Many of my recent posts have focused on note-taking and annotation. These activities have long been a personal interest. New opportunities to use these strategies in a digital environment have rekindled my interest and I have been trying to find ways I can share recommendations that bring these skills into middle school and secondary school settings.

One important observation I have found in several of the sources I have read is that learners are seldom taught to take notes or annotate. There are now many researchers and educators writing about taking better notes for the implementation of a PKM (personal knowledge management) system or a second brain. The emphasis here is a little different than the emphasis that might apply in classrooms. With PKM, you are creating notes for your use that fit your personal goals. Perhaps you want to build up resources you can use in writing blog posts or perhaps you want to store specific methods for solving a coding challenge. With classroom applications of annotation, you are usually trying to process and store important ideas provided by someone else. Perhaps you are preparing for an examination or to complete some other assignment that will follow a reading task. Students may take notes from presentations, but often take few notes or add few annotations when reading. Whether experiences exist or not, the opportunities to learn to apply such learning strategies are few.

I have located several sources that propose how annotation and note-taking skills can be taught to younger learners. These primarily are focused on adding highlights and margin notes to content on paper and typically these approaches suggest that educators make copies of content from sources that students can mark up without concern for damaging resources not intended for annotation. I provide several of these sources at the conclusion of this post and encourage interested educators to take the time to read one or more of these sources. The sources provide step-by-step approaches to teach the skills of note taking and annotation.

