I have a personal interest in promoting to teachers the educational potential of what I have decided to describe as layering services. Perhaps layering is not the best choice of descriptors, but I think it makes sense once I explain what I mean. By layering, I mean the opportunity certain online services provide students to highlight, annotate, and add questions to online content (web pages and videos) in a way that does not violate the copyright of the content creators. For educators, layering involves these same components plus some others (e.g., discussion prompts) allowing teachers to share documents with these embellishments with students. These capabilities are of value when assigning online content or when teachers create their own content to implement instructional strategies such as flipping the classroom. Typically, different services must be used to layer websites and videos.

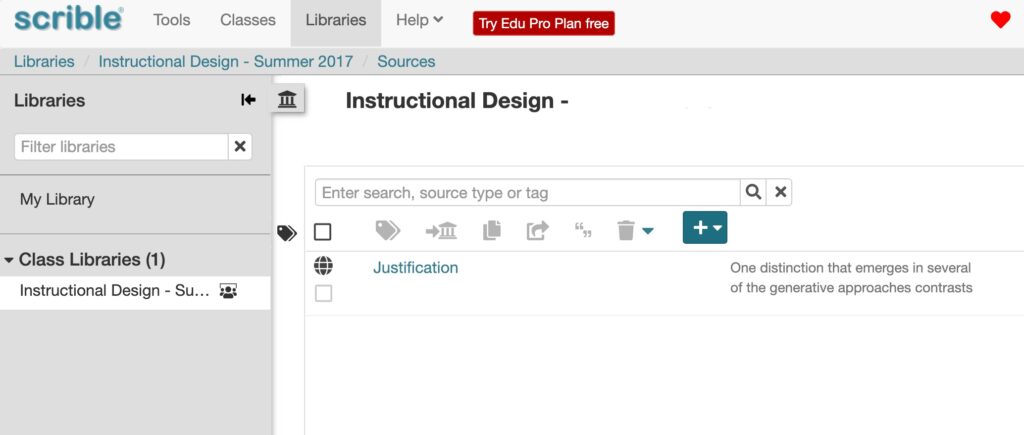

Scrible is a tool for layering web pages. I have described this service some time ago, but the service offers some new features and it is worth a review. If you want to explore Scrible use this link which takes you to the version for educators and students. Scrible is free with extra storage and a few extra features for a price.

You will note the similarity between my recent posts on tools for taking Smart Notes. Certainly, Scrible shares many of these same capabilities (highlighting and annotation, collection of layered resources into a library, sharing layered resources with others) and perhaps Scrible might be described as a Smart Note or Second Brain tool designed for students. I see some differences in this perspective and more traditional thinking about how learners can most effectively study digital texts, but many tools can be used for either purpose. The difference is mostly the time frame in question (e.g., the next test vs. the next decade), but I see the more common educational emphasis on note-taking and note studying – what types of external activities can help a learner develop understanding and improve retention and application. I think a description of how Scrible works will allow educators to see benefits of the tool in meeting either goal.

