Little that I write comes originally from my own thoughts. Ideas mostly start with things I have read and occasionally heard. Giving credit when possible is a value I learned early.

My comments in this series are based on an analysis of my own writing process with an eye toward improvements I might make. This is not a new goal as I have experimented with aspects of this process and how I might support it with technology for years. I have explained the more immediate impetus in a previous post.

This post concerns the various tools I use to collect and process ideas from various inputs. The goal of what I am working on in my most recent process upgrade is to try to move aspects of writing earlier in this process. My intention is to use the note-taking capabilities of many of the tools that follow more aggressively and to feed these notes forward to the newest stage I will explain in the post that follows. The following material is organized by input source. You may have more of an interest in some of these inputs than others depending on how you contact information in your life,

Listening

I have included listening more based on past experiences than on present practices. I used to take notes during presentations I would attend. Often these presentations would occur at conferences I attended. If you are younger, you may be attending classes and taking notes as part of that type of formal learning environment.

The two tools I list here have an interesting capability I think most could benefit from applying. The tools record audio and link locations in the timeline of this audio to any notes that are taken. The benefit here is that should the notes be vague at later consideration, the original audio can easily be reviewed for clarification. I also suggest that when the note taker realizes that something is slipping past them they simply enter some marker in their notes – “I am confused here”.

Pear Note – http://www.usefulfruit.com/pearnote/

SoundNote – https://soundnote.com/

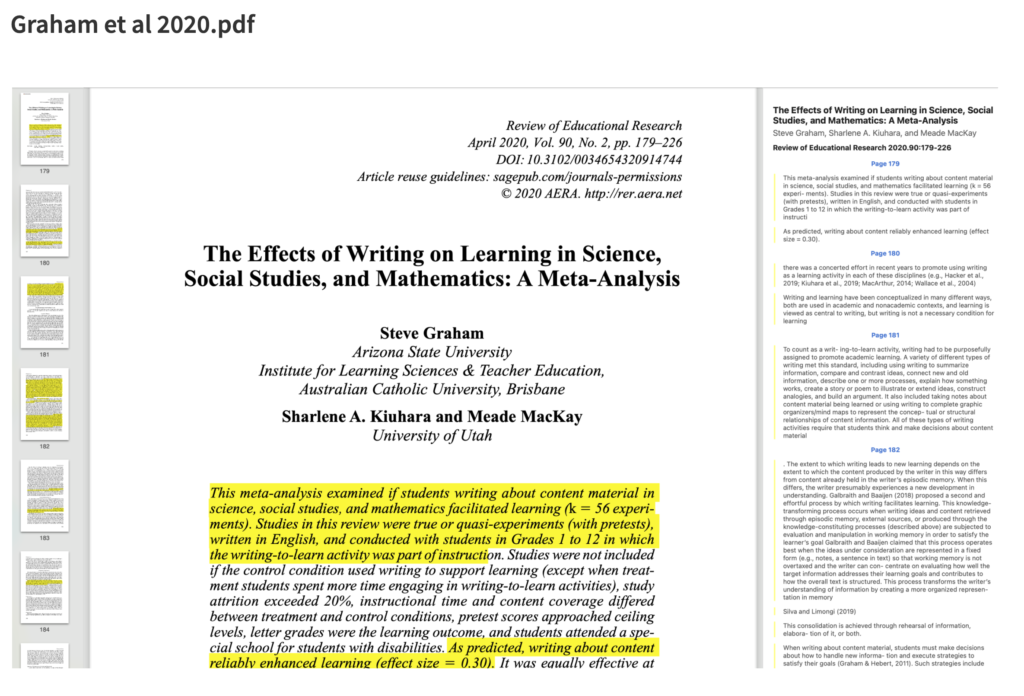

Journal Articles as PDFs

I am a retired academic so much of what I read and still write about is originally encountered in journal articles. For years now, university libraries offer online access to these journals allowing the download of the pdfs of articles. I used to joke that I would use my computer to download what I wanted to read before I would walk across my office to find the same article in a journal I had on my shelves. I used to use EndNote to read and highlight articles. I had issues synching the annotated content between my textbook computer which is the machine I prefer for writing and my iPad which is the machine I prefer for reading. After some experimentation, I settled on BookEnds and Highlights for these purposes. I use them together as each has advantages. The unique value of Highlights is that highlights and notes are easy to export as a separate document should you want to use this content separate from the original pdf (the image below is from Highlights). I believe these are primarily Apple tools and both require a subscription fee.

