In reviewing the various ways I might use AI, I am starting to see a pattern. There are uses others are excited about that are not relevant to my life. There are possible uses that are relevant, but I prefer to continue doing these things myself because I either enjoy the activity or feel there is some personal benefit beyond the completion of a given project. Finally, there are some tasks for which AI serves a role that augments my capabilities and improves the quality or quantity of projects I am working on.

At this time, the most beneficial way I use AI is to engage an AI tool in discussing a body of content I have curated or created as notes and highlights in service of a writing project I have taken on. There are two capabilities here that are important. First, I value the language skills of an AI service, but I want the service to use this capability only as a way to communicate with me about the content I designate. I am not certain I know exactly what this means as it would be similar to saying to an expert with whom I was interacting tell me about these specific sources without adding in ideas from sources I have not asked you to explore. Use your general background, but use this background only as a way to explain what these specific sources are proposing. What I mean is don’t add in stuff to address my prompt that does not exist within the sources I gave you.

Second, if I ask an AI service about the content I have provided, I want the service to be able to identify the source and possibly the specific material within a source that was the basis for a given position taken. Think of this expectation as similar to the expectation one might have in reading a scientific article to which the author provides citations for specific claims made. My desire here is to be able to evaluate such claims myself. I have a concern in simply basing a claim on the language of sources not knowing the methodology responsible for producing data used as a basis for a claim. For serious work, you need to read more than the abstract. Requiring a precise methodology section in research papers is important because the methodology establishes the context responsible for the generation of the data and ultimately the conclusions that are reached. Especially in situations in which I disagree with such conclusions, I often wonder if the methodology applied may explain the differences between my expectations and the conclusions reached by the author. Human behavior is complex and variables that influence behavior are hardly ever completely accounted for in research. Researchers do not really lie with statistics, but they can mislead by broad conclusions they share based on a less-than-perfect research method. There are no perfect research methods hence the constant suggestion that more research is needed.

Several services approximate the characteristics I am looking for. I will identify three such services. I had hoped to add a fourth, but I intended to subscribe to the new OpenAI applications recently announced, but the $20 a month subscription fee necessary to use these functions was recently suspended so I will have to wait to explore these functions until OpenAI decides to expand the user base.

The three services I have worked with include NotebookLM, Mem.ai, and Smart Connections with Obisidan. I have written about Mem.ai and Smart Connections in previous posts, so I will use NotebookLM for extended comments and then offer quick examples produced by the other two services.

NotebookLM

NotebookLM recently was made available to me so I have had less experience using this tool than the other two I have included.

