I have been exploring many digital note-taking and annotation systems for a couple of years now. My involvement might be stretched to a decade plus if you are willing to group tools such as EndNote with this category of tools. My way of thinking about using such tools has been shaped by a career as an educational psychologist with a cognitive perspective on learning applied to topics such as note-taking, highlighting, study behavior, and generative learning activities (e.g., writing to learn, summarization, questions). This background offers some insights into what features of technology-supported learning and thinking tools might be helpful. I have gleaned a few core ideas from more recent reading – progressive summarization, smart notes that I see relevant in combination with both my newer hands-on experiences and my more general cognitive background.

What follows is a personal evaluation of the capabilities of PKM tools based on what I have just described as my personal background and experiences. I have tried to identify a title for this post. “Close, but no cigar” came to mind, but seemed too negative. I decided to go with “almost there”. What I mean by this is that I can patch together a workflow that I think works pretty well, but the system is a bit cumbersome and inefficient. I hope to offer a perspective on what an ideal tool might look like. I have based this ideal tool based on how I think Glasp should work, but so far does not.

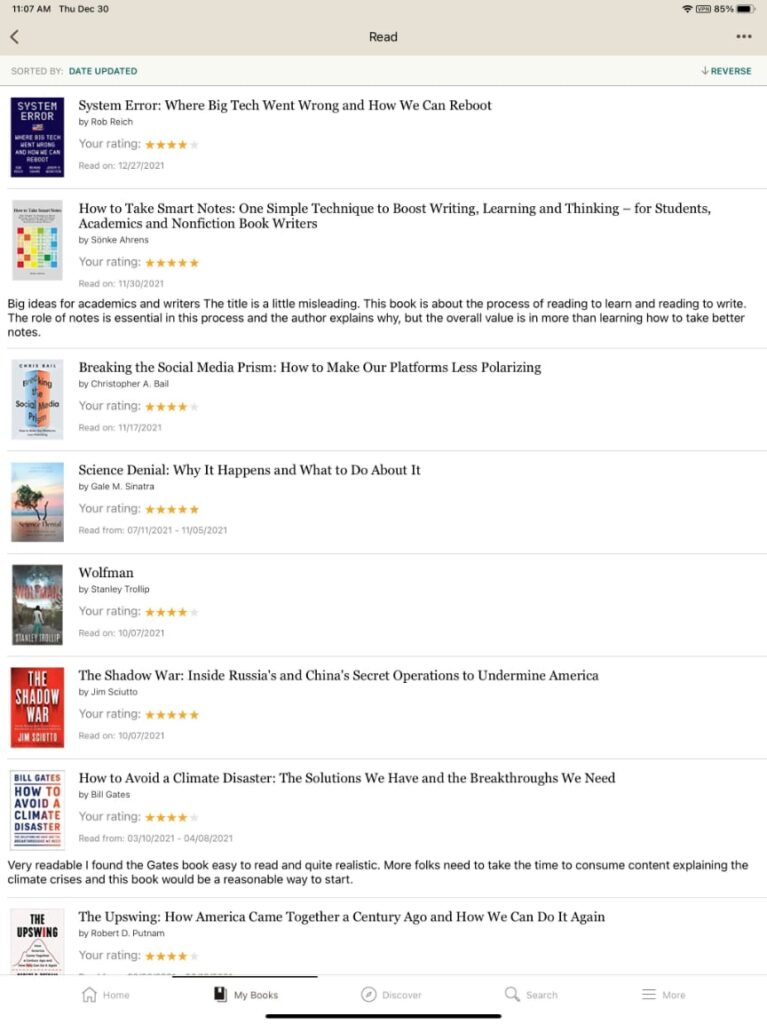

My reading activity involves web content, Kindle books, and pdfs of scientific journal articles. Ideally, all of these sources could be stored in an accessible place (I would be willing to live with a location I control – my computer or ideally personal storage online such as iCloud or DropBox). Online storage is important for both security and access from multiple devices. As I will demonstrate in my ideal approach, a common location seems to be important for the connections I see important in the system I imagine. For example, some systems do not store the pdf from which notes are taken. With the service I have in mind (Memex), I can reexamine links between the pdf and notes I have taken if I am on my own computer, but I can only see my notes if I am working on a different computer that only provides me online access. The pdf and the notes are stored in different places with the pdf on my computer and the notes in the cloud.

