows about a topic or acquiring new information. Research should also include the identification of the characteristics of the audience. What do they already know? How should I explain things so that they will understand? Finally, the process of organization involves establishing a sequence of ideas in memory or externally to represent the intended flow of logic or ideas.

What many of us probably think of as writing is what Flower and Hayes describe as translation. Translation is the process of getting our ideas from the mind to the screen and this externalization process is typically expected to conform to conventions of expression such as spelling and grammar.

Finally, authors read what they have written and make adjustments. This review may occur at the end of a project or at the end of a sentence. In practice, authors may also call on others to offer advice rather than relying on their own review.

One additional aspect of the model that must not be overlooked is the iterative nature of writing. This is depicted in the figure presenting the model by the use of arrows. We may be tempted, even after initial examination of this model, to see writing as a mostly linear process – we think a bit and jot down a few ideas, we use these ideas to craft a draft, and we edit this draft to address grammatical problems. However, the path to a quality finished product is often more circuitous. We do more than make adjustments in spelling and grammar. As we translate our initial ideas, we may discover that we are vague on some points we thought we understood and need to do more research. We may decide that a different organizational scheme makes more sense. This reality interpreted using our tool metaphor would suggest that within a given project we seldom can be certain we have finished the use of a given tool and the opportunity to move back and forth among tools is quite valuable.

Tech tools and writing

Before I get to my focus on AI tools, it might be helpful to note that technology tools used to facilitate writing subprocesses have existed for some time. For example, spelling and grammar checkers, outline and concept mapping, note-taking and note-storage, citation managers, online writing environments allowing collaboration and commenting, and probably many other tools that improve the efficiency and effectiveness of writing and learning to write. Even the use of a computer allows advantages such as storage of digital content in a form that can easily be modified rather than the challenge of making improvements to content stored on paper. The digital alternative to paper changes how we go about the writing process. I have written about technology for maybe 20 years and one of the bextbooks offered the type of analysis I am offering here not about AI tools, but about the advantages of writing on a computer and using various digital tools.

A tool can substitute for a human process or a tool can supplement or augment a human process. This distinction is important when it comes to writing to learn and learning to write. When the process is what is to be learned, this substitution is likely to be detrimental as it allows a learner to skip needed practice. In contrast, augmentation often allows the opposite as a busy work activity or some incapability is taken care of allowing more important skills to become the focus.

Here are the types of tools I see as supporting individual writing processes.

Planning – Organization and Research

Prewriting involves developing a plan for what you want to get down on paper (or screen in this case). A writer goes about these two subprocesses in different ways. You can think or learn about a topic (research) and then organize these ideas in some way to present. Or, you can generate a structure of your ideas (organize) and then research the topics to come up with the specifics to be included in a presentation. Again, these are likely iterative processes no matter which subskill goes first.

One thing AI does very well is to propose an outline if you are able to generate a prompt describing your goals. You could then simply ask the AI service to generate something based on this outline, but this would defeat the entire purpose of learning about the topic by doing the research to translate the outline into a product or developing writing skills by expanding the outline into a narrative yourself.

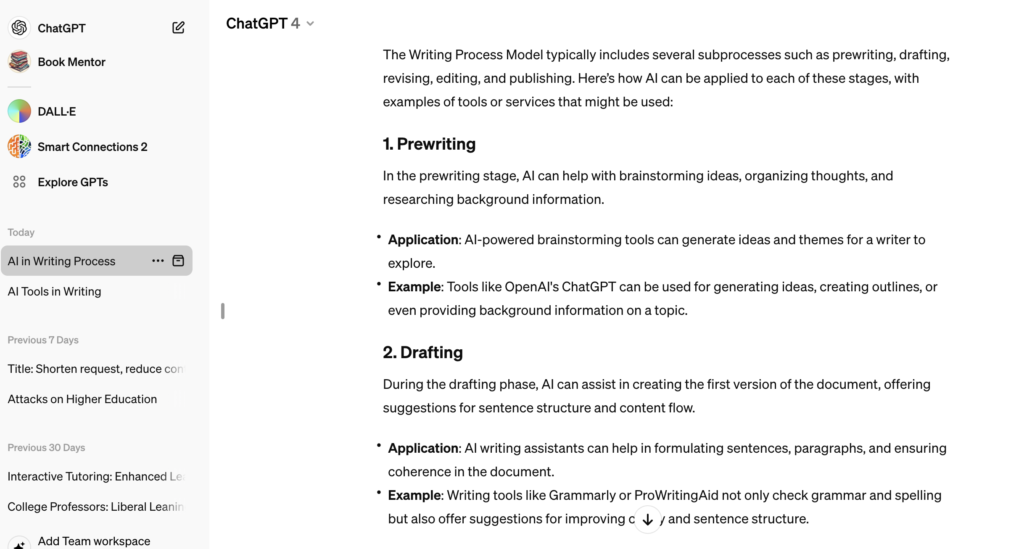

Since I am writing about how AI might perform some of the subskills identified by the writing process model, I asked ChatGPT to create an outline using the following prompt.

“Write an outline for ways in which ai can be used in writing. Base this outline on the writing subprocesses of the writing process model and include examples of AI services for the recommended activity for each outline entry.”

