I intend to write a couple of posts that explore issues that are related to whether content creators should serve their content themselves or rely on a service to host the content. In exploring background material for these posts, I could not help considering my own history. Strange as it may sound, I ended up trying to establish how I did what I did. Trying to establish my own behavior was a bit of a challenge as some of these personal experiences happened long ago.

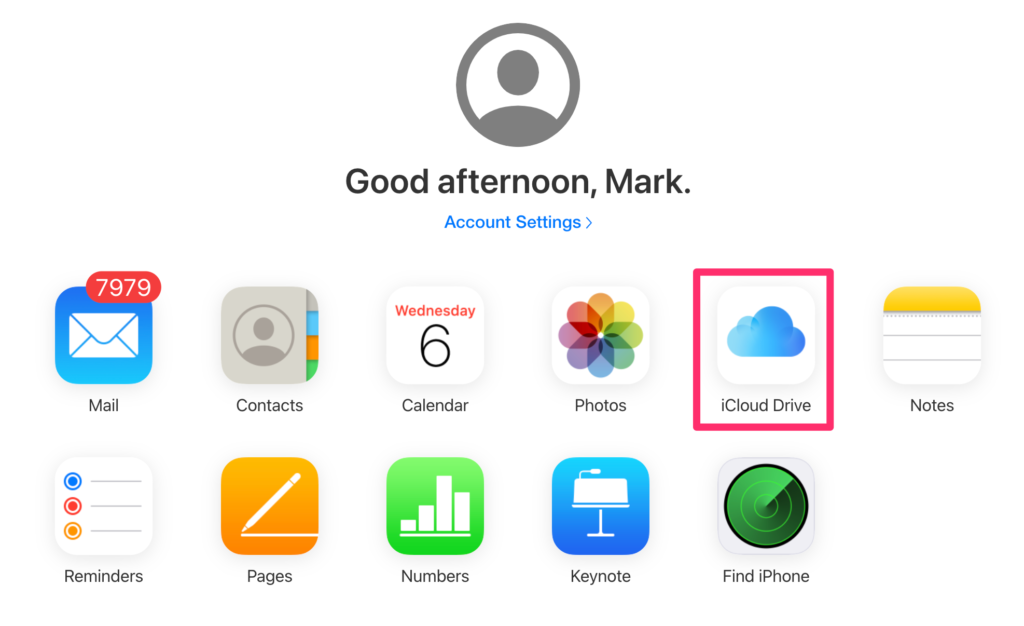

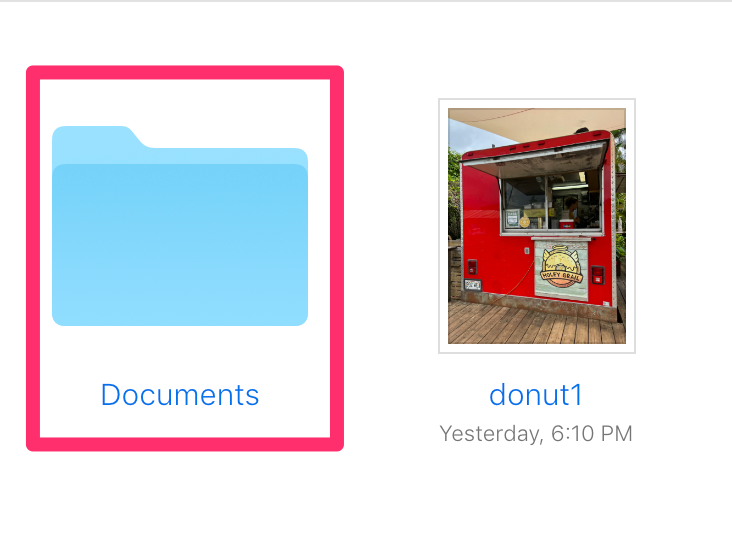

If you have long been a Macintosh user, it may surprise you to learn that any Macintosh could quickly be turned into a server. So, think of a Mac on your office desk on which you did your daily work and imagine this computer had a folder that any HTML docs placed in this folder would be immediately available on the Internet.

This option was built into all versions of the Apple OS Lion and earlier. I used to do a lot of K12 staff development sessions and I enjoyed explaining to the educators that I could turn one of their Macs into a server in less than 5 minutes. Macs are built on Linux (BSD I think) and at the time came with the Apache server software built in. Most of the servers on the Web still run on more recent versions of Apache. Anyway, the issue with the demonstration for teachers was that most computers are connected to the internet with a dynamic and not a static IP. This translates as the IP with a dynamic connection may be different each time you connect. The IP is often called a dotted quad and looks like 75.168.107.115. You can locate your present IP using this link. You can use either the dotted quad or the site name to connect to the site. The familiar approach using the site name happens through a DNS server (domain name server) so when you use the Internet you enter a site name which ends up being converted to a dotted quad. However, even with a dynamic connection, as long as you are connected others can connect to your server by using the dotted quad.