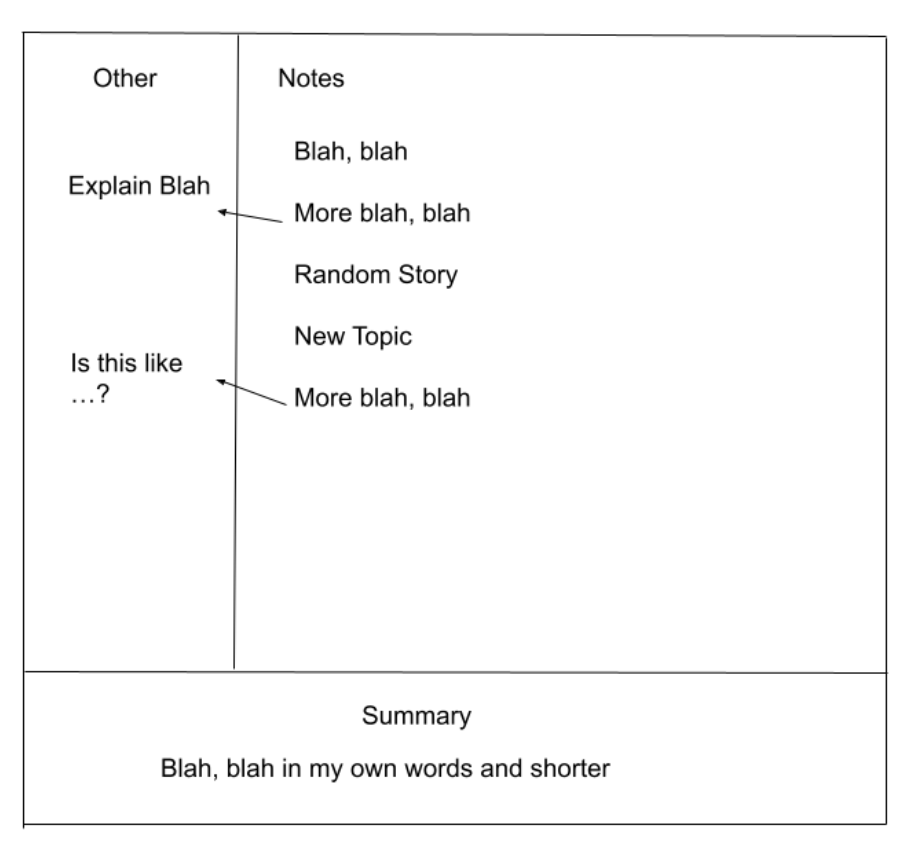

At this time you can create a notebook based on 5 pdfs or 10 text segments. There is a limit to how much content these units of information can total, but the pdfs I used were research articles so this is a lot of content. In the following image, icons for the 5 pdfs appear in the column on the left of the screen. All of the pdfs have been selected for the interaction I intend with the AI tool and a check beside each pdf indicates this is the case. The window for submitting my prompts appears at the bottom of the image.

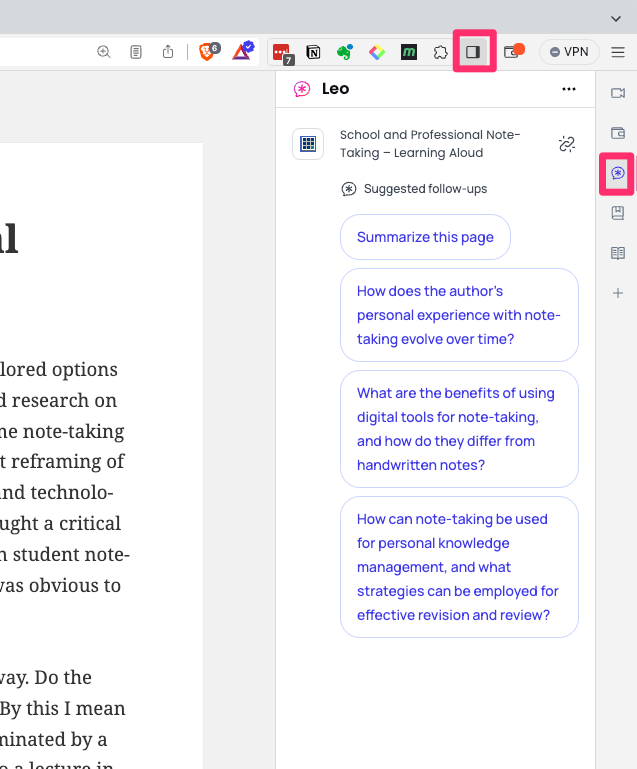

The second image shows the results from the prompt I have submitted (I will explain my interest in interacting with these pdfs following this description). The response to this query is provided above the prompt window (I will share the text) and below this window you will see that the summary was based on 10 “citations”. Selecting one of these citations brings up the content that now appears in the left-hand column. This window shows the content of the pdf and some summary comments about that document generated by the AI. The AI also proposes additional prompts a user might want to apply to that content.

The task I asked all three services to address was related to a recent post I wrote describing generative cognitive tasks and comparisons among the impacts of these generative activities. The pdfs were research studies I had reviewed and were the basis for that post. I had detailed familiarity with this content from both reviewing and annotating this material and writing the previous post and I use this approach of first engaging a process without AI to provide a basis for commenting on what the AI provides. The prompt that follows is what I submitted to NotebookLM to see what would be generated. I will use a similar prompt with the other two AI services/

Prompt: Use only my notes, generate a 400 word summary of generative learning activities and include what is known about the relative effectiveness of different activities.

NoteBook response

Generative learning is a type of learning in which students are actively engaged in creating new knowledge by interacting with the material. This is in contrast to passive learning, in which students simply listen to a lecture or read a textbook.

Generative learning activities are designed to encourage students to think critically about the material and to make connections between new information and their existing knowledge.

There is a significant body of research evidence that supports the effectiveness of generative learning activities. A meta-analysis of 500 studies found that generative learning activities resulted in better learning outcomes than traditional, passive learning methods (Coffey et al., 2003).

Some of the most effective generative learning activities include:

- Summarizing: Students are asked to summarize a text in their own words. This activity helps students to identify the main ideas of the text and to understand the relationships between them.

- Questioning: Students are asked to generate questions about a text. This activity helps students to think critically about the text and to engage with the material in a deeper way.

- Discussion: Students are asked to discuss a text with their classmates. This activity helps students to share their understanding of the text and to learn from each other.