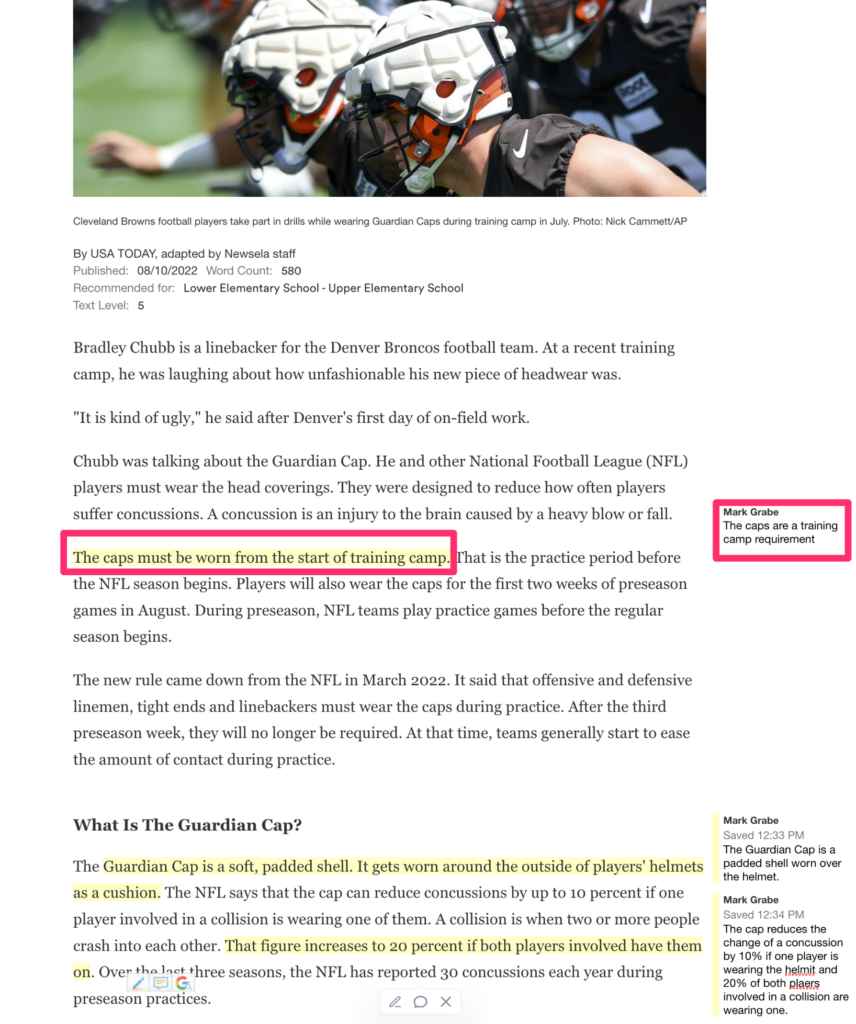

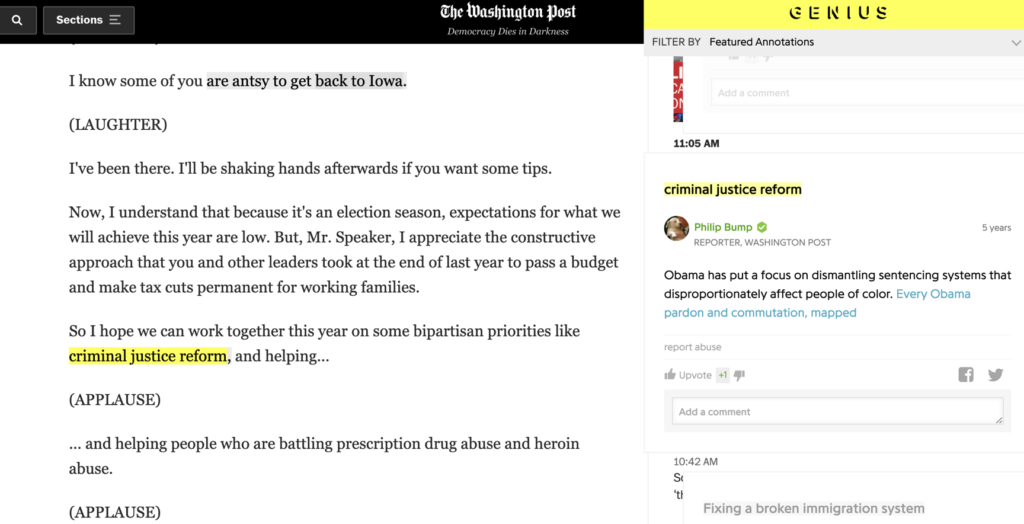

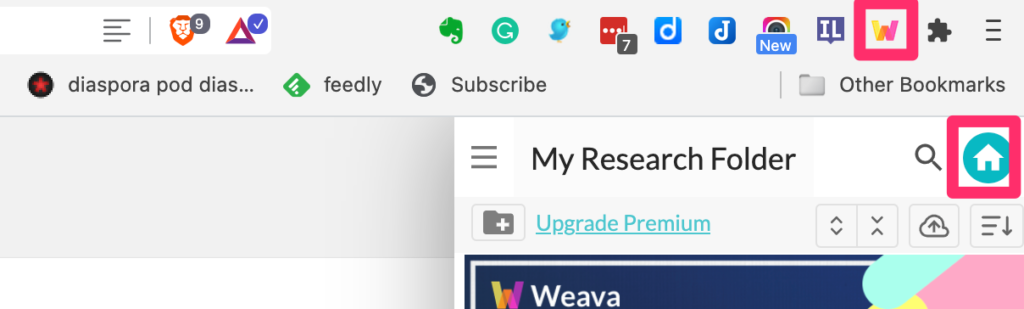

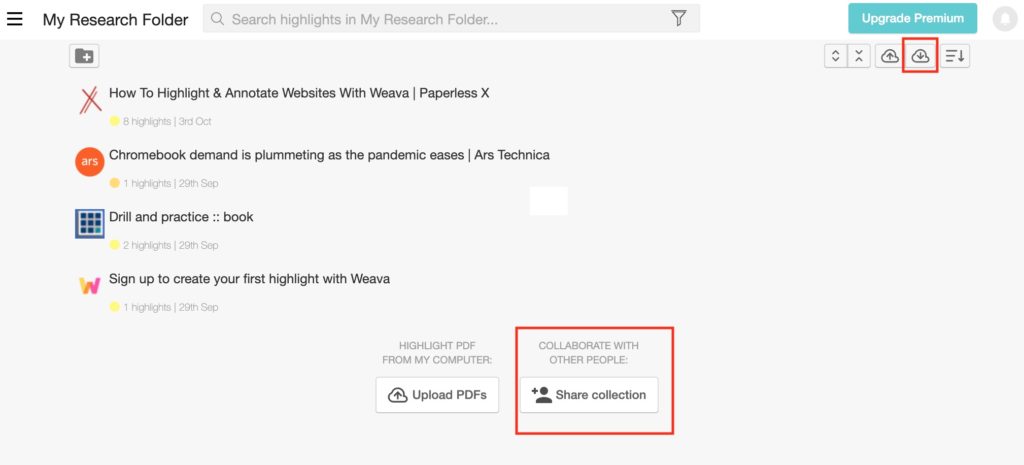

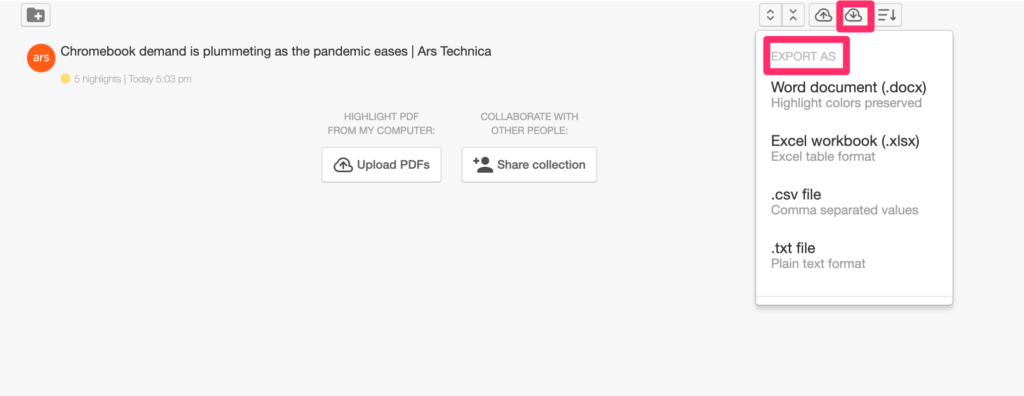

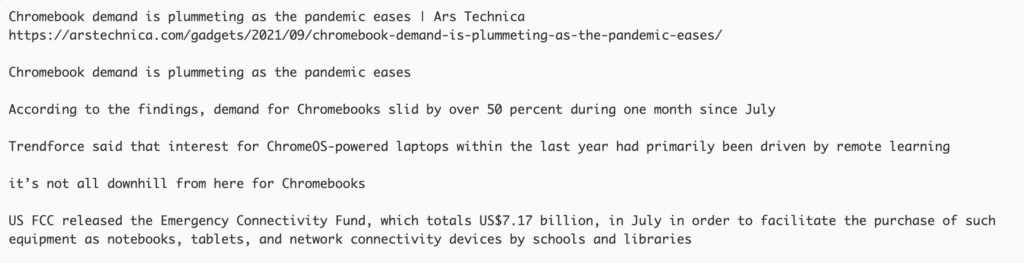

My interest here is in proposing a digital source and opportunity for annotating and highlighting that is readily available and efficient to use. You don’t have the problem of marking up what are intended to be reusable commercial materials with digital content. Most teachers are probably familiar with Newsela. This service provides reading material for most content areas (e.g., science, current events) with the unique opportunity to assign a variation of a given article at different reading levels. This allows a teacher to individualize a reading task within a class and have all students read about the same topic. The content comes with comprehension questions and other learning activities.

