Functional computers (Macs, Windows, and Chromebooks) age of support by manufacturers. Companies have decided they cannot maintain safe OSs over several different hardware updates. Google has generated a Chrome OS that allows users of these older computers a way to continue to use their machines as Chromebooks.

The following tutorial explains how I have used this OS (Chrome Flex) with a couple of my older machines.

Chrome Flex has been available for a couple of months now, but I had to wait until I returned home from my winter break and had access to a couple of old computers and a flash drive. One of the few challenges to spending the winter months in Kauaii is not having access to all of my stuff.

As I understand the history, Google purchased Cloud Ready and now offers a related product, Chrome Flex, at no cost. Chrome Flex is intended to offer a solution to two problems: 1) old Macintosh and Windows computers unable to run the current operating system intended for their brand and 2) Chromebooks that have passed the date at which they are still supported. I guess this is kind of the same problem. Often these machines are still functional and the older Macs and Windows machines may have the power and storage equal to or exceeding the less expensive Chromebooks. Schools and others interested in inexpensive alternatives might repurpose older machines with an operating system that allows them to function as Chromebooks and extend the useful life of these machines before sending them to the technology dump.

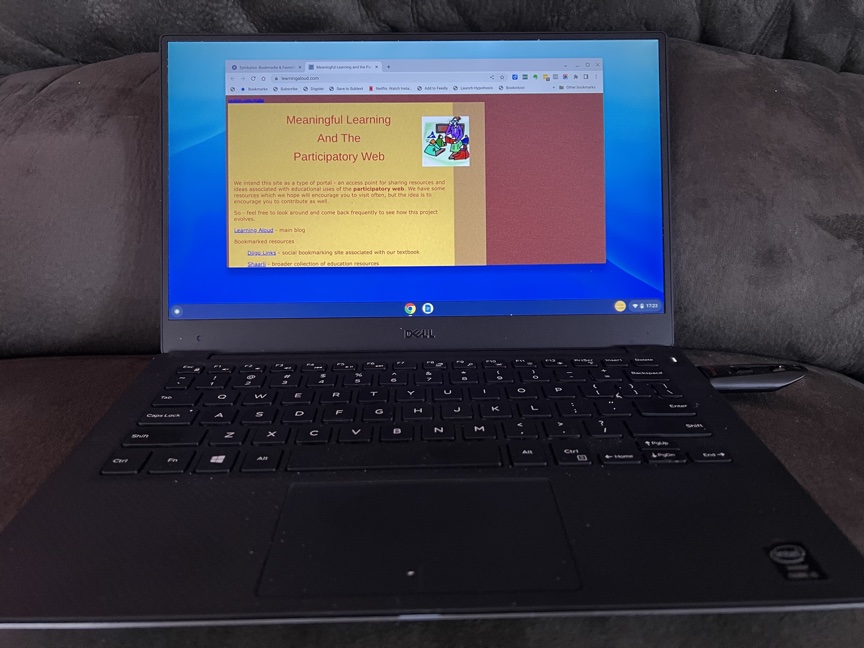

I have both an old Macbook Air and an old Dell that I have not used in years, but still keep around for experiments – usually a Linux install of some type. These machines are ideal for conversion to a Chromebook.

The process is easier than you might expect. All you need is a flash drive and an existing Chrome browser to which you add the Chromebook Recovery Utility (it is a Chrome extension). This extension allows you to create a recovery disk on the Flash Drive. Follow the instructions in creating the recovery drive and then use it with the computer you want to convert. I didn’t actually convert either of the old computers to a Chromebook – running the Chrome OS from the flash drive was good enough for me. I already have a perfectly good Chromebook, but maybe you don’t.

Two resources that will take you through the process – Android Police, HowtoGeek.

Chrome Flex worked great. This has to be one of the most successful repurposing ventures I have tried.

What I learned

1) Don’t be cheap with the flash drive. I originally tried the install with a 32GB flash drive I found in a drawer. I had trouble with crashes and getting anything beyond very basic web browsing to work and nearly gave up on the entire adventure. They don’t offer this caution in the articles I read. I purchased a 512 GB flash drive (not cheap) and everything worked without any hiccups

2) When you access the flash drive from your older computer, you can try Chrome Flex from the drive or go ahead with the installation. I have learned from experience to try an experimental OS from the install drive first. I would get Flex to work on both the Mac and Windows machine, but I encountered problems with specific drivers on the Windows machine. It would not produce audio. I have encountered exactly this same problem when attempting linux OSs – the basic apps would work, but I would have trouble with drivers. Individuals with more experience or more patience may be to get my Dell to function without limitations, but I have never had a complete success with the Dell. Try running from the Flash Drive to identify such issues,

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.