I keep encountering colleagues who disagree with me on the value of relying on digital content (e.g., Kindle books, pdfs of journal articles) rather than content they collect on paper. I agree that their large home and office libraries are visually attractive and their stuffed chair with reading lamp looks very inviting. They may even have a highlighter and note cards available to identify and collect important ideas they encounter. A cup of coffee, some quiet music in the background, and they seem to think they are set to be productive.

I have only one of my computers, a large monitor when working at my desk, and a cup of coffee. The advantages I want to promote here are related to my processing of content I access in a digital format. What you can’t see looking at my workspace whether it happens to be located in my home or at a coffee shop is the collection of hundreds of digital books and the hundreds of downloaded pdfs I have collected and can access from any locate when I have an Internet connection. I can work with digital content from my home office without a connection, but I prefer to have a connection to optimize the use of the tools that I apply.

For me, the difference between reading for pleasure and reading for productivity is meaningful. I listen to audiobooks for pleasure. I guess that is a digital approach as well and it functions whether in my home, on a walk, or in the car. For productivity, I read to take in information I think useful to understand my world and to inform my writing about topics mostly related to the educational uses of technology. I think of reading as a process that includes activities intended to make available the ideas that I encounter in what I read and in my reactions to this content in the future. Future uses frequently but not exclusively now involve writing something. At one point when I was a full-time educator I engaged in other additional forms of communication, but in retirement, I mostly write.

My area of professional expertise informs how I work. I studied learning and cognition with an emphasis on individual differences in learning and the topics of notetaking and study behavior. One way to explain my present preoccupations might be to suggest I am now interested in studying and notetaking to accomplish self-defined goals to be pursued over an extended period of time. Instead of preparing to demonstrate what I know about topics assigned to me and with priorities established by someone else with the time span of a week or at most a couple of months, I now pursue general interests of my own preparing to take on tasks I can only describe in vague terms now but tasks that may become quite specific in a year or more. How do I accumulate useful information that I can find and interpret when a specific production goal becomes immediate? The commitment I have made to consume and process digital content is based on these goals and insights.

What follows identifies the tools I presently use, the activities involved as I make use of each tool, and the interconnections among these tools and the artifacts I use each tool to produce.

Step 1 – reading.

In my professional work, I made a distinction between reading and studying. This was more for theoretical and explanatory reasons because most learners do not neatly divide the two activities. Some read a little, reread, and take notes continuously. Some read and then read again assuming I guess that a second reading accomplishes the goals of what I think of as studying. Some read and highlight and review their highlights at a later time. There are many other possibilities. I think of reading as the initial exposure to information much like listening to a lecture is an initial exposure to information. Anything that follows the initial exposure, even if interspersed with other periods of initial exposure, is studying.

My tools – Present tools/services related to this stage of processing – Kindle for books and Highlights (Mac app) for PDFs. Other tools are used for content I find online, but most of my actual productive activity focuses on books and journal articles

Step 2 – initial processing (initial studying)

While reading, I use highlighting to identify content I may later find useful and I take notes (annotation as these notes are connected to the book or pdf). Over time, I found it valuable to generate more notes. Unlike the highlights, the notes help me understand why content I found interesting at the time of reading might have future usefulness.

My tools – Present tools/services related to this stage of processing – Kindle for books and Highlights (Mac app) for PDFs. Yes, these are the same tools I identified in step 1. However, the integration of these dual roles is accurate as both functions are available within the same tools. One additional benefit of reading and annotating using the same tool and applied to the same content is the preservation of context. The digital tools I use can be integrated in ways that allow both forward and backward connections. If at a later stage in the approach I describe I want to reexamine the context in which I identified an idea, I can move between tools in an efficient way.