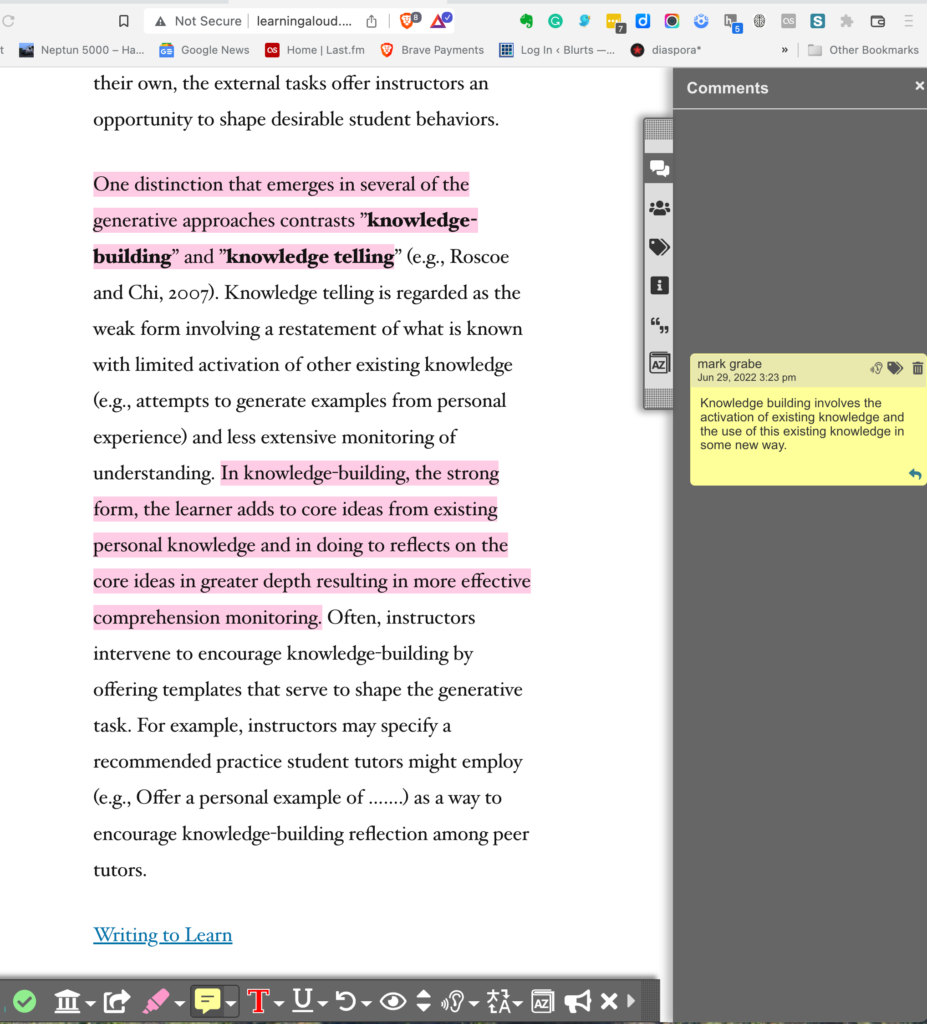

The capability of the Newsela environment that I am promoting here allows the teacher and individual students to annotate (highlight, take notes). I have written about this capability some time ago and I remembered this capability when I was trying to think of something I could suggest for educators interested in teaching annotation skills in a digital environment. Newsela provides its own explanation of how to annotate text.

