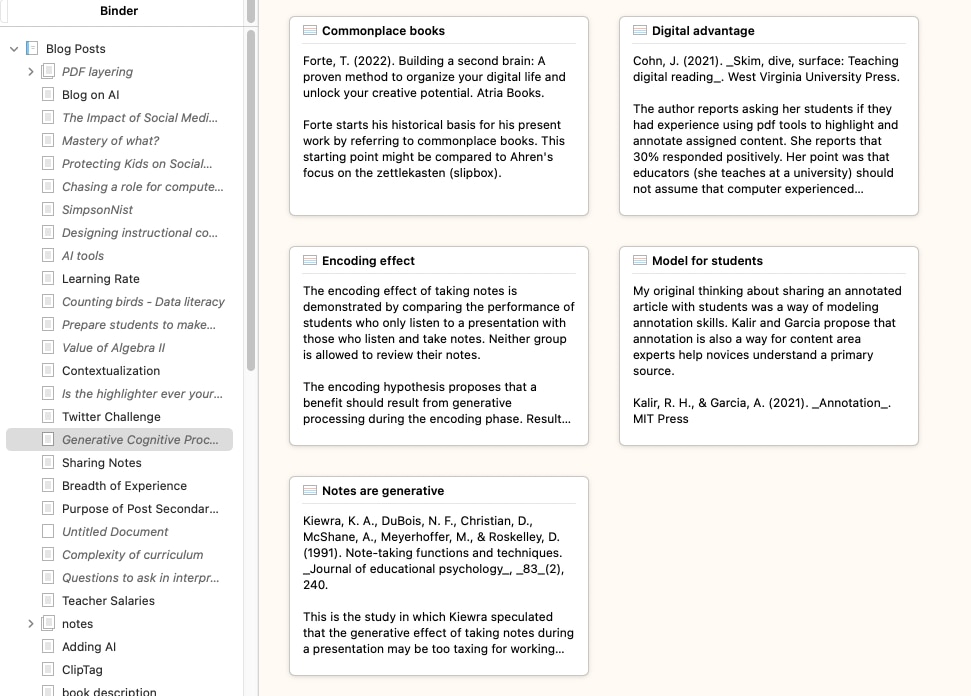

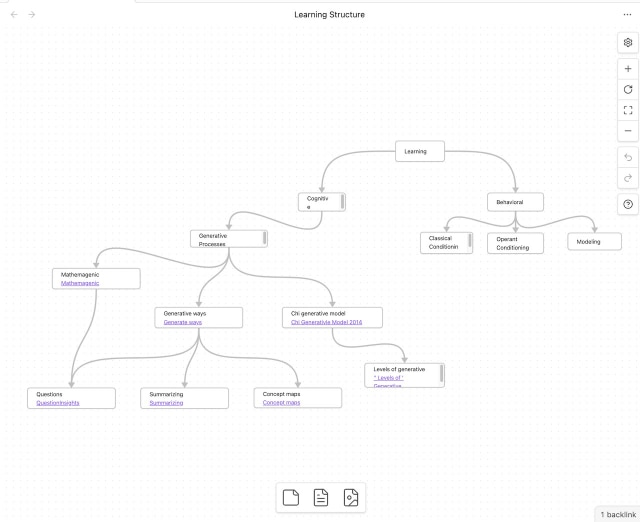

My recent focus on losing an author’s perspective when consuming AI-generated content, particularly the AI response now preceding the typical hits generated by a search query, has encouraged a personal exploration of what might be a middle ground. I frequently use AI tools to chat with the notes and highlights I have generated in reading hundreds of journal articles and books. This body of content has a perspective of sorts because the notes I generate and the content I identify through highlighting reflect my personal way of viewing my field and represent ideas that both support and oppose scientific concepts and theories important to these topics. Any researcher who has relied on the accumulation of relevant articles over the years and makes use of PDFs rather than paper could do a similar thing to make extended use the content they have accumulated over the years. This accumulated body of content seems a great example of what the personal knowledge management advocates describe as a second brain.

