I have highlighted much of what I read for probably 50 years. I started in college, and I tried different approaches, sometimes highlighting with different colors. My preference was the slim highlighter in yellow. When I began reading using my phone, iPad, and Kindle, I learned how to highlight using these devices. My interest in educational technology led me to look more deeply into the opportunities to highlight and annotate on these devices, and you may have read what I have had to say about these tools in previous posts.

Here is the thing about highlighting. If you follow the research on the efficacy of different learning/study strategies, you soon understand that highlighting is not particularly useful. I knew this too, and I was interested in study techniques long before personal computers were a thing. I taught educational psychology to college students, and studying was a topic I hoped the students would find relevant.

There are good reviews of the research on highlighting (Dunlosky, et al, 2013) that reach the conclusion that highlighting has low utility. I think it is important to carefully understand the methodology used in the studies that investigate highlighting. What is the breadth of the perspective? In research that examines the application of note-taking, a distinction is drawn between the generative and external functions of notes. I think a similar issue applies here. The research indicates highlighting is not cognitively active and has limited generative value, but what about external storage? If it was an hour before a major test and I was trying to review the 120 pages that were assigned in my textbook, I would rather I had highlighted that book than not.

Here are some of the major findings that challenge the value of highlighting.

Highlighting may improve recall but not comprehension. (see Ponce and colleagues resource as the source for most of the comments focused on recent studies of highlighting)

Learner-generated highlighting can improve memory for the highlighted material. However, this memory boost often doesn’t extend to improved comprehension. If this distinction makes little sense, think of the difference in terms of the types of questions that might be asked to evaluate memory versus understanding. College students seem to gain more memory benefit from self-highlighting than K-12 students, potentially because they are more experienced at identifying key information. Studies focused on the importance of content that is highlighted demonstrate that college students are better at identifying core or main ideas. This makes sense for a couple of reasons. First, highlighting tends not to be encouraged among K-12 students as they use books that are not theirs. Second, college students are more experienced with the educational process and have a better feel for what content is likely to be the focus of future examinations or projects they will complete. As a consequence, and anticipating that advanced learners are likely to make use of highlighting, instruction focused on the identification of priority information is often recommended. Younger students should be asked to highlight and the type of content they designate should be evaluated.

Illusion of Mastery: Like passive rereading, looking at highlighted text can create a false sense of familiarity, leading learners to believe they know the material better than they do. This confuses familiarity with actual retrievability and understanding (Johns).

When I explored highlighting as a study technique with my students, I described a similar phenomenon. I call it the “I’ll get to that later” effect. What I proposed is that students seem to actually identify important content (these are college students), but may be challenged to understand this material. An easy way to move on and complete the reading assignment was to highlight this material, but not stop to struggle with the ideas. Later may not actually happen, or if it does, the highlighted material is then encountered out of context and less easily processed to a deeper level.

Ahrens (citations appear at the end of this post) proposes that underlining (I would assume a practice similar to highlighting) is similar to what Ahrens classifies as fleeting notes. Fleeting notes are taken to quickly capture information, and the idea of smart notes that Ahrens emphasizes focuses on the translation of fleeting notes into smart notes. A smart note can stand alone to convey meaning to the note taker and others and requires the note taker to use personal knowledge to generate a note that is meaningful now and hopefully in the future.

Highlighting of digital material may be different.

Digital reading can be different. Highlights can be exported and saved isolated from the original document. The accumulation of this once-deemed potentially useful text can be searched and examined, or potentially can become the target of an AI chat years later. This is very different than the way we highlighted journal articles or books a decade or so ago. The journals and books were stored in long rows on our office shelves, with the highlighted prose unlikely to be discovered when useful. Some books while read, were returned to the library and not highlighted in the first place.

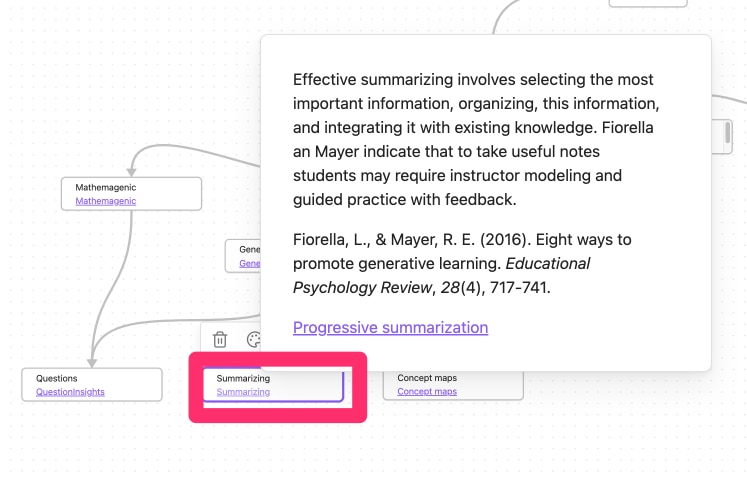

An Edutopia article on highlighting reached a negative conclusion about the value of highlighting (it may even hinder learning) and suggested solutions that educators should explain in a way very similar to that of the difference between fleeting and permanent notes. Those who are into Personal Knowledge Management methods for taking and retaining useful notes probably recognize this distinction. Ahrens suggested these terms as a way to identify important content (fleeting notes) with the expectation that this original material will receive further processing. He suggests that students a) annotate their highlights with short summaries and personal reflections or b) generate questions related to the content they have highlighted.

