Smart Connections discovers and reveals related notes in Obsidian. I started using the Obsidian plugin Smart Connections because I wanted a way to apply AI interrogation of my own notes. I wanted to request cross-note summarizations and generate a variety of sample written products (e.g., blog posts) based on my personal notes and highlights. I ignored an important capability that is claimed based on the product’s name — the identification of note connections.

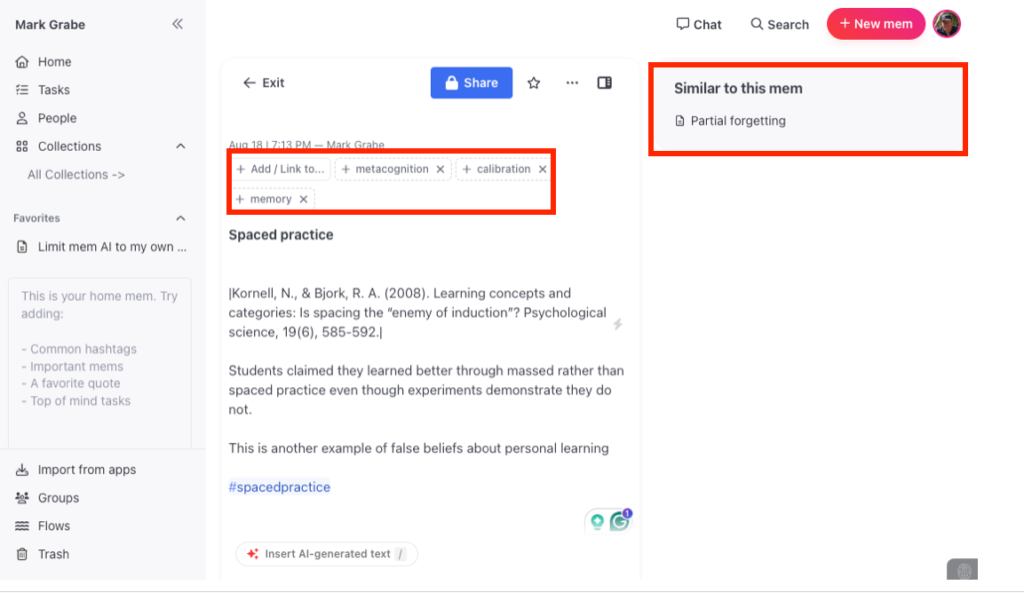

Without an AI-based method for identifying possible connections among notes, Obsidian relies on the user to establish connections via links and tags. I was aware that other services (e.g., Mem.ai) suggested that a note retention system could do better and offered tags and links, but also made the claim that AI would help surface connections. Some would argue that exploring your Obsidian content repeatedly and finding connections are important parts of the process of personal knowledge management. Constantly working with your notes is an active cognitive activity that encourages connections between what is internally retrievable at a point in time and what you are accessing in Obsidian. New connections first brain to second brain and within Obsidian may emerge. This constant interactive process is suggested by what I would describe as the Zettelkasten practitioners. I don’t think this advice must be rejected for users who want to use AI to surface new connections.

Smart Connections makes use of AI, and the AI creates a numerical representation of the content of each note and stores these as what are called embeddings. You must subscribe to an AI provider via an API, which is far less expensive than a subscription to such a service. You have the option of basing such representations on blocks within notes rather than entire notes. I make use of this option because I store lengthy notes containing book and pdf highlights, such that a representation of an entire note does not represent a level of detail that is very useful for finding something useful in such lengthy notes. In the content that follows, I will show where to turn on block embedding.