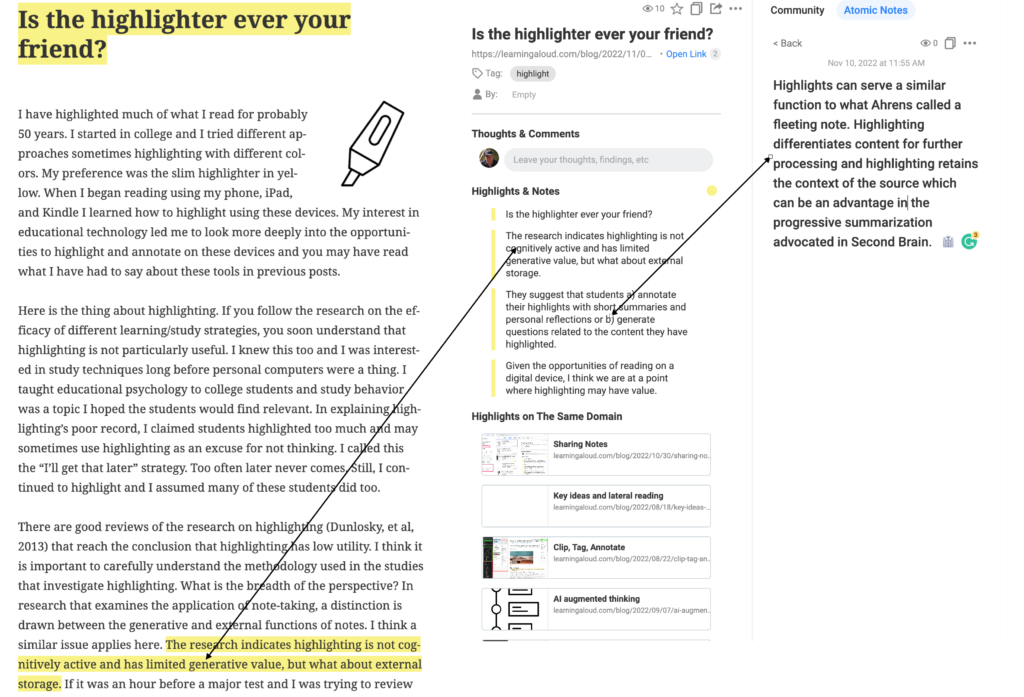

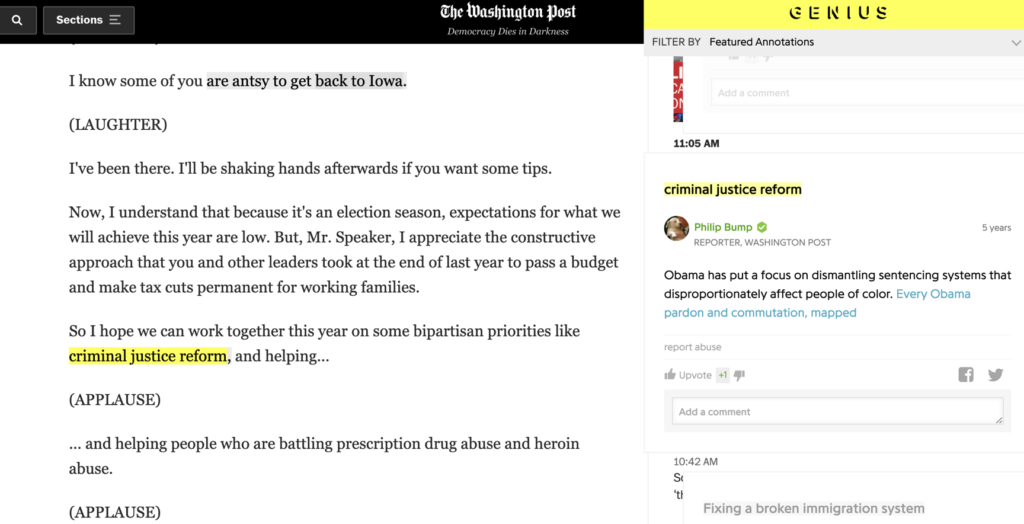

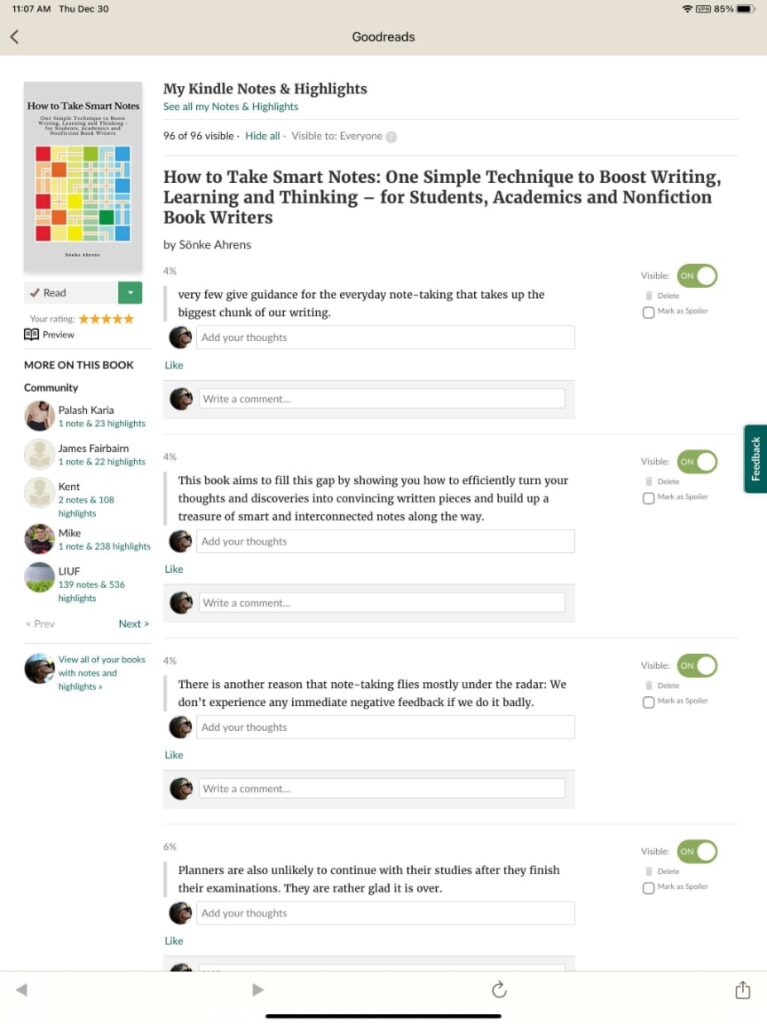

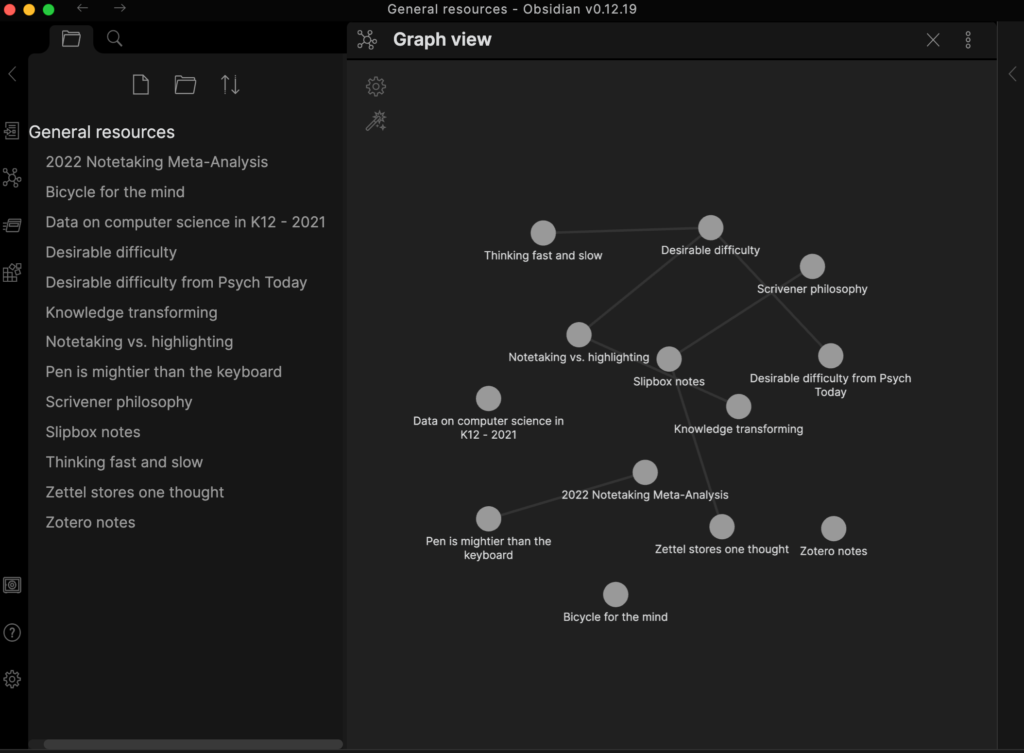

What follows is my fabricated visual description of a workflow using images from Grasp that I have merged to represent a superior fictitious system. I will be clear on what is not actually there as I proceed. The image (below) shows three panels – the leftmost panel shows original content that has been highlighted and annotated. The second panel shows isolated highlighted and notes. The third panel shows what I now label as a smart note (after Ahrens). The arrows indicate connections across panels that are bidirectional. In other words, you can get from an isolated note or highlight in the middle panel back to where in the original document this highlight exists or where the annotation/note was connected. You can get from my personally generated, standalone, summary note back to the immediate notes or highlights. These bidirectional connections are important for maintaining what might be described as context and attribution. Attribution is important in my writing to link what I write to what others have written. Context is important in establishing