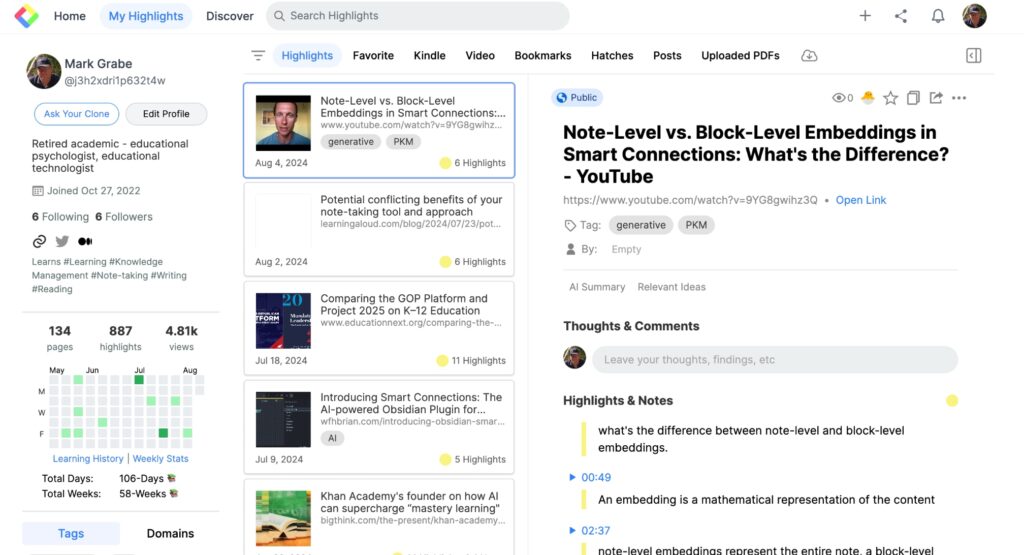

It’s not that I don’t find AI to be useful. I generate a half dozen images a month to embellish my writing. I search for journal articles I then read to examine an educational issue I want to write about. I examine what I have written to identify errors in grammar or syntax or even identify my use of passive voice which I still can’t figure out. My issue is the monthly subscription fees for the multiple tools that best suit these and other uses. It is simply difficult to justify the $20 a month fee which seems to be the going rate for each of the services and the level of use I make of each service.

I regard my use of AI as both a benefit to personal productivity, but also a subject matter I explore and write about. Writing about the intersection of technology and education is a retirement hobby and I don’t need to do what I do on a budget. However, I don’t think this is true for everyone and I can set as a personal goal an exploration of the financial issues others might need to consider. AI tools differ in how flexible they are. Often, the less flexible tools are optimized to accomplish a specific set of tasks and this narrow range increases ease of use. Users can find themselves evaluating the cost-effectiveness of options based on ease of use versus total cost.

Grammarly as an example

As someone who spends a great deal of time writing, it is worth my time to consider how AI tools can be used to improve the productivity of the time I spend writing and the quality of what I write. Grammarly is a tool suited to such goals. I have relied on both the free and pro versions of Grammarly for a quick way to edit my writing. This is a great product I find helpful. Again, the issue is the Pro version adds another $12 to the total of my monthly subscriptions bill. The free version is great for basic errors, but the pro version is necessary for complete sentence rewrites. It is helpful to compare what I said with the suggested rewrite to decide whether I want to accept the alternate version.

What I have been exploring lately is the use of more general-purpose AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Abacas.ai) as an alternative. I understood that many others were using such tools in this matter, but because I had already been using Grammarly I had not invested the time to explore how more flexible tools might be used to achieve similar goals. Here is the approach I have settled on. I use a multi-level prompt to specify what I want to learn from an evaluation of something I have written. I keep this prompt in a note app so that I can copy and paste the prompt at the beginning of the content I want to evaluate. The prompt appears below. The prompt is written to be flexible so that I can adapt it to different circumstances by adding or removing specific guidelines. For example, I realize I often write in passive voice and some tasks should not include text expressed in this way. The guideline “write in active voice” can be included when I think this approach is important. If writing for a specific age group might be a goal, a guideline related to this goal can be inserted.

To demonstrate what this prompt accomplishes, I will take what I written here to this point and apply the prompt.

Evaluate the following content using the following guidelines:

- Correct spelling errors

- Correct grammatical errors

- Correct punctuation errors

- Write in active voice

- Suggest corrections

- Only list the lines containing errors and the proposed corrections

- Add an explanation for the need for a correction

[Insert content to be evaluated here]

Response from Abacas.ai.

1. **Original:** I examine what I have written to identify errors in grammar or syntax or even identify my use of passive voice which I still can’t figure out.

**Correction:** I examine what I have written to identify errors in grammar or syntax and even identify my use of passive voice, which I still can’t figure out.

**Explanation:** Added a comma before “which” to correctly punctuate the non-restrictive clause.

2. **Original:** It is simply difficult to justify the $20 a month fee which seems to be the going rate for each of the services and the level of use I make of each service.

**Correction:** It is simply difficult to justify the $20-a-month fee, which seems to be the going rate for each of the services and the level of use I make of each service.

**Explanation:** Added a hyphen in “$20-a-month” to correctly form a compound adjective and a comma before “which” to punctuate the non-restrictive clause.

3. **Original:** I regard my use of AI as both a benefit to personal productivity, but also a subject matter I explore and write about.

**Correction:** I regard my use of AI as both a benefit to personal productivity and a subject matter I explore and write about.

**Explanation:** Replaced “but also” with “and” to correct the parallel structure.

4. **Original:** Writing about the intersection of technology and education is a retirement hobby and I don’t need to do what I do on a budget.

**Correction:** Writing about the intersection of technology and education is a retirement hobby, and I don’t need to do what I do on a budget.

**Explanation:** Added a comma before “and” to separate two independent clauses.

5. **Original:** Grammarly as an example

**Correction:** Grammarly is an example.

**Explanation:** Added “is” to form a complete sentence.

6. **Original:** Again, the issue is the Pro version adds another $12 to the total of my monthly subscriptions bill.

**Correction:** Again, the issue is that the Pro version adds another $12 to the total of my monthly subscription bill.

**Explanation:** Added “that” for clarity and changed “subscriptions” to “subscription” for correct singular form.

7. **Original:** What I have been exploring lately is the use of more general-purpose AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Abacas.ai) as an alternative.

**Correction:** What I have been exploring lately is the use of more general-purpose AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT, Abacus.ai) as an alternative.

**Explanation:** Corrected the spelling of “Abacas.ai” to “Abacus.ai.”

8. **Original:** I understood that many others were using such tools in this matter, but because I had already been using Grammarly I had not invested the time to explore how more flexible tools might be used to achieve similar goals.

**Correction:** I understood that many others were using such tools in this manner, but because I had already been using Grammarly, I had not invested the time to explore how more flexible tools might be used to achieve similar goals.

**Explanation:** Changed “matter” to “manner” for correct word usage and added a comma after “Grammarly” to separate clauses.

The feedback I have received would normally have resulted in my making several adjustments. I have not done so for you to consider both the original and the suggestions. The feedback makes specific suggestions and I either copy and paste the suggestions to the original source material or simply retype what needs to be fixed. This is clumsier than just clicking on the recommendation offered by Grammarly and it often requires that I use the search function in a longer text to locate the offending sentence. When writing on my desktop machine I simply open a second window and move between one window with the AI feedback and the original document to make adjustments.

71 total views

You must be logged in to post a comment.