My favorite writer who focuses on classroom learning is Daniel Willingham. He has a way of explaining and applying research that is both approachable and actionable. My interests and vocational focus overlap with the topics of his books allowing me to be appreciative of his insights and his creative way of communicating the mindset of educators and writers and the behaviors of both highly motivated and more casual students.

Willngham’s most recent book, Outsmart Your Brain, considers notetaking multiple times as he examines several learning challenges (the large lecture, lengthy textbook assignments, labs and other hands-on activities). Taking notes in formal educational settings can differ in important ways from the writing I do about autonomous lifelong learners involved in what is often described as Personal Knowledge Management or Building a Second Brain, but he speculates about important cognitive processes rather than just offering “here is what you should do” tactics. I assume that processes generalize and with so little research focused on learning outside of formal educational settings, the commentary I offer is largely based on using what classroom-focused researchers find that would seem to apply to learning on your own.

The meaning of Willingham’s title, “Outsmart Your Brain”, is that what seems to be an easy to accomplish tactic is often the wrong choice. He differentiates the notetaking choices made when listening to lectures and reading. In contrast to many, it should be noted that Willingham supports the lecture as an important educational strategy. It is efficient as a way to communicate information, and face-to-face efficiency seems to offer better effectiveness than recorded and distributed content. The major challenge with lectures is that we tend to speak much more rapidly than individuals can write and in a large group setting feedback to a presenter is difficult to generate and would varies greatly from listener to listener. The related issue on the part of listeners is that many are unable to sort out what should be retained in notes. Often what is written is what is understood which is understandable, but an example of doing the easier thing. He notes that collaboration or instructor-provided notes offer a solution, but proposes that these resources should be used in addition to taking notes which is a generative cognitive and thus beneficial process.