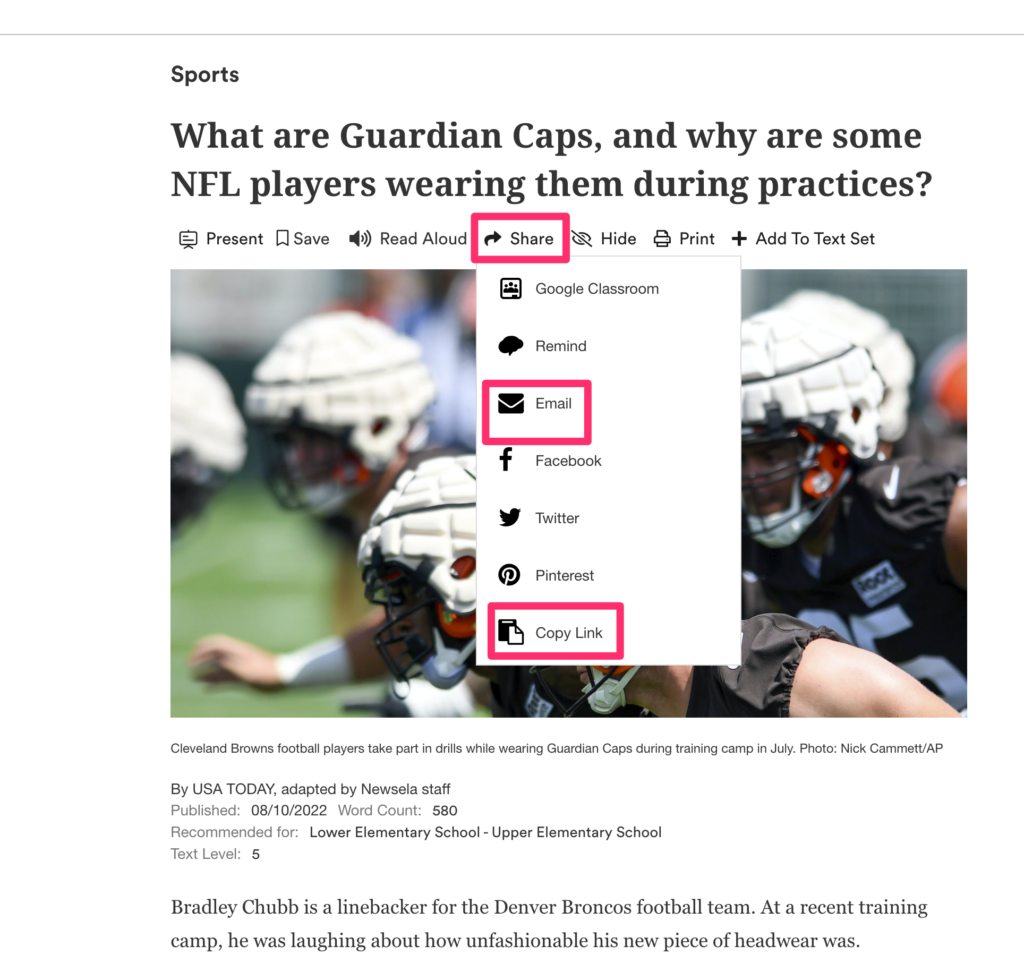

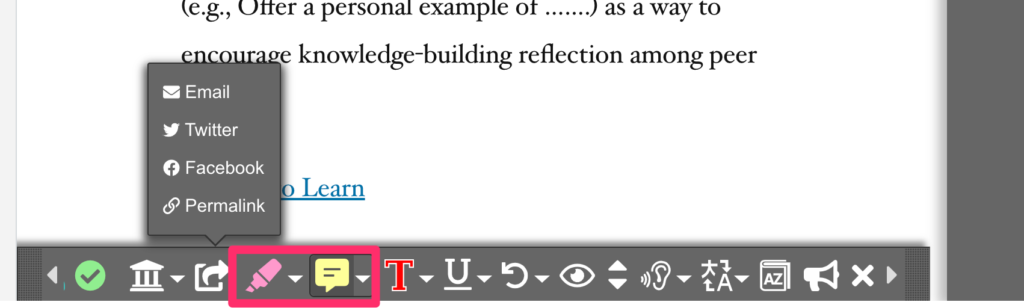

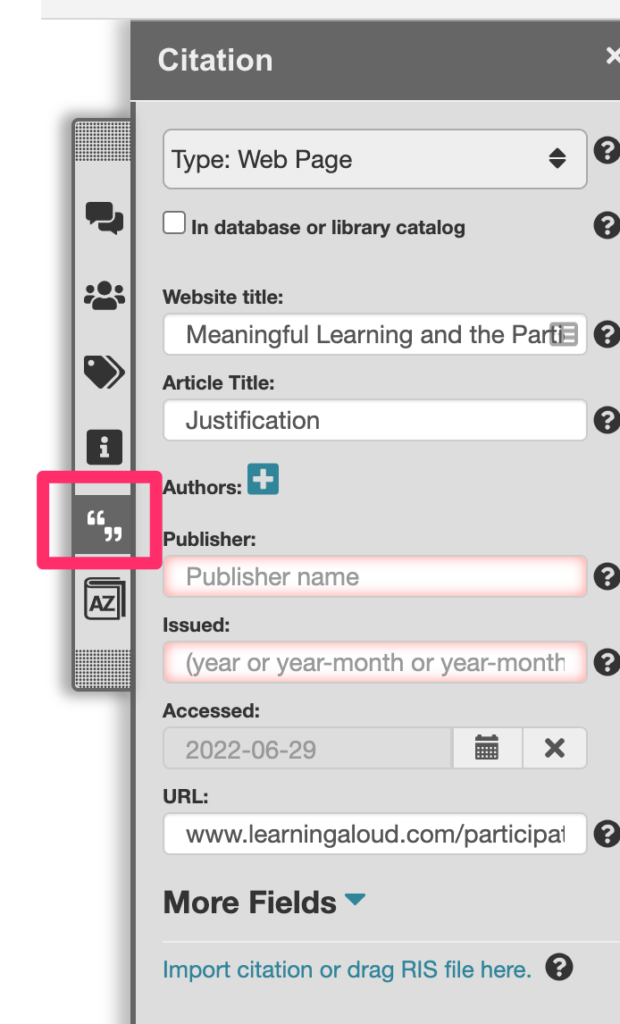

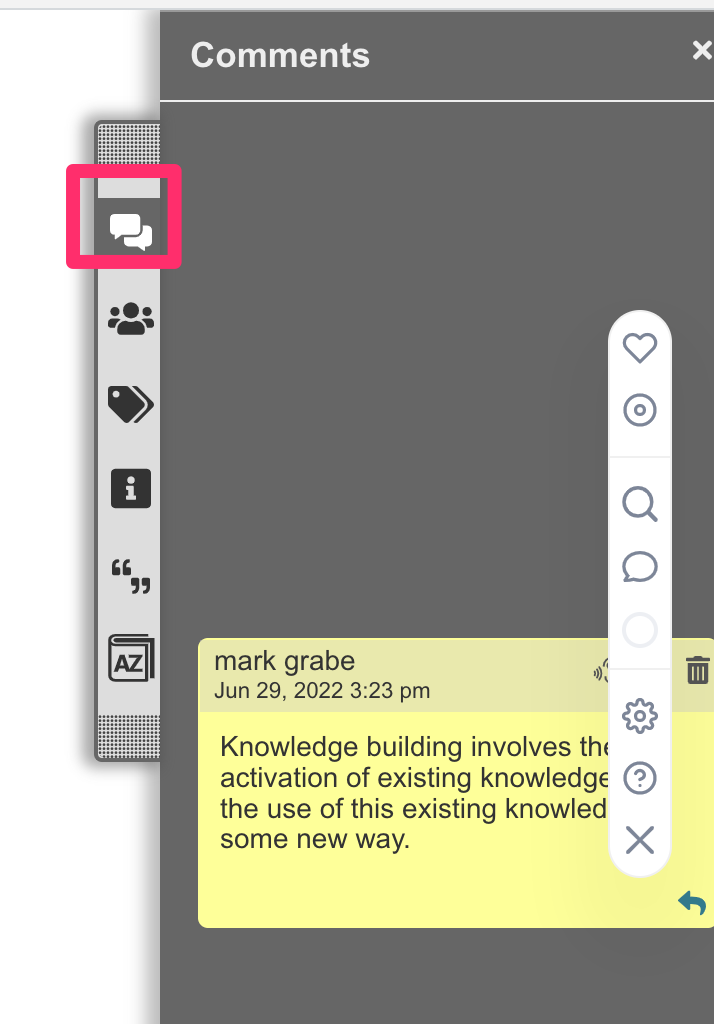

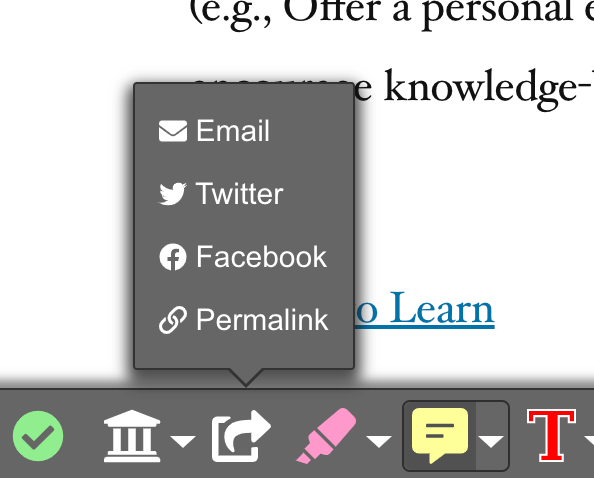

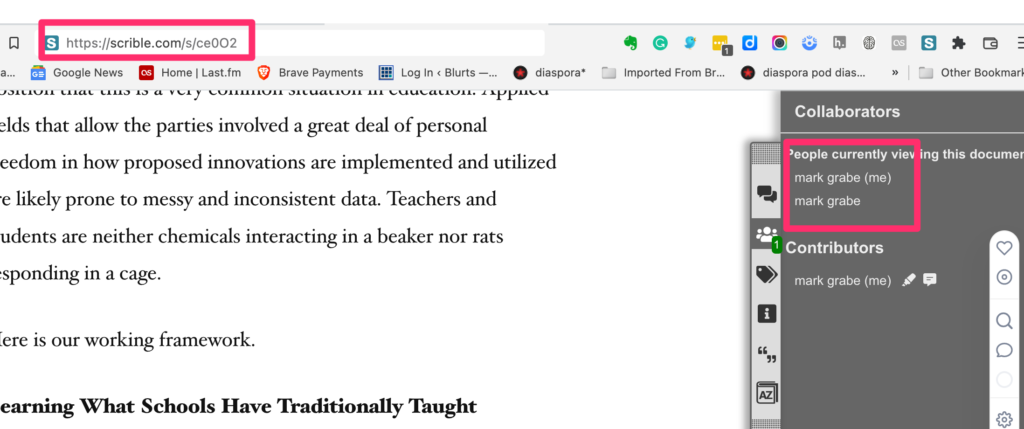

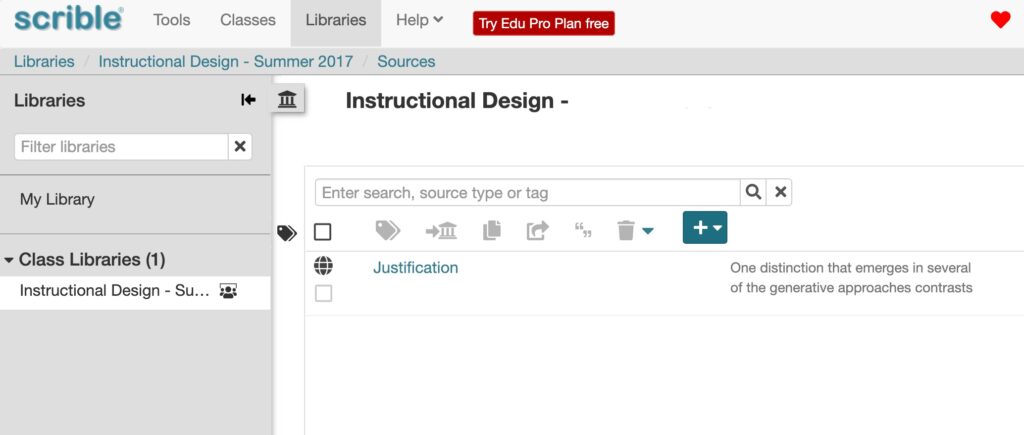

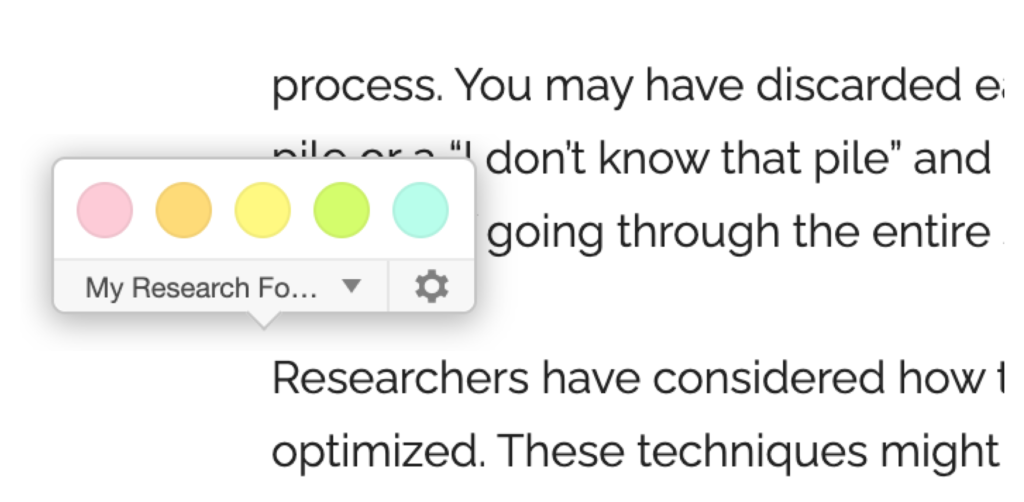

The annotation process in Newsela is very simple and I think that is what you want. When you drag content, you are provided an opportunity to select different colors for highlighting. When you highlight something, you are provided the opportunity to add a note to what has been selected.

Newsela also provides a way to share annotated content. Sharing is available for both educator to students and student to educator. The opportunity to assign an annotation task (e.g., highlight the main ideas in this article) and then submit the completed task for review works through sharing.

Highlighting and note-taking in Newsela are easy to figure out. I encourage educators to take a look and imagine how this capability might be applied. I provide several sources for instructional strategies below and I will try to summarize some of these ideas in a future post.

Sources:

Cohn, J. (2021). Skim, dive, surface: Teaching digital reading. West Virginia University Press.

Lloyd, Z. T., Kim, D., Cox, J. T., Doepker, G. M., & Downey, S. E. (2022). Using the annotating strategy to improve students’ academic achievement in social studies. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning. (early version)

Zywica, J., & Gomez, K. (2008). Annotating to support learning in the content areas: Teaching and learning science. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(2), 155-165.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.