Scrible Tutorial

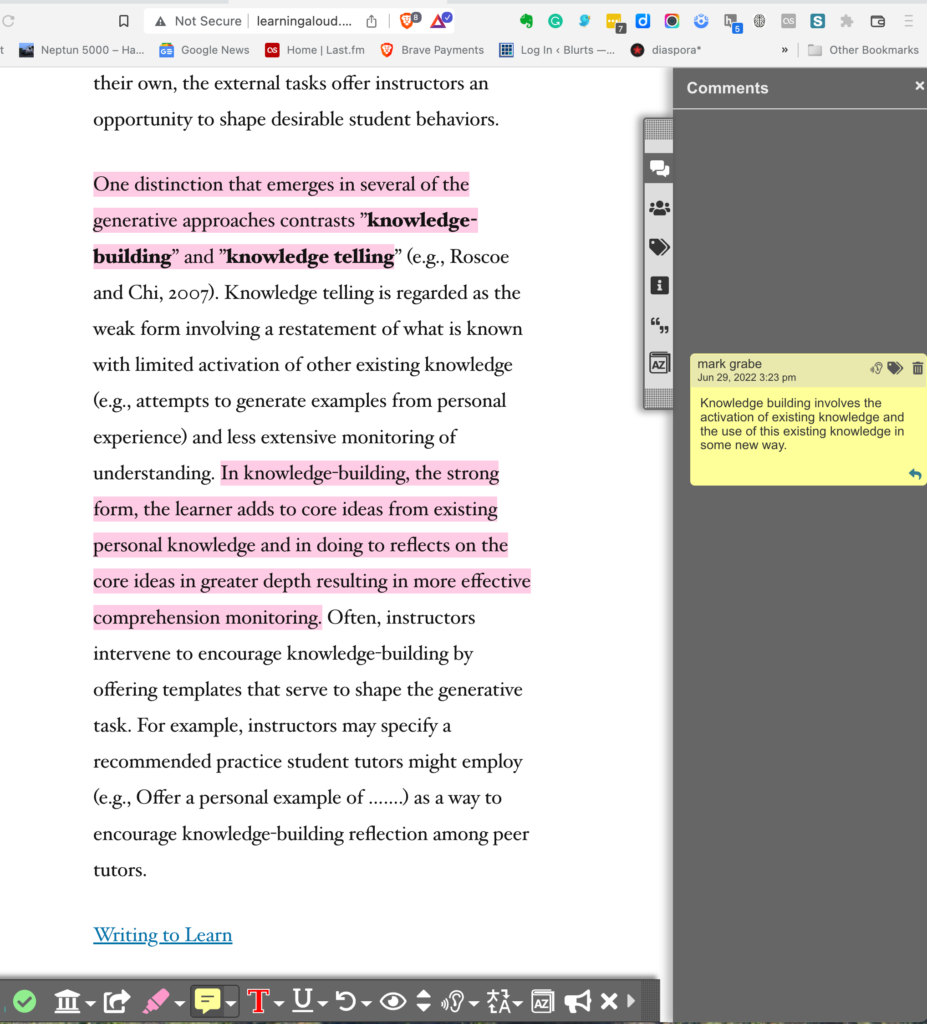

Scrible is an extension for Chrome. You use the browser to get to a page you want to study and then activate Scribe from the toolbar of the browser. The toolbar icon activates the tool tools that now appear at the bottom of the browser window and also a toolbar along the right-hand side of the browser. Here you can see I have already used the highlight tool and the note tool to create a note that appears in the Comments column.