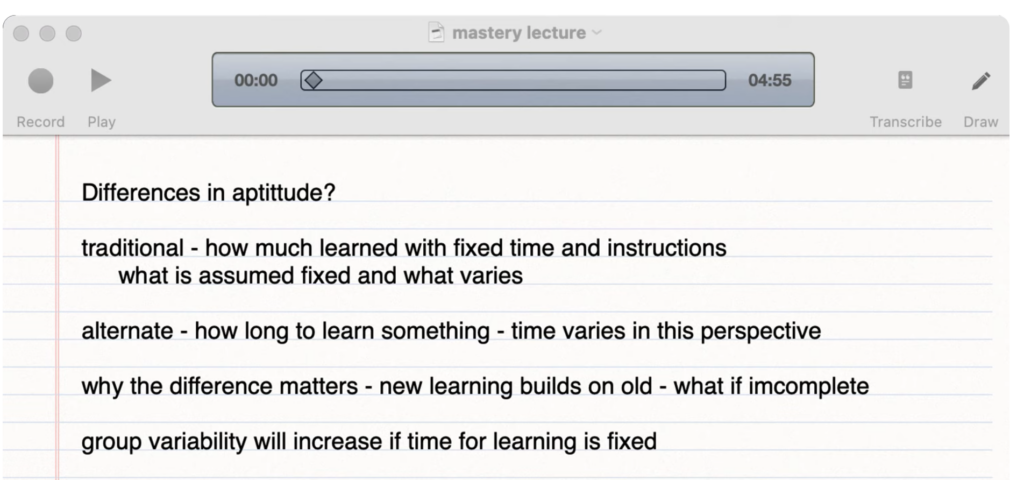

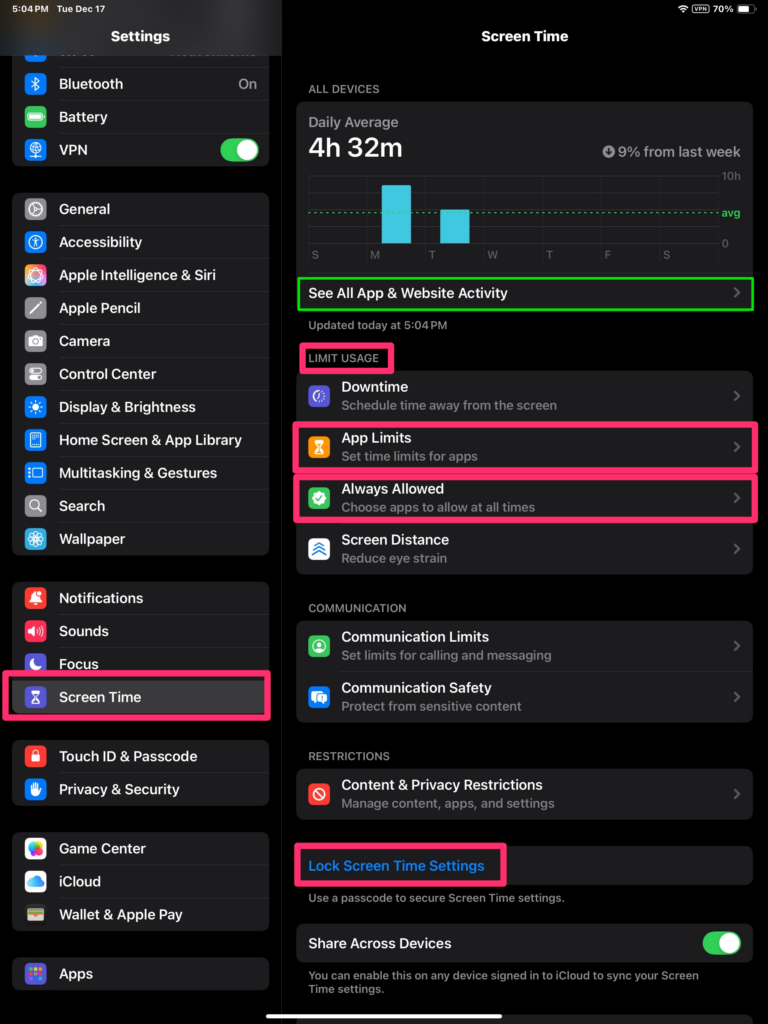

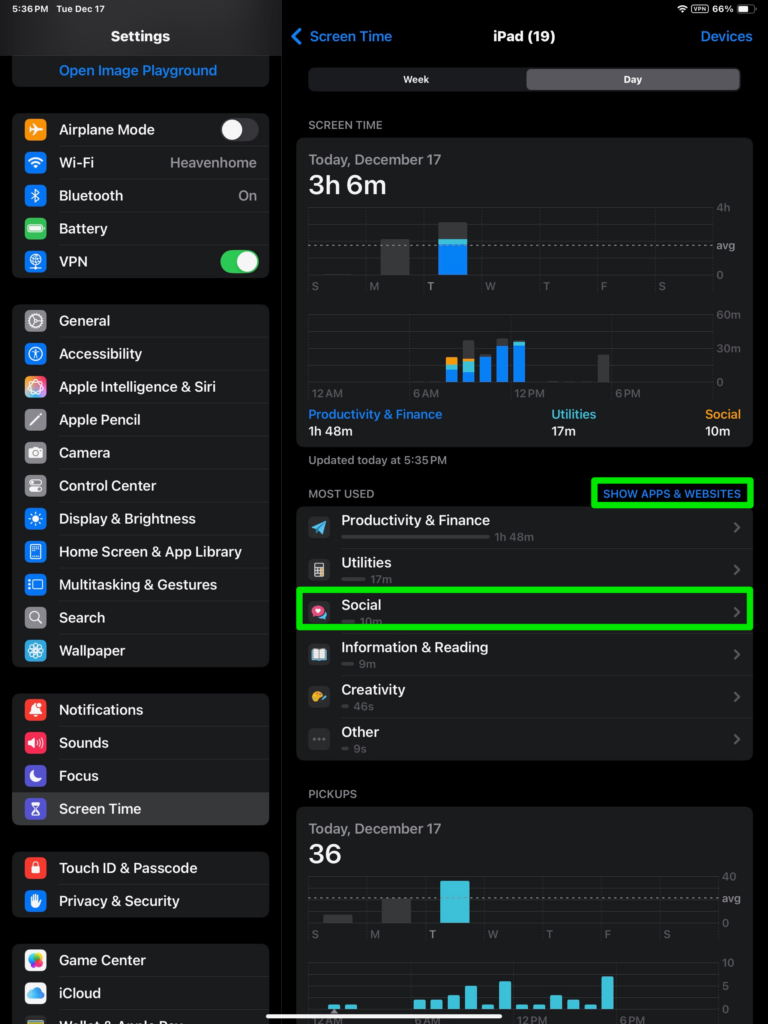

Willingham supports the researchers arguing that taking notes with pen on paper to be superior to taking notes using a digital device and as proposed in the “desirable difficulty” hypothesis proposes that the insight that more can be recorded on a keyboard provides a false sense of accomplishment. This is another example of the brain making the wrong decision. I disagree on this point and argue that Willingham ignores the opportunity a digital device can provide a written record and link audio to notes in ways that allow missed information to be re-examined. A link references the corresponding location in the audio when a note was taken. Willingham does recognize and discuss recording lectures, but discusses this opportunity as inefficient unaware I assume that the connections some apps store between notes and audio (or video) allow learners great control of how the audio is used.

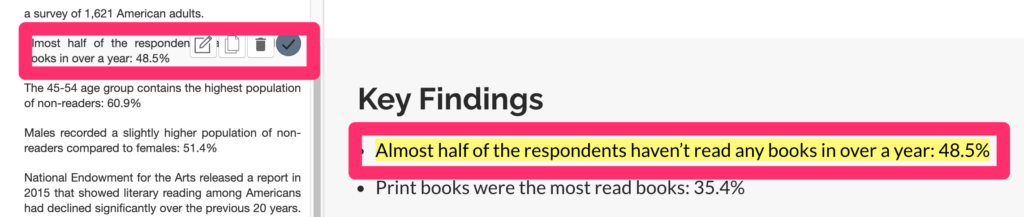

Willingham discusses note-taking as a useful addition to reading recognizing that with reading the learner does not have to deal with the lack of control present when listening. The flawed option he calls out is highlighting which again offers the learner a false sense of accomplishment. He cites an interesting study in which multiple used textbooks from the same class were examined and the finding that the text selected as important varied greatly. I could not help thinking of the “most common highlighted” option available with Kindle books.

A common issue with both lectures and books is that both tend to be hierarchical, but are experienced as sequential experiences. I interpret this problem to be one that understanding is the construction of a model of how things are interrelated. Lectures and writers tend to have this model and organize what they offer accordingly, but the experience of the learner