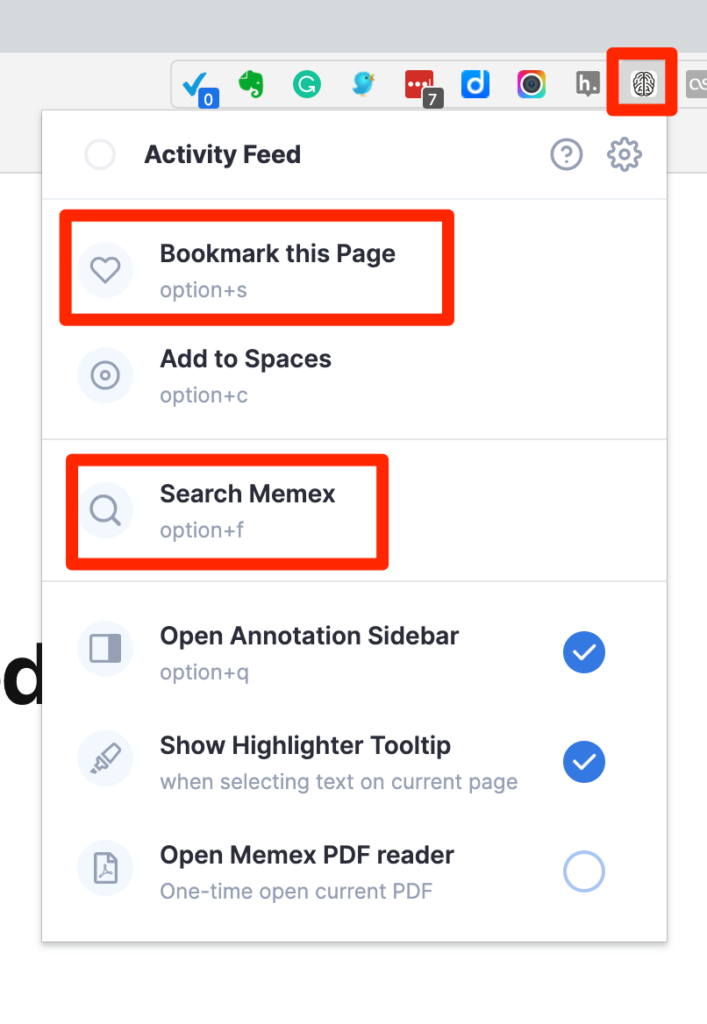

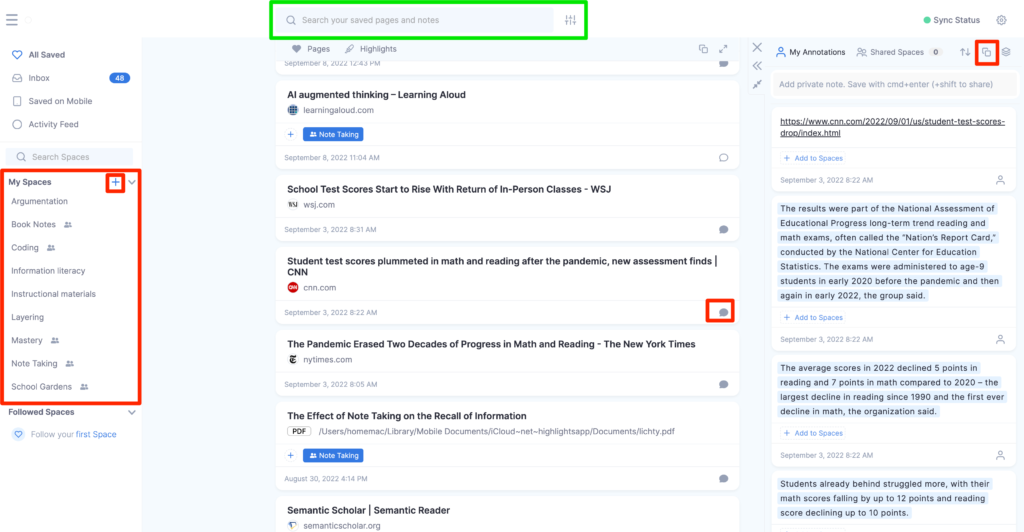

There seems to be a great deal of interest in note-taking. I say this from the perspective of an academic who has been interested in note-taking since the 1970s. The present interest seems to come from two distinct directions. Technology has played a role in both areas of interest. First, there is the focus on personal knowledge management (PKM). This focus recognizes the role knowledge plays in many occupations and proposes that technology can be used to store and organize ideas one encounters so that these ideas can contribute in the future. Associated with this perspective is the idea that technology can be used to build a second brain offloading the less-than-ideal efforts of memory to a technology-enabled environment that can be consulted when ideas and insights generated earlier might be useful.