Step 3 – delayed processing (delayed studying)

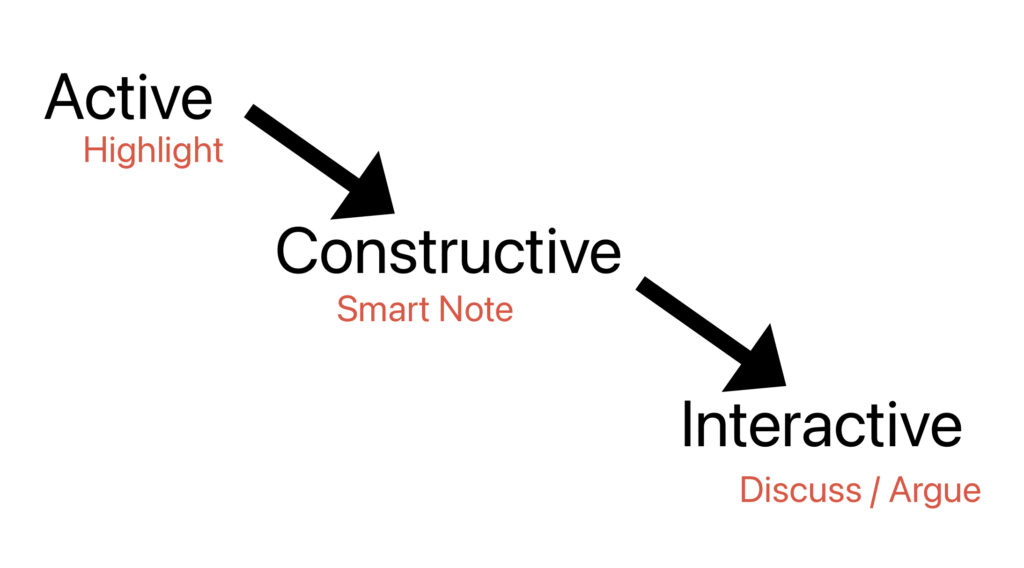

Here I list tools I would use for accepting the highlights and notes output from Step 2 as isolated from the original text. I also include tools I would use for reworking notes to make them more interpretable when isolated from context, adding tags to stored material, adding links to establish connections among elements of information, and initial summaries written based on other stored information. I like a term I picked up from my reading of material related to what has become known as personal knowledge management (PKM). A smart note is a note written with enough information that it will be personally meaningful and would be meaningful to another individual with a reasonable background at a later point in time.