is sequential and building a hierarchical model in real time is often too demanding. Imagine an outline that is used to develop a lecture or written product and in which the product shared moves through each part of the outline from higher to lower elements as a sequence and you can imagine the issue of reconstructing the outline. Learners can rework the content they have stored in search of this structure and presents can help by offering an overview and referring back to this overview as the presentation unfolds. Willingham speculates that learners possibly read textbooks based on their experience with fiction.

Willingham proposes two additional strategies making use of notes often ignored by students. The first is the sharing and discussion of notes within small groups. Again, this is not to replace the task of taking notes, but a way to identify ideas that have been missed or misunderstood. The second is a cross-examination of notes taken from lectures and from assigned readings. Too many seem to assume that the elimination of one source is a possible opportunity, but he argues that cross-referencing sources like cross-referencing with peers allows for additional active processing.

Summary

This was intended as more than a book review, but it is a recommendation that both educators and learners read this book. Many reviewers have noted that it should be assigned reading for new college students faced with the challenge of taking more responsibility for their own learning. The notion that the brain leads us to do things in the moment that are not necessarily the best for the future is important to recognize and the assumption that taking notes or reading a book could benefit from the consideration of nonobvious strategies deserves careful consideration. When are important study skills taught and which educators are responsible for helping learners develop these skills?

75 total views , 1 views today

You must be logged in to post a comment.