The second perspective comes from the educational perspective more familiar to me and questions whether notes and annotations related to learning experiences (listening to presentations and reading educational materials) are best processed via paper or screen. As a college learner, you likely took notes in class and highlighted and annotated your textbooks. Now that we carry laptops and tablets to class and read ebooks as an option to traditional textbooks, does it matter if we annotate and take notes on paper or screen?

Those seeking to guide note-taking given these options frequently reference existing research to offer advice. As someone who has reviewed the research in this general area for decades, I sometimes disagree with how the research findings are interpreted. By interpreted I mean that the results of studies are based on the data collected, but more importantly constrained by the methodologies that were used to generate the data and the topics that methodologies best address. Simple conclusions such as “notes taken in a notebook by hand are best” may accurately describe the result of a specific study but may be misleading if generalized to an applied setting that offers a different set of expectations and different options for behavior.

I have been trying to imagine how best to explain the complexities that are involved in translating the note research to applied settings. I have decided I can offer several questions that can be asked of the research and explain why the answers are likely to strongly influence how the results of research should be applied.

Will I be allowed to review my notes?

This may seem a silly question, but I include it because researchers may conduct research not allowing that the notes taken be reviewed because of the question the researchers are asking. Most of us take notes because we want to have something to review before we take an exam or before we take some other action requiring an assist to memory (e.g., what was I going to get at the store). Research on taking notes tends to be based on a theoretical model proposing two hypothetical benefits to taking notes. First, notes offer an external storage mechanism. We can review notes. This use is obvious. Second, taking notes may help us process information when the information is first encountered (while we listen or while we first read). Often called a generative function, the idea is that taking notes is an active way to pay attention or think about ideas as they are encountered and this focus or interpretation may not happen if note-taking was not involved.

In most of the applied settings in which we take notes both generative and external storage benefits are probably involved, but researchers find value in using a methodology that isolates the potential benefits of each benefit. Often, the focus is on differences in how notes might be taken to maximize the generative effect. For example, because most of us can type faster than we can write by hand, notes taken using a keyboard tend to be more complete. This capability to record more complete notes using a keyboard leads to a surprising consequence. If a study compares what is remembered/understood after taking notes using laptops versus paper notebooks and no review is allowed, many results show that retention is better when taking notes by hand. The logic used to explain these results suggests that learners must think more carefully when they can record less information (handwritten notes) and this selectivity results in a more active type of processing generating better understanding/retention.

Some use such results to conclude we should continue taking notes with pen and paper. Educators might not allow students to take notes using a laptop. However, does this really make sense? Most actual applications of note-taking involve the intent to have a quality set of notes to review/study. How often would we take notes and then discard the notes on the way out of the classroom assuming the benefit of the notes has been achieved?

So, when research is offered arguing taking notes on paper is superior to taking notes using a computer, review the methodology to see if participants were allowed to study the notes they took.

Who am I taking notes for?

There may be a better way to phrase this question, but my intent is to draw a distinction that involves who has decided what is important to know and retain. With PKM, notes are intended to serve a future purpose typically determined by the note taker. I take notes because I think the information may be useful in a future writing project. Others might take different notes on the same material because they foresee the notes serving a different purpose.

The research focused on student study behavior involves a different situation. In such situations, the instructor will create some assessment approach and the learner is preparing as best they can for this assessment. They may try to predict what should be emphasized, but they are in a situation in which complete representation of the ideas in the content presented is the best strategy. Hence research that demonstrates a given approach (keyboarding) allows a more complete record, might be the type of research that is of greatest value.

Can I control the pace of the input?