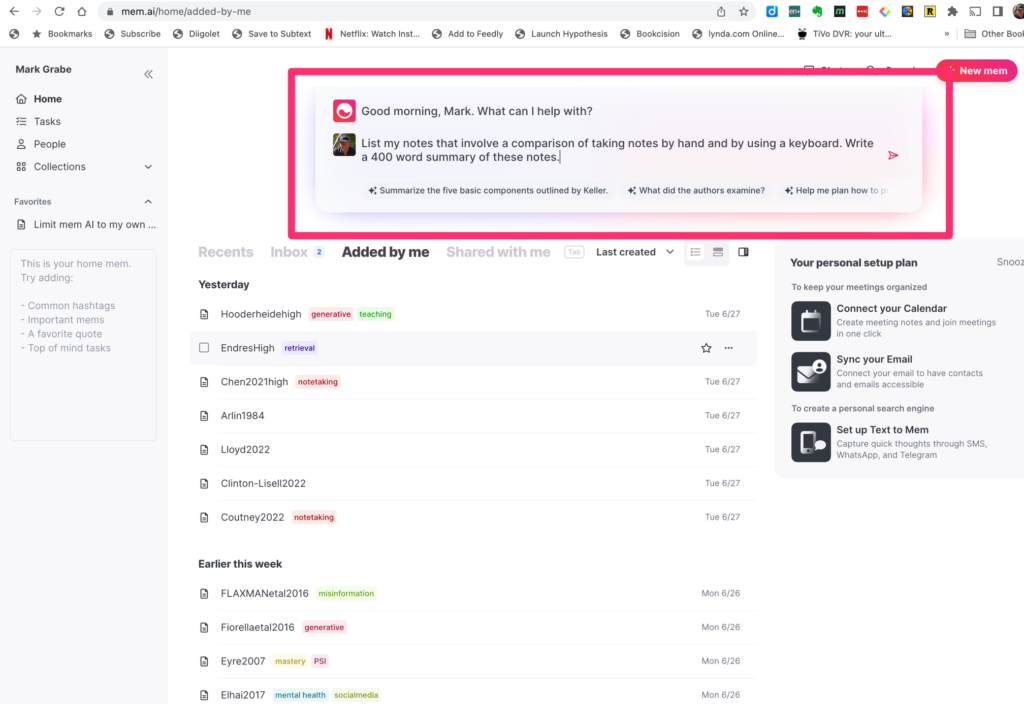

My tools – Readwise to isolate and review highlights and notes from Kindle. Obsidian to store highlights and notes, add annotations to notes, create links between notes, and generate some note-related summaries an comments. I use several AI extensions within Obsidian to “interact” with my stored content and draft some content. Presently, I use Smart Connections as my go-to AI tool. I write some more finished pieces in Google Docs.

Step 4 – sharing

As a retired academic, I no longer am involved in publishing to scientific journals or through textbook companies. My primary outlet for what I write are WordPress blogs I post through server space that I rent (LearningAloud). A cross-post a few of my blog entries to Substack and Medium.

My tools – I write in Google docs and then copy and paste to upload content to the outlets I use.