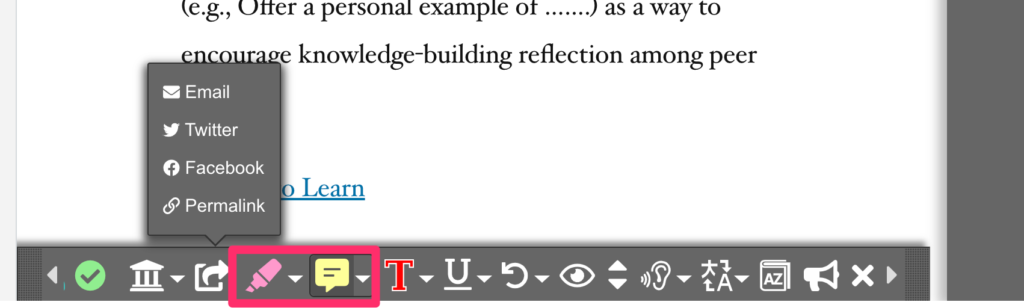

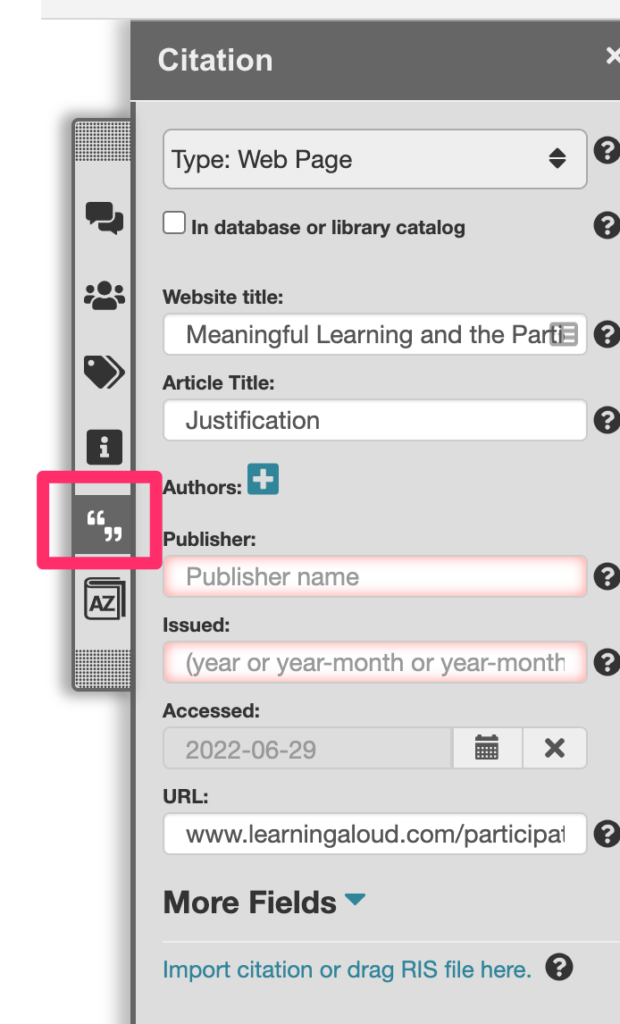

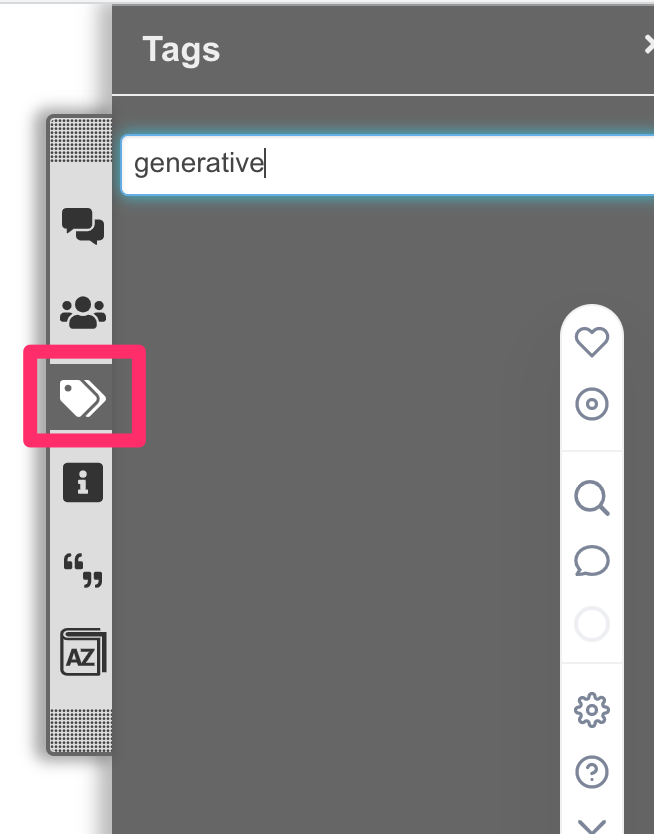

The tools on the right allow the right-hand sidebar to be used in different ways.

Storage of information about the source.

The addition of tags to the stored representation of the page.

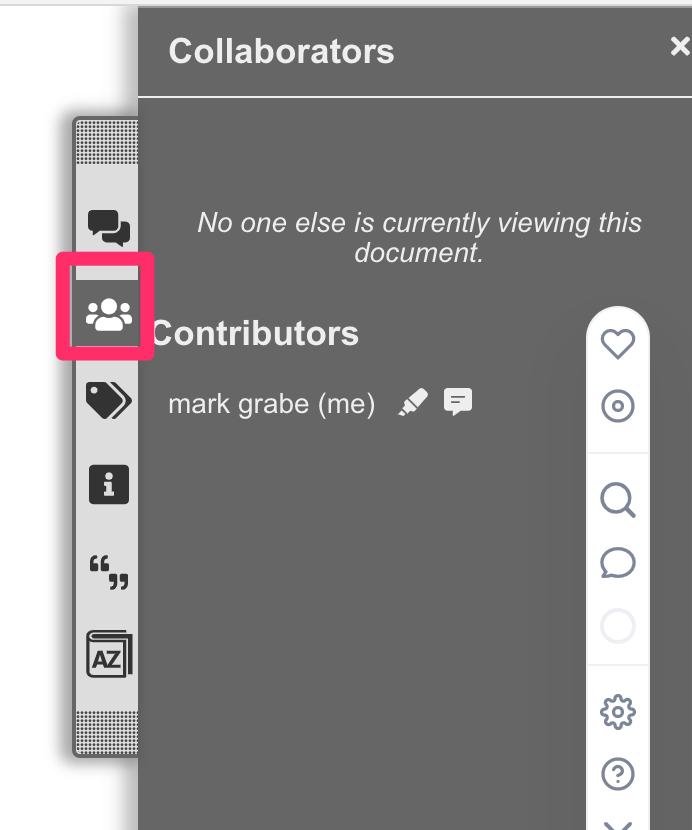

The contributors who have worked on the annotation of the page.