BookEnds – https://www.sonnysoftware.com/

Highlights – https://highlightsapp.net/features/

EndNote – https://endnote.com/

The following is the display when highlighting and annotating in Highlights. The highlighted content and notes generated appear in a separate panel on the right and can be exported.

Other pdfs

I do read other content as pdfs. My tool for this is Mendeley based in a more organized setting called the Mendeley Desktop. If you are trying to avoid paying for a service that both organizes and allows the annotation of pdfs, this would be my recommendation.

Mendeley Desktop – https://www.mendeley.com/download-reference-manager/macOS

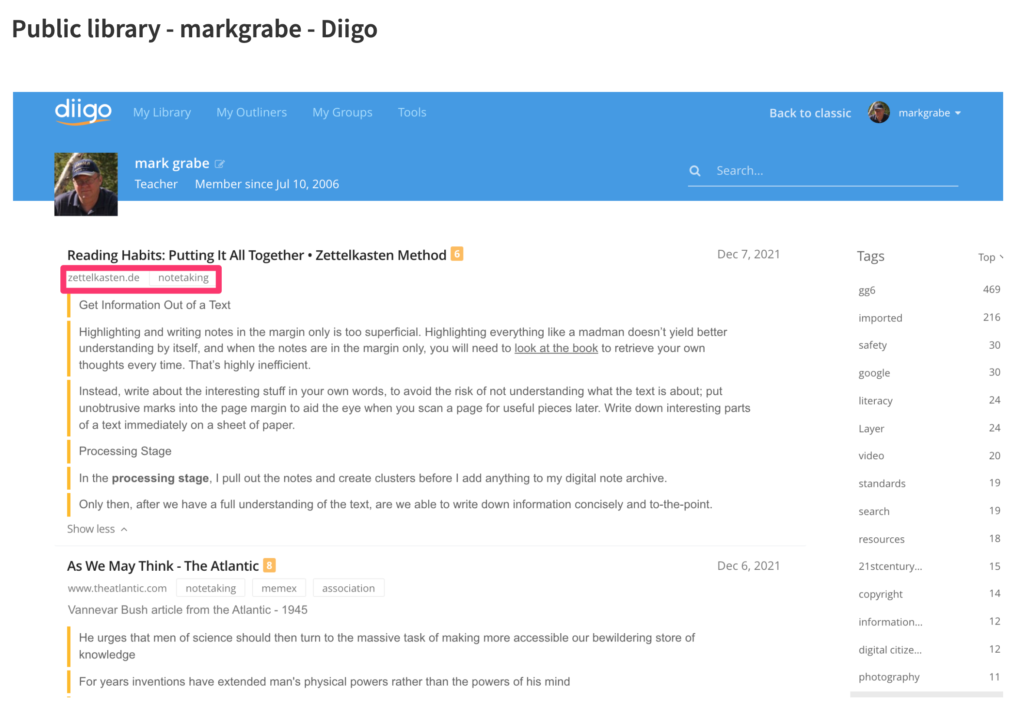

Web Content

Diigo is considered a social bookmarking tool. It is social because stored bookmarks (and contents) can be made available to others. A user can set the default to private and then uncheck a box that would add the annotations/highlights for a given site to make the content public. The bookmark itself stores the web address of the original content, Highlights and annotations are stored as part of the bookmark. Bookmarks can be tagged (see terms within the red box) and these tags can be used to search for other bookmarks within the collection. This is a powerful tool I have used for years mostly when was focused on sharing resources with others. Lately, I have become more serious about the other opportunities (e.g., an outline tool that allows the organization of content from multiple bookmark content as an intermediary stage before writing). I offer access to my public notes in one of the links I provide here. I pay an annual fee for the Pro version of this tool. I could get by with the free version (e.g., I could delete each outline I construct to stay within the number of outlines allowed at the free level), but I am pushing myself to use more of the capabilities of this service.