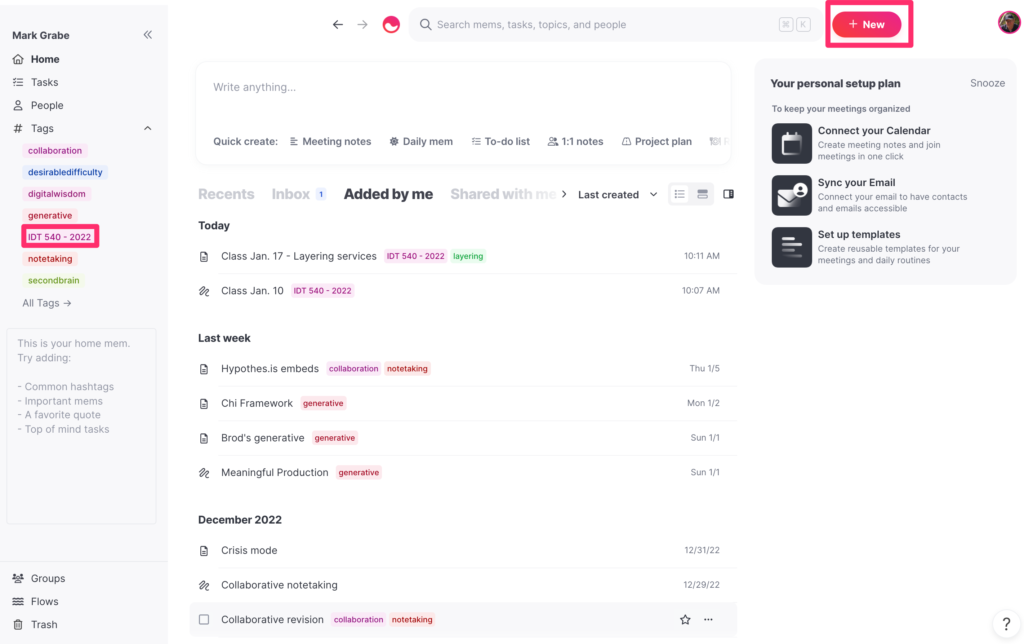

Obsidian as the hub

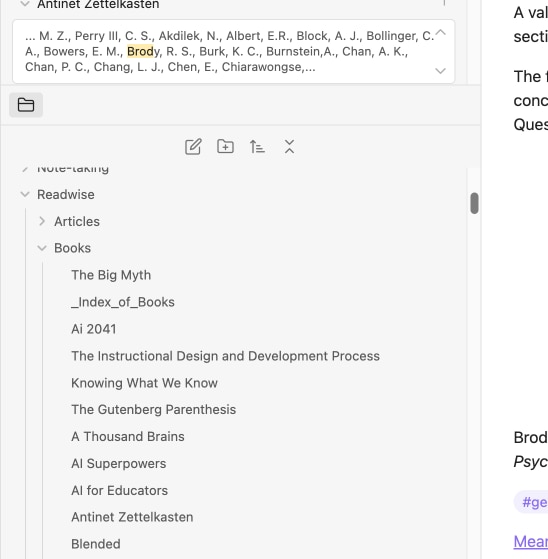

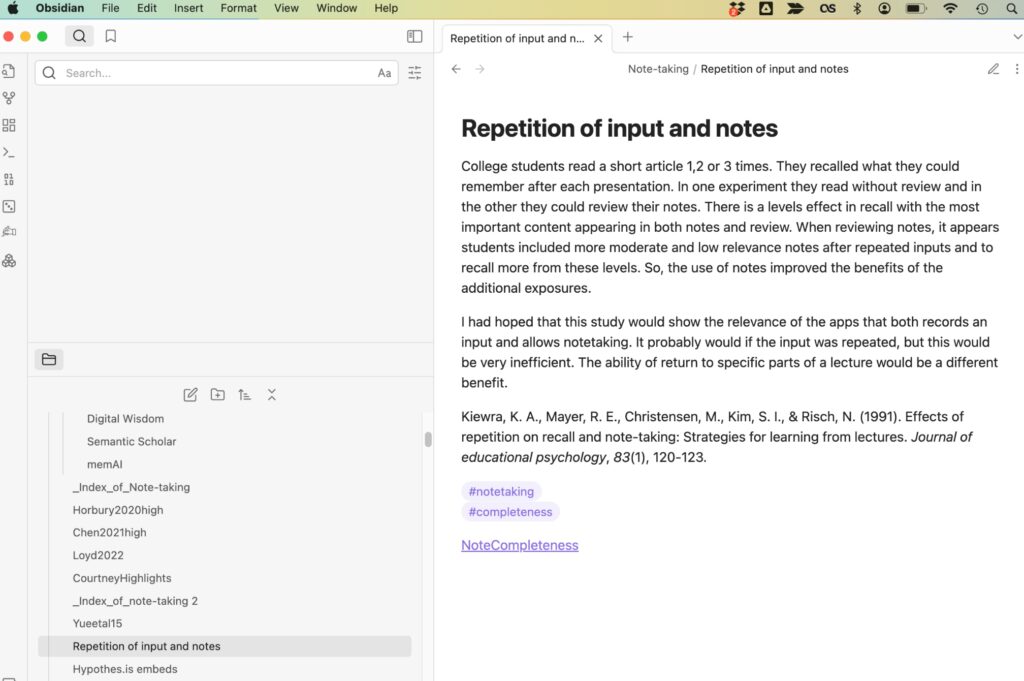

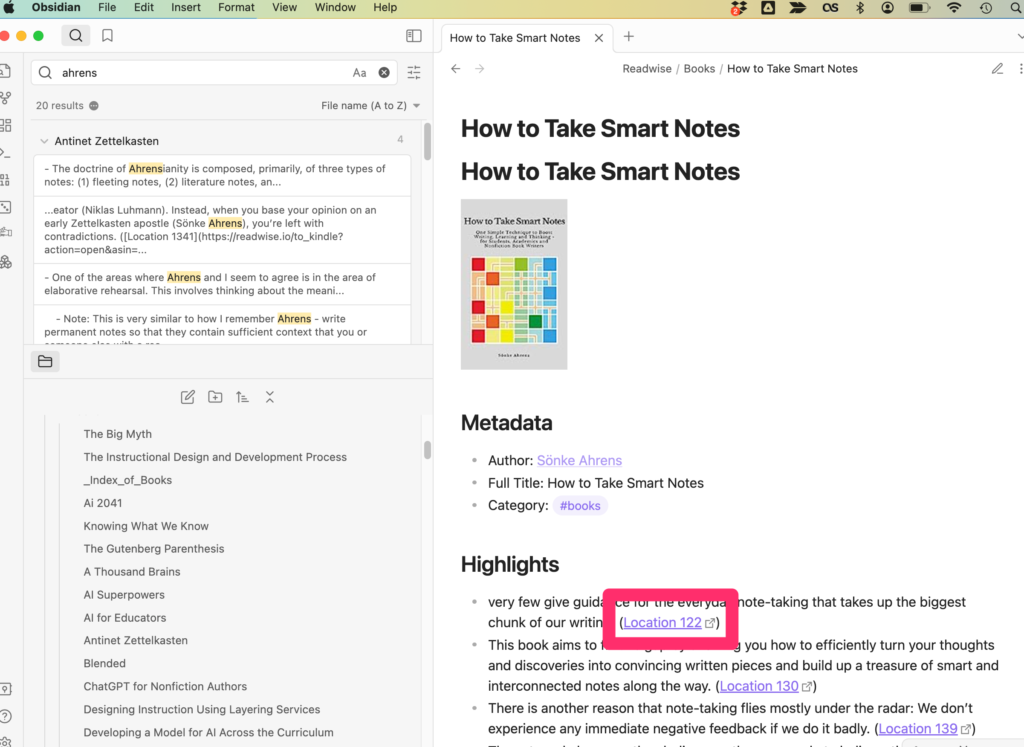