The Edutopia suggestions bring me to the perspective I want to emphasize.

Technology-based reading offers advantages over paper-based reading that are seldom emphasized. I rely heavily on highlighting when I write on my Kindle or using a browser extension that allows me to highlight web content. I don’t read from paper much anymore, but when I do, I also highlight a lot. When I use my iPad or computer to read and highlight, I tend to be using tools that allow me to add annotations (actually extended additions I would prefer to describe as notes) as part of the same integrated approach. I suppose I could read from a paper source and have a notebook on my desk at the same time, but I have never actually worked in this way. These highlights and notes are part of the original documents, but can also be exported for storage and further processing.

When I used to take notes from a highlighted book or journal article, it was usually later in some process of reviewing material in preparation to write something myself. In thinking about how I work now, I propose that reading using a technology-supported environment encourages the process of creating meaningful notes earlier in the process of writing, and is often disconnected from the process of creating the end product. There is an efficiency when meaningful notes are made during the initial process of reading new content in comparison to trying to create the same context when trying to make sense of highlights or notes that simply move unprocessed words from one paper source to another after a delay.

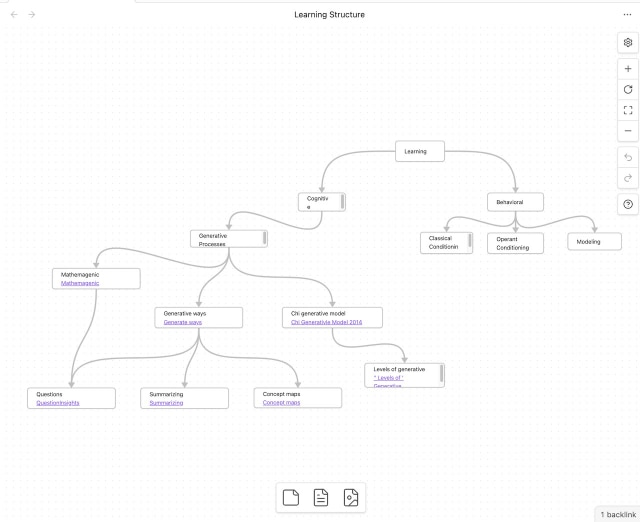

Here is my major use of the highlights from what I have read. As an academic researcher I read many, many journal articles. For the last 15 years of my career and since, I did my academic reading on the pdfs of these articles. Like other academics, I had access to these pdfs from pretty much any journal I wanted and I used these pdfs even when I owned the journals and they were on the shelf across the office from my desk. The tools I used to keep a record of the PDFs I read (originally to access the citations for articles) and to highlight these documents changed over the years, but I generated a large collection (hundreds) of highlighted articles. In recent years, I have been able to export the highlights and annotations and store this material using a personal knowledge management tool (Obsidian on my desktop and Mem.AI online). This large collection of has become a resource I can explore, link and tag. In the past couple of years, I have been able to chat with my content using AI tools (e.g., NotebookLM and Smart Connections). The opportunity being able to interact with material I have generated over decades is a very interesting experience and for someone who writes a boon to productivity,

Given the opportunities of reading on a digital device, I think we are at a point where highlighting may have value. Under these conditions, highlighting services as a placeholder for what should be a fairly immediate generation of meaningful notes. The placeholder has two benefits — it marks and saves a location in content that offers the benefit of context should a reader need to make use of the source material later. The marked material is also isolated through highlighting, and this would seem to benefit the note-making process.

One other conclusion for the Ponce and colleagues review of highlighting studies I drew from in previous sections of this post. These authors concluded that the effectiveness of highlighting was greatly enhanced when used in conjunction with more generative learning strategies, such as note-taking or creating graphic organizers. Combining highlighting with these activities showed a notably larger effect size compared to highlighting alone

I suggest it is time to prepare secondary students for these opportunities. I also argue that educators abandon the paper is best assumption. If learning is understood as a process with initial exposure not isolated from studying and review, I cannot see how paper sources have an advantage. Learn to use a digital highlighting and annotation tool and work this tool into your knowledge generation and storage workflow.

If my position makes sense to you, you may find the series of posts I have generated on note-taking to be of value.

Summary

Highlighting has often been dismissed as an effective learning strategy. Here, I argue that this is an outdated perspective based on assumptions related to the use of paper-based content. With digital content, highlighting can be an important first step in the processing of content for comprehension and value over extended periods of time.

Sources

Ahrens, S. (2017). How to take Smart Notes: One simple technique to boost writing, learning and thinking for students, academics and nonfiction book writers

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the public interest, 14(1), 4–58.

Johns, A. (2023). The science of reading: Information, media, and mind in modern America. In The Science of Reading. University of Chicago Press.

Ponce, H. R., Mayer, R. E., & Méndez, E. E. (2022). Effects of learner-generated highlighting and instructor-provided highlighting on learning from text: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 34(2), 989-1024.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.