Diigo – https://www.diigo.com/

My public bookmarks – https://www.diigo.com/profile/markgrabe

Books (digital only)

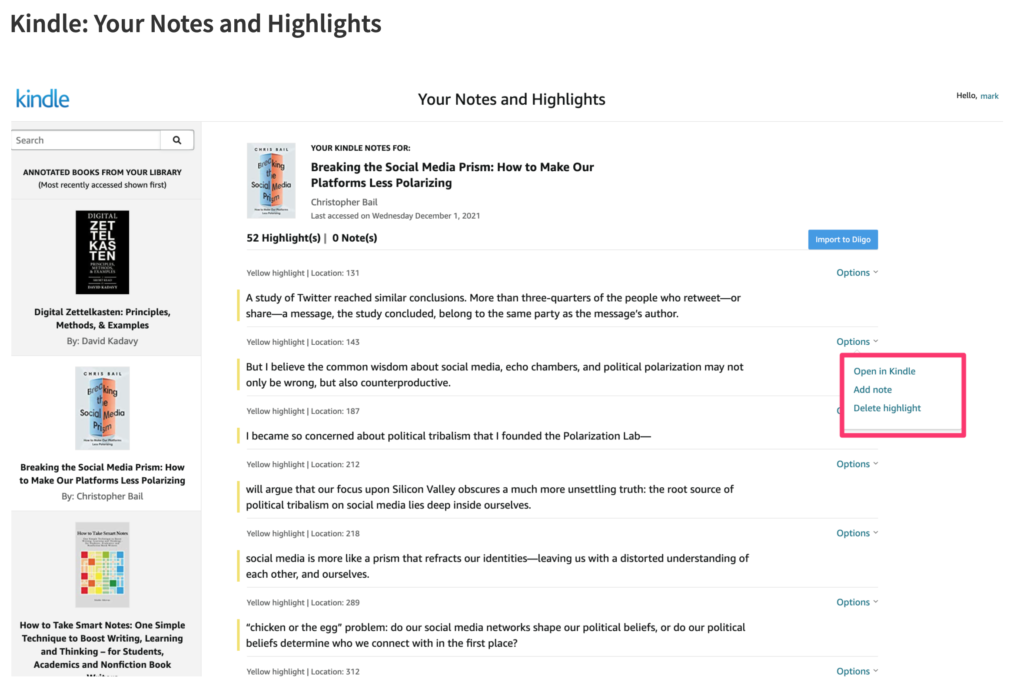

I don’t think I have purchased more than one or two physical books in the past decade and in most cases, this is because I happened to be attending a book signing. I average purchasing about a book and a half a month in digital form. I use Amazon exclusively and while I understand other similar services are available I stick to one environment as a matter of convenience.

The Kindle (on one of several devices I use) allows highlighting and note-taking. What some may not realize is that Amazon stores all of your highlights and notes online and there are several ways to access this content.

Amazon Kindle – https://www.amazon.com/b?node=16571048011

Highlights and notes generated while reading a Kindle book can be exported. This content can be found online – https://read.amazon.com/ – and can be edited further (add a note, delete the highlight) online. Kindle and Diigo have a unique relationship in that those who pay for the Diigo service can send their highlights and notes from Kindle to Diigo with the click of a button (see the blue button – Import to Diigo) in the image that appears below.

One final comment – I think it is important to give some thought to sustainability. Services come and go and the process I am attending to describe in total assumes that value comes over an extended period of time. Some issues to consider. First, are resources stored in a format that is independent of the service using the resources. Pdfs seem to meet this goal. Another format, I will discuss in the next issue is markdown text. This is essentially a text file containing common symbols to trigger things like links and tags (e.g., [[]] and #). If the worst happens and a service goes away, pdfs and markdown files can be opened using several other tools. Second, store in multiple places and backup. I try to use services that generate content I can find on a local machine and also exists with reputable services “in the cloud”. I use DropBox and iCloud for online storage. I trust these services and at worst assume I would have some warning if I would have to find a different online storage service.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.