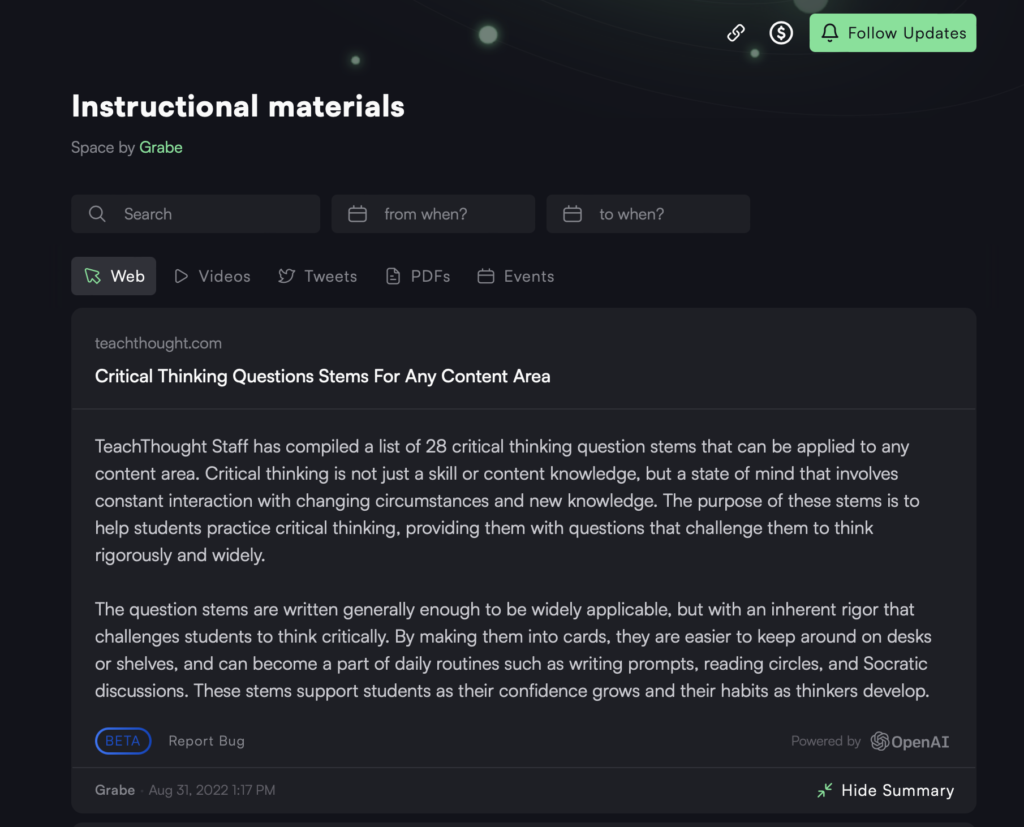

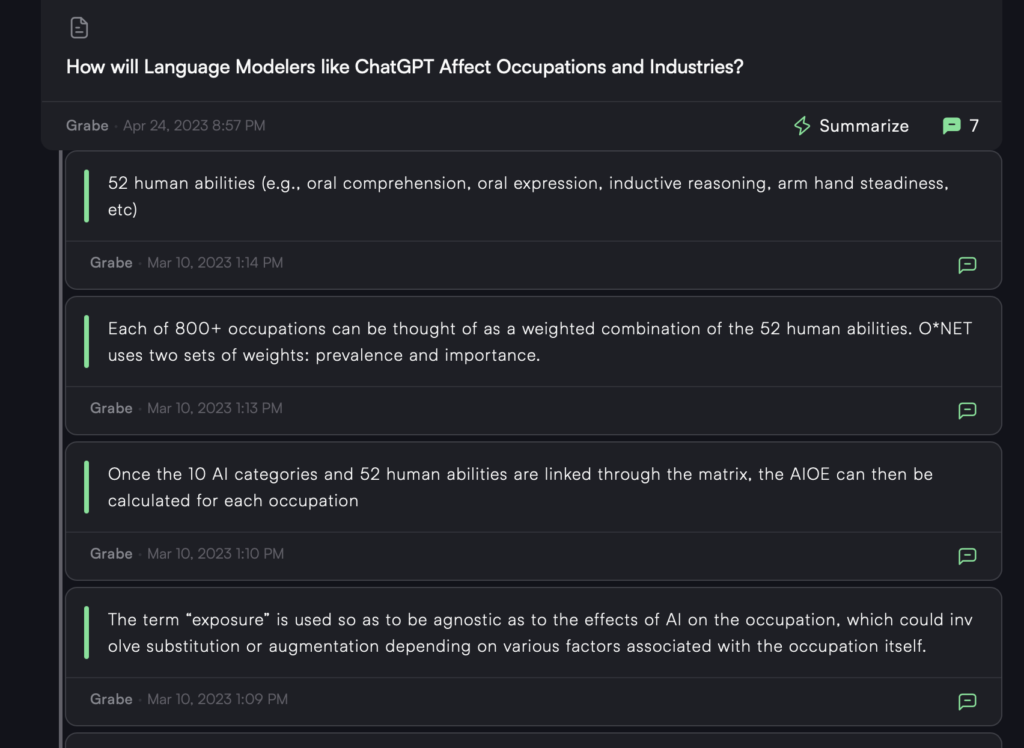

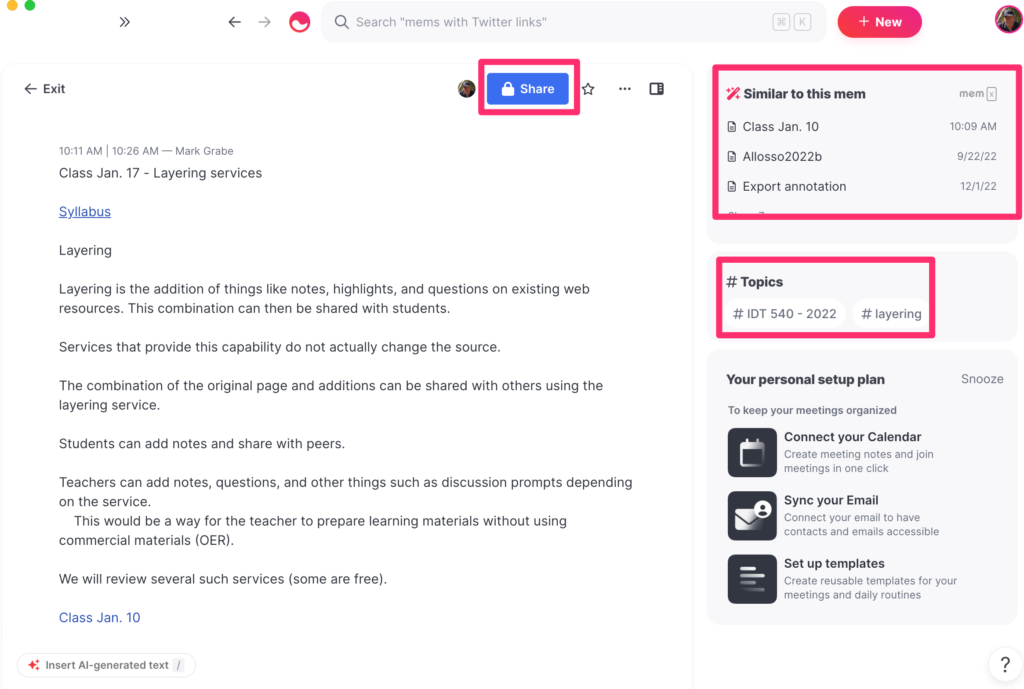

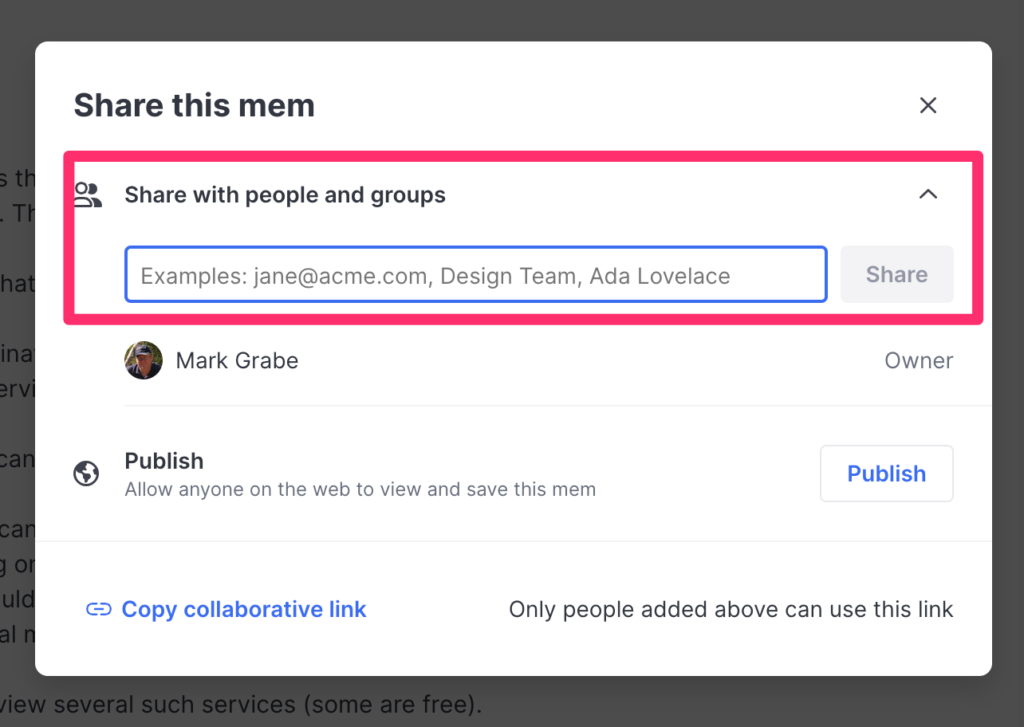

Here are a couple of images that may help explain the workflow I have described. The images show how Obsidian stores the input from the tools used to isolate highlights and notes from full-text sources.

As notes are added to Obsidian, I organize them into folders. An extension I have added to Obsidian creates an index of the content within each folder, but at some point the volume of content is best explored using search.