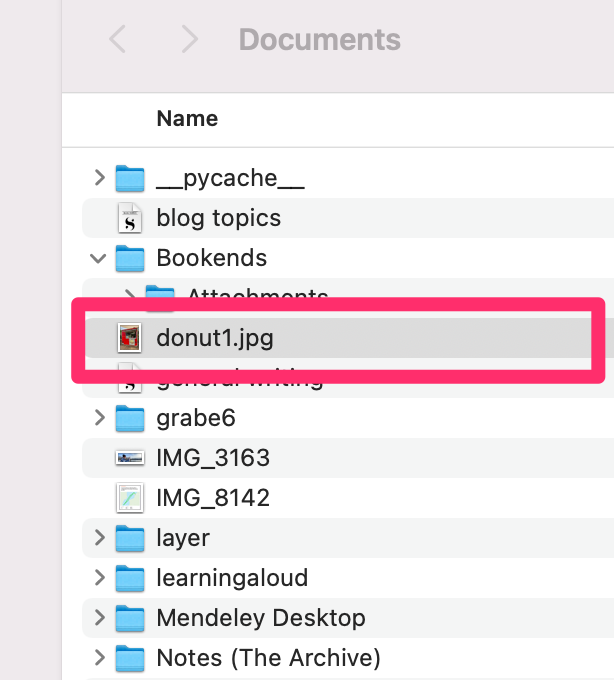

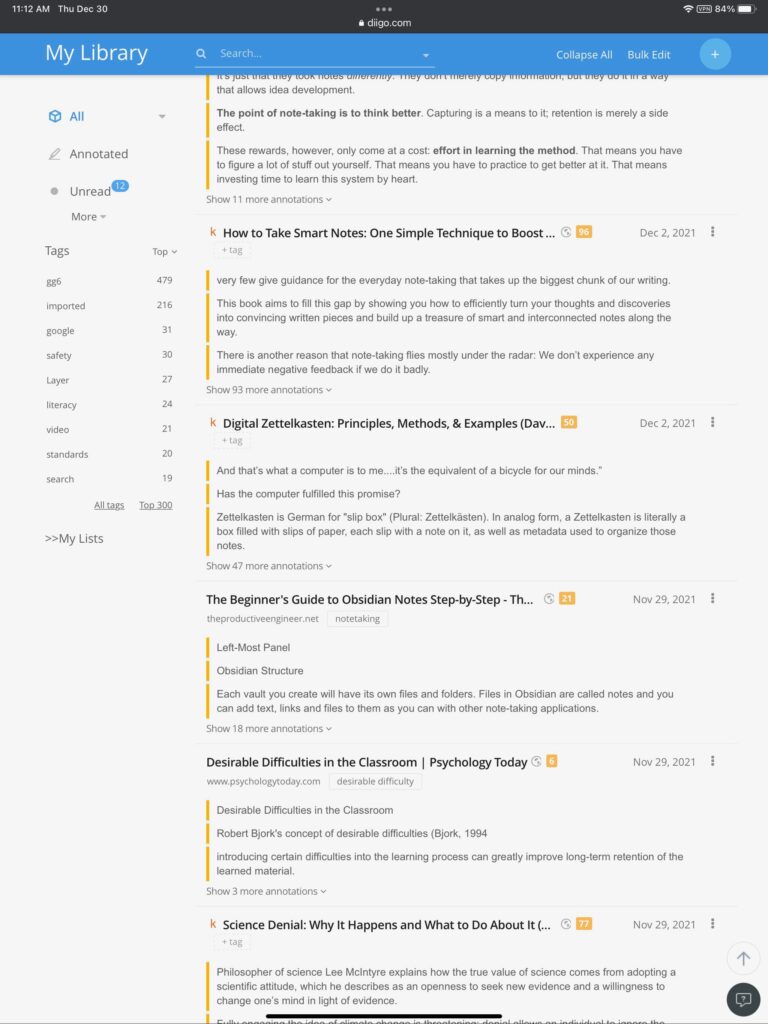

As I was remembering the tests I did using the Mac as a server, I realized there could be a way to look back in time at this behavior. The Internet Archive project operates a system called the WayBack Machine that attempts to archive Internet content for historic use. I had static Internet connections at that time and was allowed several reliable IPs because of the research I did. I remembered the address for my office desktop machine was grabe.psych.und.nodak.edu (my name, department, university) and I entered this address in the Wayback Machine. Sure enough, the page served from this desktop had been stored for posterity.

I can tell looking at this page that it was not coded in HTML by hand. At that time Apple offered a web development tool called iWeb as part of its basic productivity suite of software tools. iWeb provided a graphic interface for laying out web pages and then generated the HTML automatically. This would have been the only way I could have included something like a guestbook on the site.

So, there was a time when any user who wanted to have their own website posted from their personal server was part of the vision (the date on the page above was 2003, but Wayback says it was first created in 2001). The idea of Web 2.0 was emerging and alternate terms for this trend were the read/write web and the participatory web. The read/write web probably is the most descriptive meaning the Internet was not just for the consumption of content, but also for the creation and sharing of content. How this is done now is through a site both creators and consumers visit (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), but there was a time a different approach was being explored and anyone who wanted to operate a server could.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.