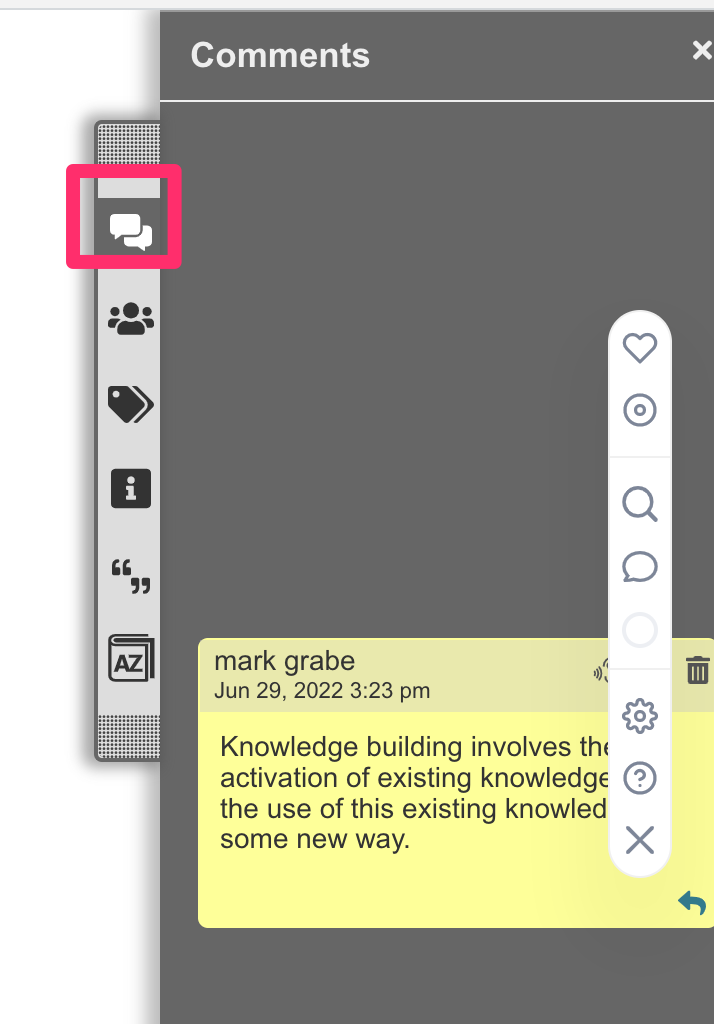

The stored comments (annotations).

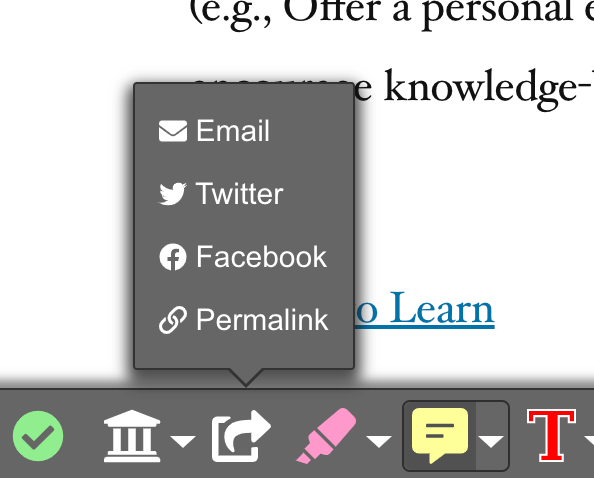

A link can be generated to share an annotation page with another user (Permalink). This link can be used to invite others users to contribute to the annotation or just to view what has been added.

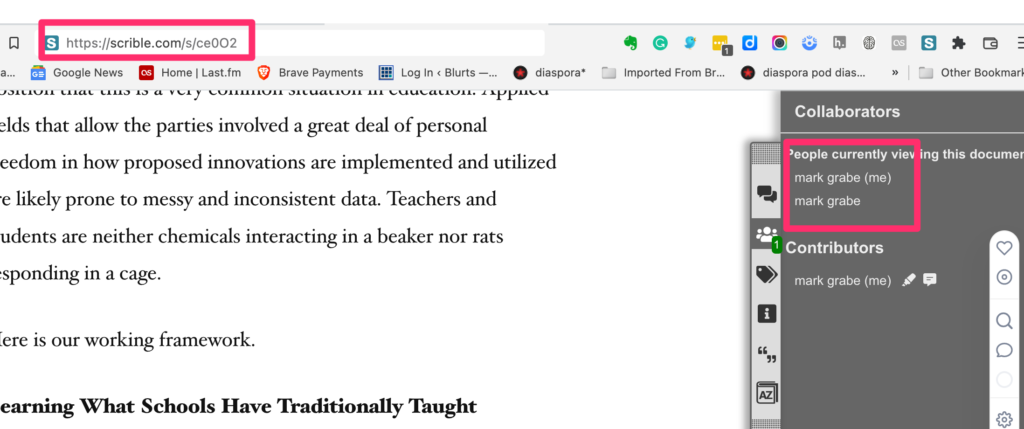

See the link to the layered annotations on the original page and the addition of a second user when this link is used by another Scrible user.

The icon next to the share icon in the bottom toolbar (the building) is used to store annotated content and access the body of stored content.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.