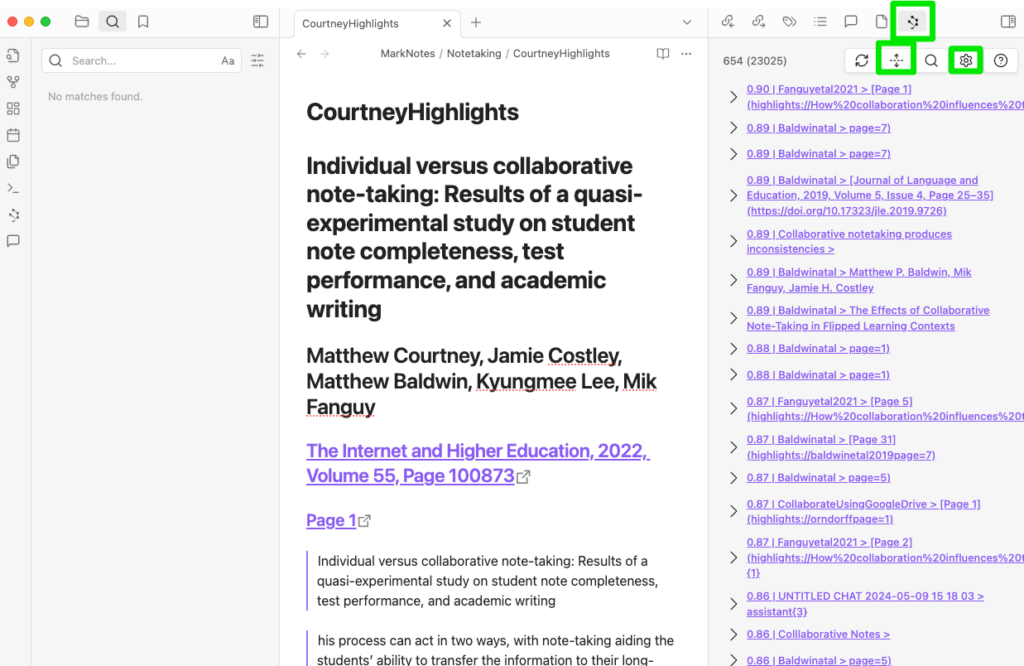

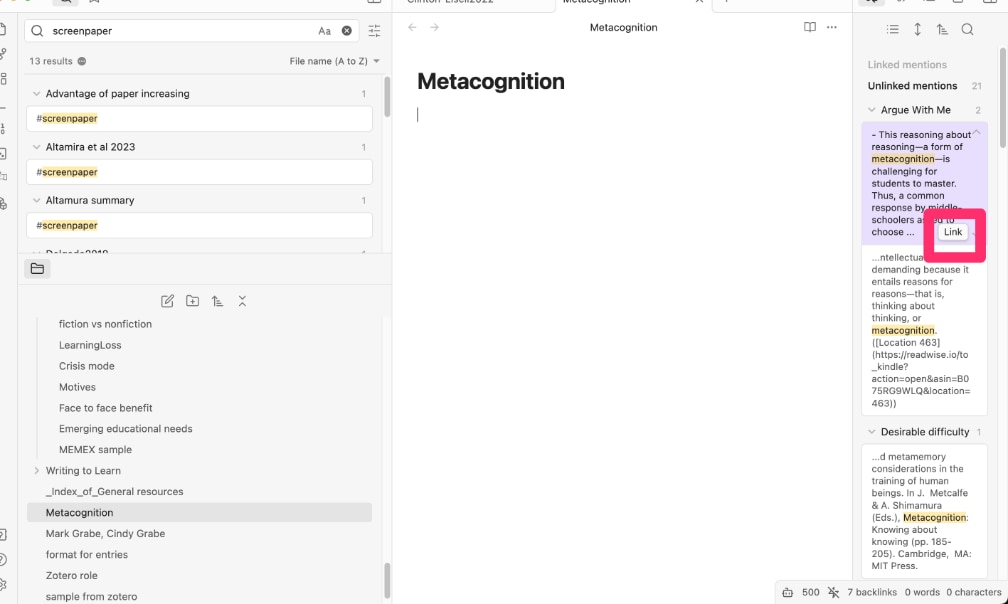

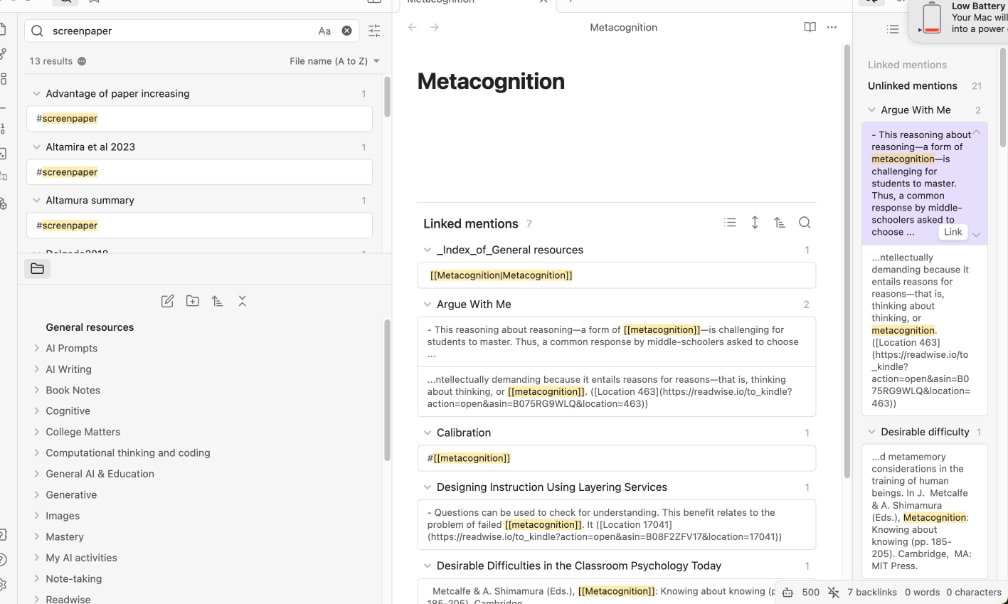

Smart Connections works by requesting connections for a note that you have selected. The following image shows Obsidian with Smart Connections active. The green rectangle in the menu bar is used to activate the Connections as opposed to the Chat capability of Smart Connections. The up/down symbol allows you to scroll through the associated notes/blocks from most related to less related. The gear symbol is used to access settings for Smart Connections. The middle panel is the active note, and the right-hand column represents a hierarchy of related notes/blocks.

Getting back to how I think AI may supplement the more hands-on use of Obsidian, I would recommend that in examining connections to a given note that you then use tags or links if you want to create permanent connections.

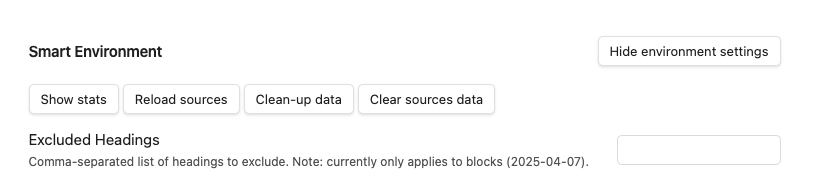

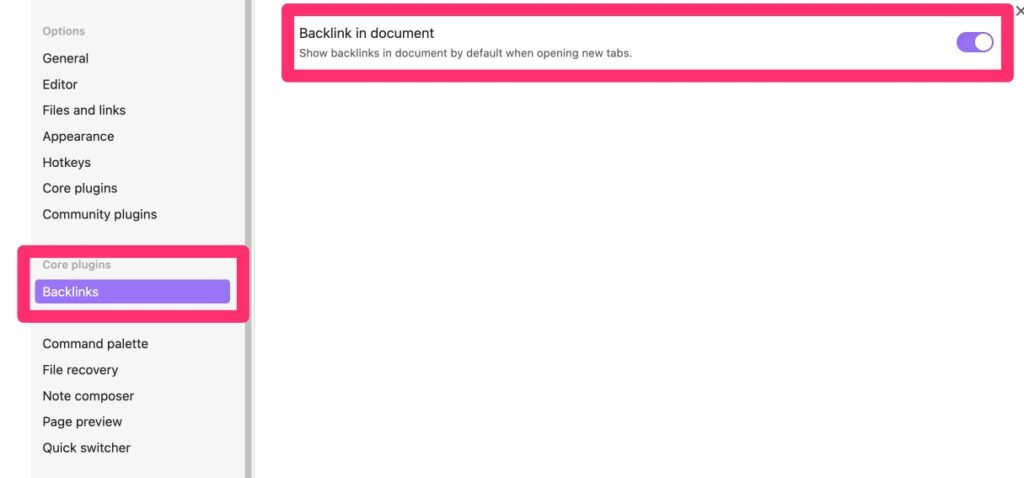

The extension of Smart Connects from note to note to note to block is worth doing if you do not keep atomic notes. Start with the Gear icon (see image above). This will reveal multiple setting options. What you are searching for are the environment settings. Open these settings with the button shown below.

Once more settings have been revealed, you are looking for Smart Blocks (see below). You turn this option on and specify a minimal length. I did not keep a careful record of the source for advice I followed and I apologize to the author, but I entered 300 characters, and that seems to work well. There are many other settings and I have mostly stayed with the defaults.

Summary:

Smart Connections is an Obsidian plugin (free) that allows AI capabilities to be applied to the notes stored in Obsidian. Chats allows a user to generate AI prompts that are applied to the contents of Obsidian. Connections generates a list of notes (note blocks in the setup I have described) associated with a selected note and is helpful in the identification of such relationships in a large collections of notes.

10 total views

You must be logged in to post a comment.