the broader set of information within which something I felt was important emerged. Maybe I want to seek other ideas from this same information. Maybe I just want to check on what I concluded because later my summary seems incomplete or maybe erroneous.

The system I describe allows for the generation of Smart Notes or Summary notes (I use such terms interchangeably) which capture an idea in a form that should make sense to me and someone else at a later point in time. The system allows progressive summarization in the sequence of forms getting to a smart note. Highlighting was not part of the progressive summarization process described by Forte, but I think it is fair to use it as a component in the physical transformation from the source to the personal summary I describe here.

What about these descriptions is not available? Glasp cannot be used to read pdfs. This is a serious limitation for an academic who must rely of pdfs of articles from research journals. The processing of Kindle books within Glasp allows the download of highlights and notes, but you cannot link back to the location of the selected content within the context of the original ebook. The personal summary notes (called atomic notes in Glasp) are not associated with a specific original source and you cannot get to that source through links to highlights and notes added to that source. These personal notes just accumulate as one reads different sources in this independent pane. At present, I copy and paste these notes into Obsidian and Mem X to take advantage of the organizational features of these other tools. I suppose it would be ideal if such summary notes could exist in Glasp in a way that would allow the long-term storage and manipulation of these ideas independent of source material.

To be fair to Grasp, it is still a beta service and free at this point. It is useful as is and I have found ways to integrate it with other tools to generate a reasonable workflow. Partly I wrote this post because I was contacted after writing an earlier post about Glasp and was contacted by a developer from the company. I thought I would share what I think a more complete system might look like. I hope my summary of a personal knowledge management workflow offers some insight for those unfamiliar with this expanding collection of digital tools offered to support the personal processing of source documents.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.