Taking notes from an audio or video presentation and from a static source such as a book or web page have several obvious differences. One that is particularly important is the pace of the input. A static source can be studied at whatever pace the reader applies. A source that changes requires that the viewer/listener keep up.

Human cognition has a built-in bottleneck that is important to recognize. Cognitive researchers refer to this bottleneck as short-term memory or working memory. Working memory has both capacity and duration limits. Translated this means each of us has the capacity to be aware of only so much at one time and what we are aware of will slip from awareness unless we concentrate our attention on this information. Both limitations come into play when the source for information is constantly changing. Activities such as thinking and note-taking both take time and require that we hold what we are thinking about and consume awareness in holding this information. Meanwhile, the input continues to roll along offering new information that is either ignored or substituted for the information that is presently being considered. Perhaps it is fair to conclude that taking notes from a static page and an ongoing lecture exert different demands and require different decisions. When you decide to record a note from a lecture you are risking missing something and this is not the case when you can return to a printed page when you want.

The difference between taking notes from a dynamic and a static source interact with other variables I have already mentioned. For example, if recording notes from a keyboard is easier than with pen and paper, the decision to use a keyboard probably has greater consequences when listening/watching a dynamic input.

Here is one related advantage of tech for note taking many do not realize exists. There are several apps that allow an input to be recorded while notes are being taken (see my review of SoundNote). Such apps link the notes to locations in the recorded sound. When reviewing such notes and encountering something that seems confusing, the linked audio can be replayed offering the note-taker a second chance. Other useful strategies can also be applied. For example, if you know while taking notes you do not understand or missed something you can simply enter a cue in your notes – perhaps ???? – and use this prompt to review the confusing audio at a later time.

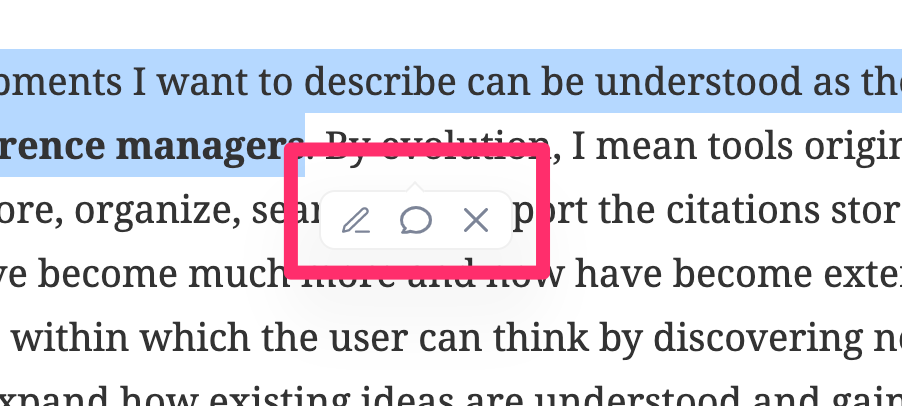

Is annotation of the source allowed?

This question applies to text inputs and typically to K12 settings. Often learners in this setting are not allowed to annotate/highlight the content they are asked to read. You are not allowed to mark up your textbook. Magically when you get to college and purchase your textbooks, study tactics are allowed you did not practice in high school.