The following shows part of the outline ChatGPT generated. I tend to trust ChatGPT when it comes to well established content and I found the outline although a little different from the graphic I provided above to be quite credible and to offer reasonable suggestions. As a guide for writing on the topic I described, it would work well.

I had read that AI services could generate concept maps which would offer a somewhat different way to identify topics that might be included in a written product. I tried this several times using a variety of prompts with ChatGPT’s DALLE. The service did generate a concept map, but despite making several follow-up requests which ChatGPT acknowledged, I could not get the map to contain intelligible concept labels. Not helpful.

Translation

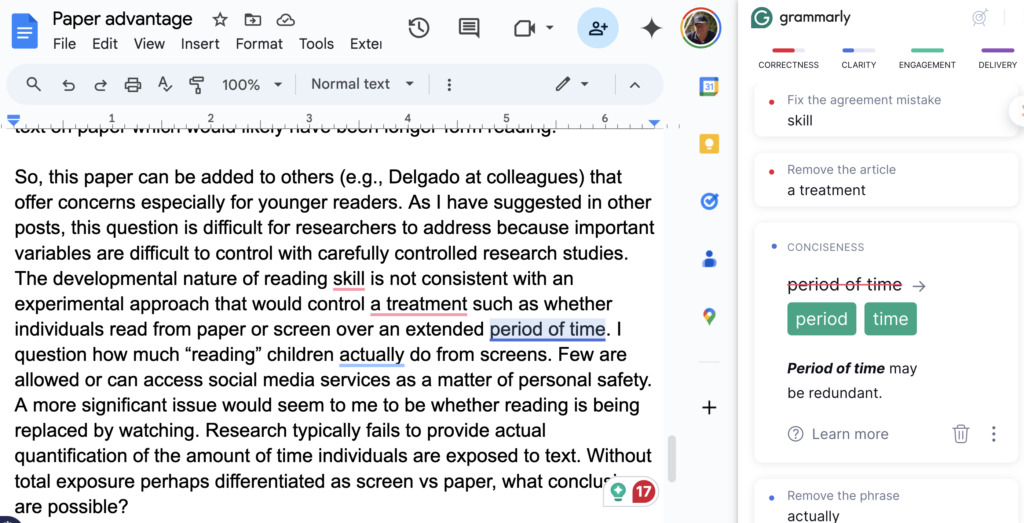

Tools for improving the translation process have existed in some form for a long time. The newest versions are quite sophisticated in providing feedback beyond basic spelling and grammatical errors. I write in Google docs and make use of the Grammarly extension.

I should note that Grammarly is adding AI features that will generate text. Within the perspective I am taking here I have some concerns about these additions. Since I am suggesting that writing subskills can be replaced or supported, student access to Grammarly could allow writing subskills the educator was intending students to perform themselves to be performed to some degree by the AI.

If you have not tried Grammarly, the tool identifies different types of modifications the tool proposes different modifications the writer might consider changing (spelling, missing or incorrect punctuation, alternate wording, etc.) and will make these modifications if the writer accepts the suggestion. The different types of recommendations are color-coded (see following image).

Revision

I am differentiating changes made while translating (editing) from changes made after translating (revision). Minor changes such as spelling and grammar would seem more frequently fixed as edits by this distinction and major modifications made (addition of examples, restructuring of sections, deletion of sections, etc.) while revising. Obviously, this is a simplistic differentiation and both types of changes occur during both stages).

I don’t know if I can confidently recommend a role for AI for this stage. Pre-AI, one might recommend that a writer share their work with a colleague and ask for suggestions. The AI version of Grammarly seems to be moving toward such capabilities. Already, a writer can ask AI to do things like shorten a document or generate a different version of a document. I might explore such capabilities out of curiosity and perhaps to see how modifications differ from my original creations, but for work that is to be submitted for evaluation of writing skill would that be something an educator would recommend?

I have also asked an AI tool to provide an outline, identify main ideas or generate a summary of a document I have written just to see what it generates. Does the response to one of these requests surprise me in some way? Sometimes. I might add headings and subheadings to identify a structure I thought was not as obvious as I had thought.

Conclusion:

My general point in this post was that questions of whether learners can use AI tools when assigned writing tasks should be considered in a more complex way. Rather than the answer being yes or no, I am recommending that learning to write and writing to learn are based on subprocesses and the AI tool question should be considered in response to a consideration of whether the learner was expected to be developing proficiency in executing a subprocess. In addition, it might be important to suggest that learning how to use AI tools could be a secondary goal.

Subprocess here were identified based on the Writing Process Model and a couple of suggestions were provided to illustrate what I mean by using a tool to drastically reduce the demands of one of the subprocesses. There are plenty of tools out there not discussed and my intention was to use these examples to get you thinking about this way of developing writing skills.

References:

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). An attainable version of high literacy: Approaches to teaching higher-order skills in reading and writing. Curriculum inquiry, 17(1), 9-30.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College composition and communication, 32(4), 365-387.

Gillespie, A., Graham, S., Kiuhara, S., & Hebert, M. (2014). High school teachers use of writing to support students’ learning: A national survey. Reading and Writing, 27, 1043-1072.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.