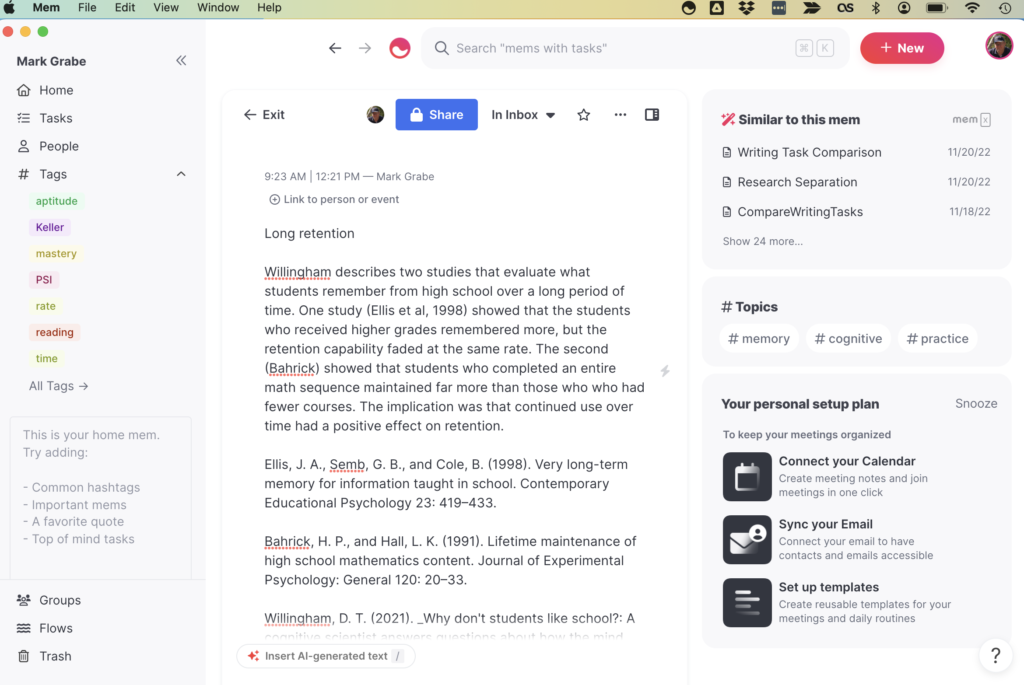

Here is what a “smart note” I have created in Obsidian looks like. The idea of a smart note is to capture an idea that would be meaningful at a later date without additional content. Included in this note is a citation for the idea, tags I have established that can be used to find related material and a link.

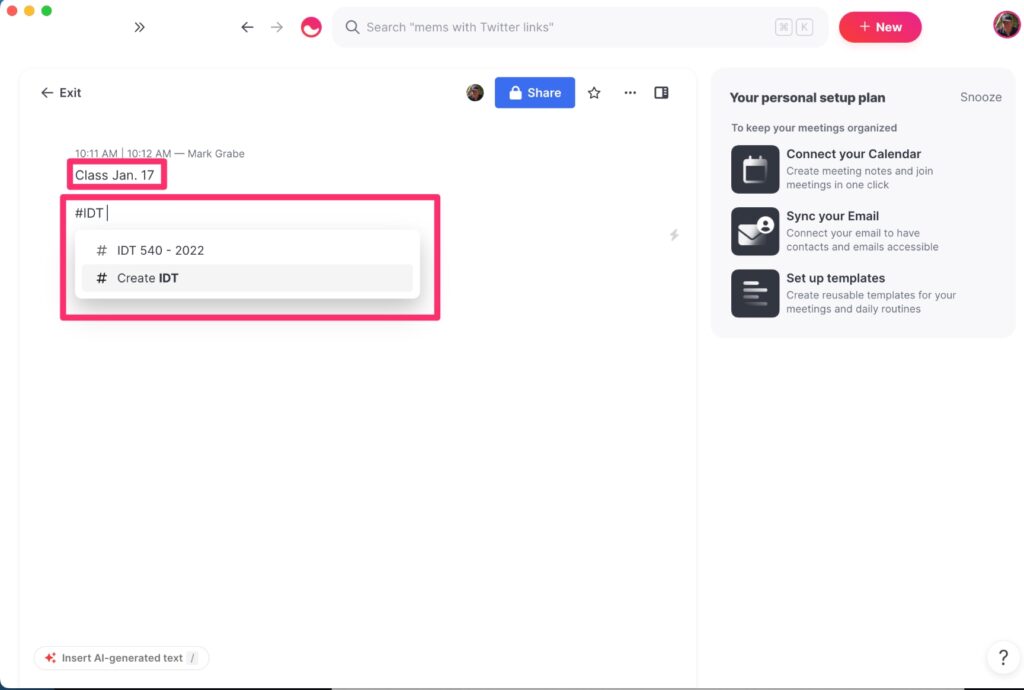

This is an example of a “note” Obsidian automatically generated based on book notes and highlights sent by Readwise. I can add tags and links to this corpus of material to create connections I think might be useful. The box identifies a link stored with the content that will take me back to Kindle and the location of the note or highlight. These links are useful for recovering the original context in which the note existed.

Here is a video explaining how my process works.

So, the argument I am making here is that digital tools provide significant advantages not considered in single-function comparisons between paper and screen. Digital is simply more efficient and efficacious for projects that develop over a period of time.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.