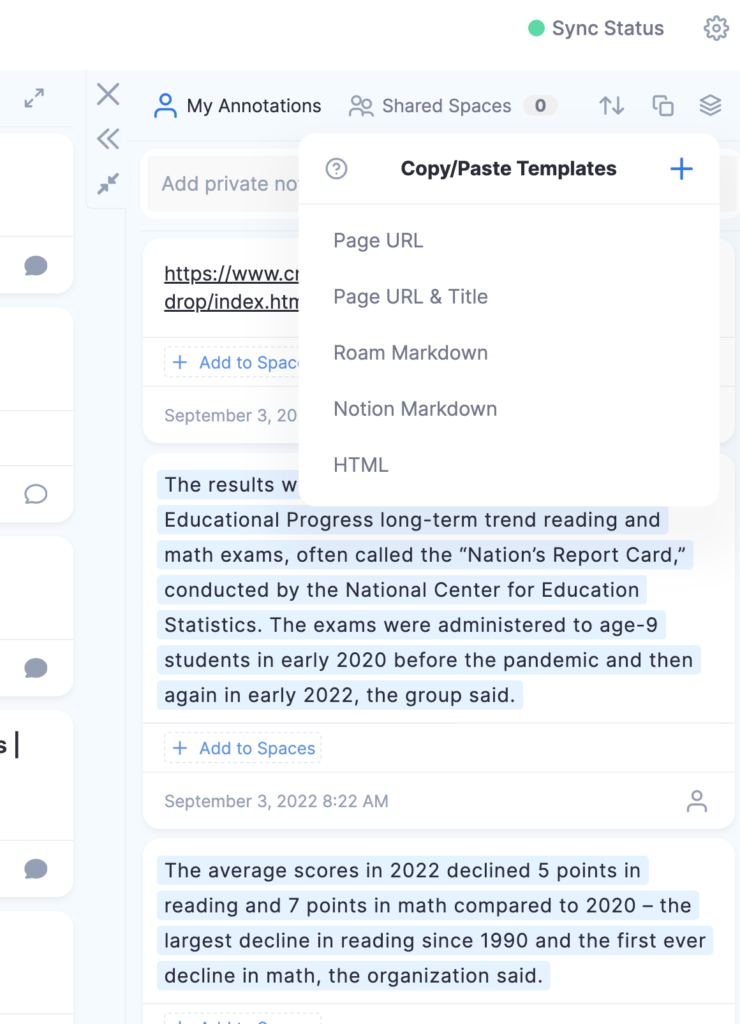

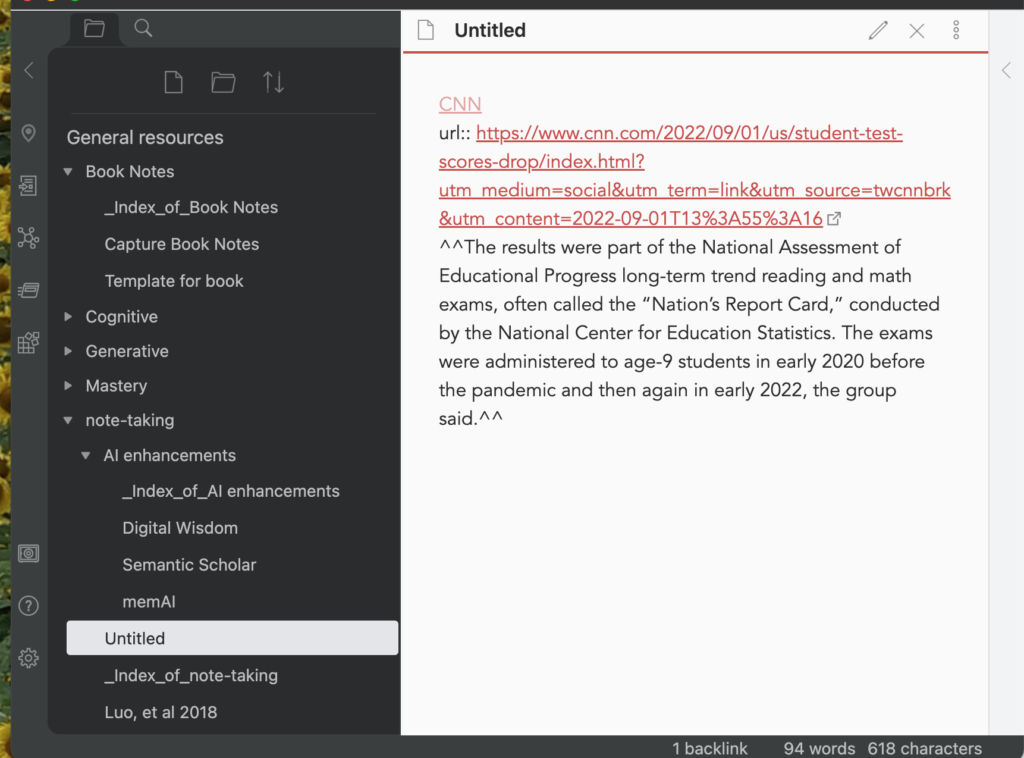

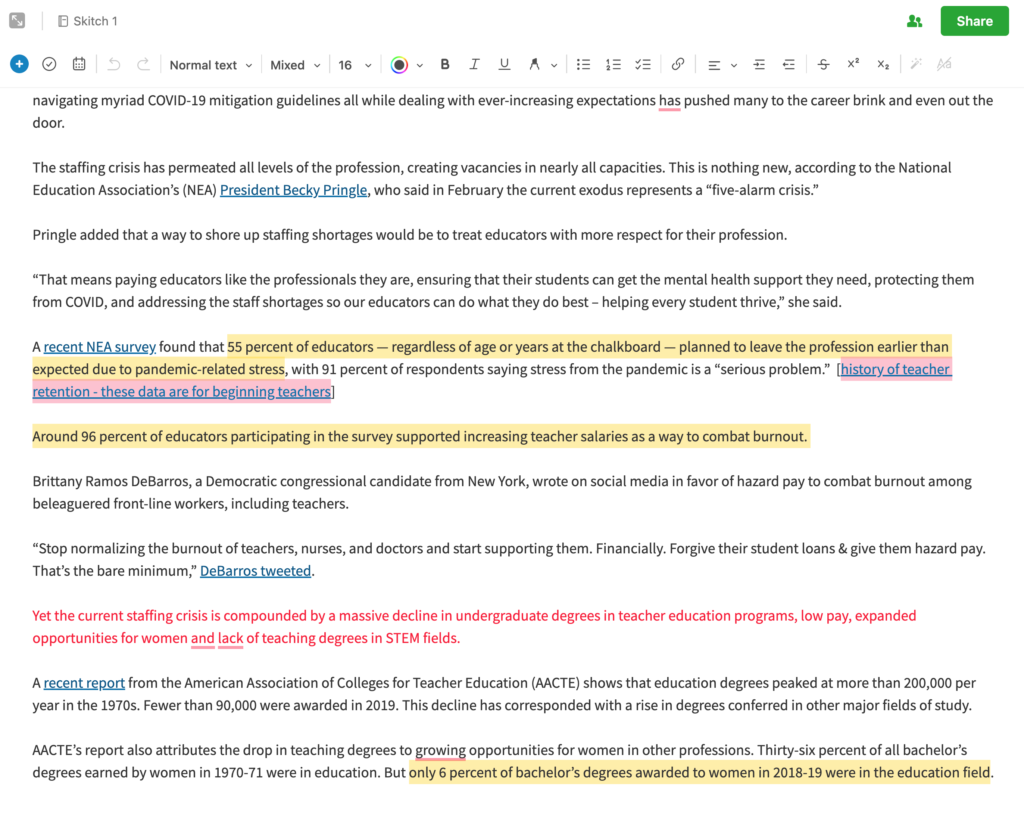

Again, technology changes this situation at all levels of education. eBooks can be annotated and highlighted because the ebook itself is not passed on from class to class. The eBook environment also allows a form of note-taking that is more flexible than that which can be added in the margins of a page. The amount of information that can be included in a note is greater and the note itself may contain elements such as web links that are not realistic additions in the margins.

Is there an activity assumed to happen between recording and application?

One final distinction between the types of note-taking that happen in experiments and the way notes can be used in applied situations concerns when and how frequently notes are reviewed after creation. Study skill experts sometimes recommend both multiple reviews of the notes taken and reviews designed to accomplish specific goals. For example, if a student reviews the notes taken soon after the initial exposure to the information that was presented, the student typically still has a memory for the context of the presentation and content not necessarily recorded in notes taken during class. Reviewing notes at this point in time allows an upgrade to the notes and the review itself positively impacts achievement when understanding must be demonstrated.

There are related opportunities when note use is understood to allow more than simple review. For example, there has been great interest in collaborative notes or expert notes as a way to enhance the notes taken by individuals. Efforts by those developing technology-enhanced approaches to PKM are even exploring the use of artificial intelligence to identify notes on similar concepts generated by others.

Conclusion

My goal in identifying the issues that appear above is to help readers understand that the note-taking and external knowledge representation field is more complicated and interesting than one might assume. It is easy to be misled if one seizes on the conclusions of single experiments if one does not carefully analyze the methodology that was used to generate the data leading to the conclusions of the researchers.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.