The relative effectiveness of different generative learning activities depends on the specific learning goals. For example, summarizing is a good activity for helping students to remember information, while questioning is a good activity for helping students to understand the material in a deeper way.

Generative learning activities can be used in a variety of settings, including K-12 classrooms, higher education, and corporate training. They are a valuable tool for helping students to learn and remember new information in a more effective way.

***

You will note in this material that NoteBook included a reference. This was not one of the pdfs I provided for review so I thought it might have been included in the reference section of one of the pdfs. I asked Notebook to provide a full citation and it generated the following.

Coffey, J. E., & McDonald, J. (2003). The effects of generative learning activities on student achievement: A meta-analysis. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 28(4), 240-263. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2003.09.001

While this citation looks authentic and has the proper APA format, it is made up. I tried searching Google Scholar and used my library online access to search the location in Contemporary Educational Psychology and no such article exists. Google asks for user feedback and I provided the fake citation in my evaluation.

***

Mem.AI

My use of Mem.ai and Smart Connections require a little different approach. The content stored in these services results from my exporting notes and highlights from the research articles I read. Both services are directed at my entire collection of notes so this is different from what NotebookLM could access. However, the citations indicated that the output was based on very similar source material.

Prompt: Use only my notes, generate a 400 word summary of generative learning activities and include what is known about the relative effectiveness of different activities.

Mem.ai response

Generative learning is a process where learners actively engage with material, creating new knowledge and connections. This approach involves strategies such as summarization, teaching, self-testing, and self-explaining, which require learners to select and organize relevant information, elaborate on the material based on personal knowledge, and integrate new information with existing knowledge 1^.

Fiorella and Mayer (2016) identified eight strategies that promote generative learning, including summarization, mapping, drawing, imagining, self-testing, self-explaining, teaching, and enacting. These strategies help learners to create a product based on existing knowledge 1^.

Brod (2021) focused on age differences in generative learning strategies and emphasized the importance of producing a meaningful product that goes beyond simple paraphrasing or retelling. For instance, highlighting does not result in new content, but summarization does. Brod’s review suggests that summarizing becomes useful from high school onwards, while testing is beneficial for all ages 2^.

Chi’s (2009) framework differentiates learning activities into active, constructive, and interactive categories. Active engagement with the material can activate existing knowledge and store new input, while constructive activities involve creating a product based on existing knowledge. Interactive activities involve engaging with others to produce a product that integrates external input with personal knowledge 1^.

Fiorella (2023) proposed a new framework of sense-making that distinguishes among three sense-making modes—explaining, visualizing, and enacting—that serve unique and complementary cognitive functions. The explaining mode generalizes knowledge, the visualizing mode organizes knowledge, and the enacting mode simulates knowledge 3^.

In conclusion, generative learning involves actively engaging with the material to create new connections and deeper understanding. The effectiveness of different generative learning activities can vary based on factors such as age and the specific learning context. However, strategies such as summarization, teaching, self-testing, and notetaking with revision and elaboration can promote generative learning and enhance understanding of the material.

Summarize my notes on generative learning Tue 4/18

Brod’s generative Fri 4/14

Fiorellaet2023 Fri 10/13

1^: Summarize my notes on generative learning

3^: [Fiorellaet2023](https://mem.ai/m/cqo3CLWb5tkb8syut

At the end of each paragraph in this output, you see a number. The number corresponds to the citation at the bottom. About the three links that take a user to that note, you see the names of the notes. So, this output is carefully linked to sources. I will provide an example of what my notes look like in association with the output from Smart Connections, but each note contains a citation of the article from which I created that note.

***

Smart Connections (within Obsidian)

Obsidian contains my notes from research articles I have read and also highlights from other sources provided to Obsidian through Readwise. I tell you this again because I do not have a comparison among AI services based on exactly the same base of resources. However, again, you will note similar sources are found. Note also that the prompt is a little different to get Smart Connections to include citations.

Prompt: Use only my notes, generate a 400 word summary of generative learning activities and include what is known about the relative effectiveness of different activities. Include links to the individual source notes within your summary

Response:

Based on your notes, generative learning involves actively making sense of new information by mentally reorganizing and integrating it with one’s prior knowledge (Fiorella and Mayer, 2016). It is a constructive process that requires learners to select important information, reorganize it, and relate it to what they already know (Fiorellaetal2016).

Fiorella and Mayer (2016) identified eight strategies that promote generative learning: summarizing, mapping, drawing, imagining, self-testing, self-explaining, teaching, and enacting. Summarizing involves selecting the main ideas, organizing them into a logical structure, and integrating new information with prior knowledge (Fiorellaetal2016). It is more effective for relatively simple concepts and requires training to use effectively (Fiorellaetal2016).

Mapping and drawing also involve transforming information into different forms of representation (Fiorellaetal2016). These strategies help learners build connections and organize the material (Fiorellaetal2016).

Self-testing, or retrieval-based learning, requires learners to actively retrieve information from memory without access to the provided materials (Fiorellaetal2016). It strengthens memory and makes it more accessible in the future (EndresHigh).

Self-explaining involves explaining the content of a lesson to oneself during learning (Fiorellaetal2016). It promotes meaningful learning outcomes when learners engage in reflective knowledge building (Fiorellaetal2016).

Teaching, on the other hand, involves selecting relevant information, organizing it into a coherent structure, and elaborating on it by incorporating existing knowledge (Fiorellaetal2016). It sets itself apart from other generative strategies by focusing on helping others learn (Fiorellaetal2016).

Based on the research by Fiorella and Mayer (2016), it is more appropriate to consider each generative strategy as suitable for certain types of learning and learning contexts rather than regarding one strategy as the most effective (Fiorellaetal2016).

In a study by Koh, Lee, and Lim (2018), the learning benefits of teaching were investigated. The results showed that teaching improved learning outcomes when it involved retrieval practice, but not when learners used a prepared script (Generative > TeachingAsRetrieval). This supports the idea that retrieval practice is an effective generative learning activity.

Overall, generative learning activities have been shown to be effective in promoting meaningful learning outcomes. However, the effectiveness of each activity may vary depending on the complexity of the material and the training provided to learners. It is important to consider the specific learning goals and contexts when selecting and implementing generative learning strategies (Fiorellaetal2016).

Based on your notes, here are the individual notes that provide more information on each generative learning activity:

– [[Generate1]]: Provides an overview of generative learning theory and the eight strategies identified by Fiorella and Mayer (2016).

– [[Summarizing]]: Describes the summarizing strategy and its effectiveness in selecting main ideas and creating quality summaries.

– [[Teaching]]: Discusses the goal of teaching and its distinction from other generative strategies.

– [[Self-Testing]]: Explains the self-testing strategy and its role in retrieval-based learning.

– [[Promote generative learning]]: Provides a link to the article by Fiorella and Mayer (2016) that identifies the eight strategies and discusses their effectiveness.

– [[Fiorellaetal2016]]: Summarizes the key points from Fiorella and Mayer’s (2016) article on generative learning strategies.

– [[EndresHigh]]: Discusses the importance of task differences in retrieval practice and the effects of different types of recall tasks.

– [[Yang2021]]: Highlights a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of retrieval practice in classroom learning and raises questions about the mechanism and student perception of its benefits.

***

Note: The output of Smart Connections is in markdown and the terms included in double parentheses are links that connect to the source note. So, if the summary above was opened in an app that would interpret markdown, the text within the double parentheses would appear as a link and the link would take me to a file stored on my computer. The file is named Generate1.

Here is an example of one of the original notes that was identified as source material.

Generative learning makes sense of new information by reorganizing it and relating it to existing knowledge. This position comes from Wittrock, but is similar to other theorists (Mayer, Piaget). This specific article identified eight learning strategies that promote generative learning and provides a review of research relevant to each strategy.

[[Summarizing]]

Mapping

Drawing

Imagining

[[Self-Testing]]

Self-Explaining

[[Teaching]]

Enacting

The first four strategies (summarizing, mapping, drawing, and imagining) involve changing the input into a different form of representation.

The final four strategies (self-testing, self-explaining, teaching, and answering practice questions) require additional elaboration.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Eight ways to promote generative learning. _Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 717-741.

***

Summary

Keeping in mind my recognition that the AI of the three AI services was applied to slightly different content, I would argue that Smart Connections and Mem.ai are presently more advanced than NotebookLM. Eventually, I assume a user will be able to direct NotebookLM at a folder of files so the volume of content would be identical. Google does acknowledge that Notebook is still in the early stages and access is limited to a limited number of individuals willing to test and provide feedback. The content generated by all of the services was reasonable, but NoteBook did hallucinate a reference.

My experience in comparing services indicates it is worth trying several in the completion of a given task. I have found it productive to keep both Smart Connections and Mem.ai around as the one I find most useful seems to vary. I do pay to use both services.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.