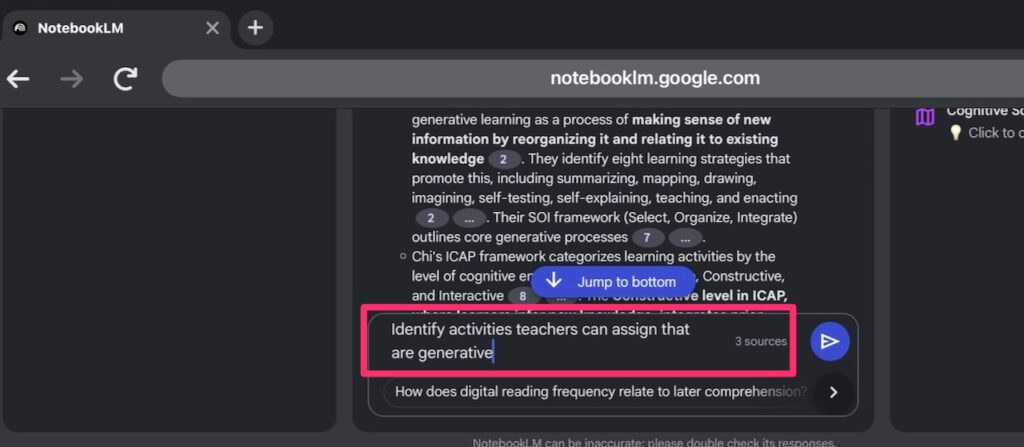

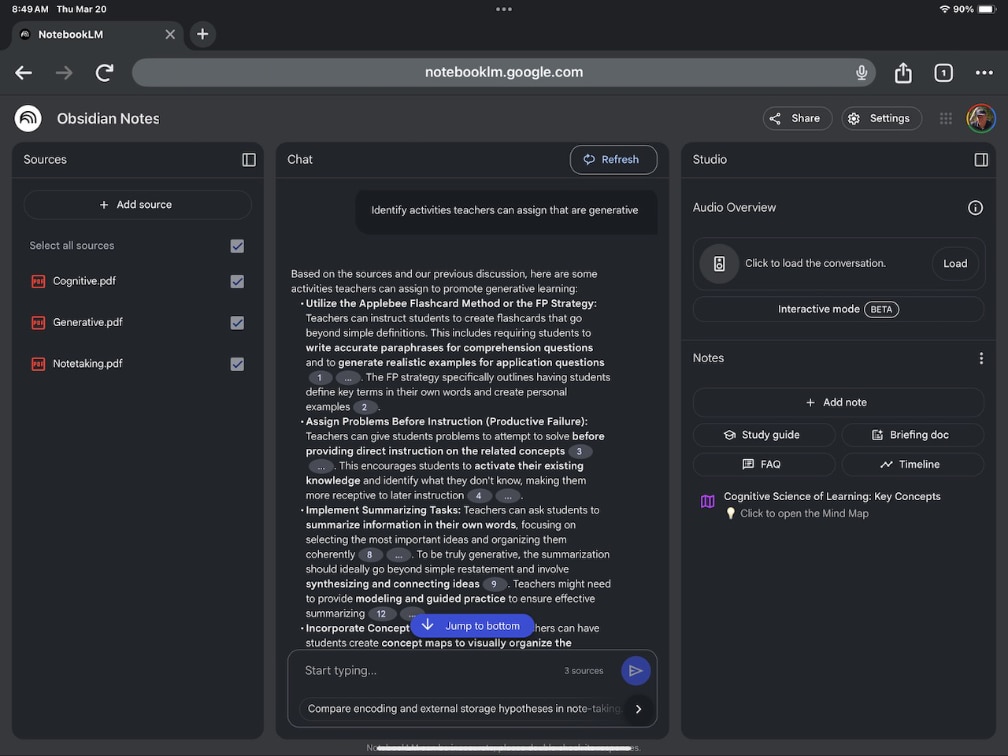

Here, then, is what I believe to be an interesting question. Do AI chats with personally curated content provide different insights than a similar AI chat without this curated focus? Perhaps a more concrete example would be a better way to communicate my issue. So, I have the highlights and notes I have accumulated from years of reading in a designated area (e.g., educational applications of cognitive psychology), and I can chat with this content using identifiable services (e.g., NotebookLM). Would the reply to a prompt applied under these circumstances yield different insights than the same prompt applied using an AI tool not focused on a designated body of content (e.g., Perplexity)?

At first, this might seem a silly comparison. Certainly, one could find a biased assortment of resources taking a common flawed view on a topic, and then show that AI limited to consolidating this content would yield different prompt replies than similar prompts asked of an unfocused AI tool. But this does not seem to be what those building a second brain think they are doing. They would likely be offended by the suggestion that their efforts were for naught, and AI queries would yield more accurate information. They would probably suggest they are doing exactly the opposite. They are using their expertise to identify high-quality sources, and their notes would address both the strengths and weaknesses of the sources they curate. I am not certain the outcome of my proposed comparison is obvious.

My Test Case

I write a lot about study behavior and have found the controversy involving whether learners are better off reading and taking notes using paper or digital content of some interest. While many researchers suggest paper is superior, my personal experiences and focus on the benefits of previous learning experiences over time, see a unique value in digital processing. Simply put, highlights and annotations saved and organized offer advantages over a year or 50 years later that most would find difficult to replicate with paper. Even over short periods, studying is more than simple review, and digital tools offer unique opportunities for “post processing”.

The specifics here are important only if the type of information generated in pursuit of the information I encounter would change as a function of how I might use AI. I provide the background material because the topic could interact with the different uses of AI I identify in ways I cannot anticipate. Part of what I propose is that others with different collections of digital content might replicate the test I am applying to their own material and share their observations. There are so many uncontrolled variables I assume that while this is an interesting issue, personal preference will always be the deciding factor. Variations in topic, tool, and prompt could result in different conclusions.

The Prompt I used follows. The variation of the prompt I used when engaging a non-focused use of AI simply eliminated the phrase “Using my notes and highlights”.

Prompt: Using my notes and highlights, write a 400 word blog post comparing the advantages and disadvantages of reading and taking notes from paper and digital devices.

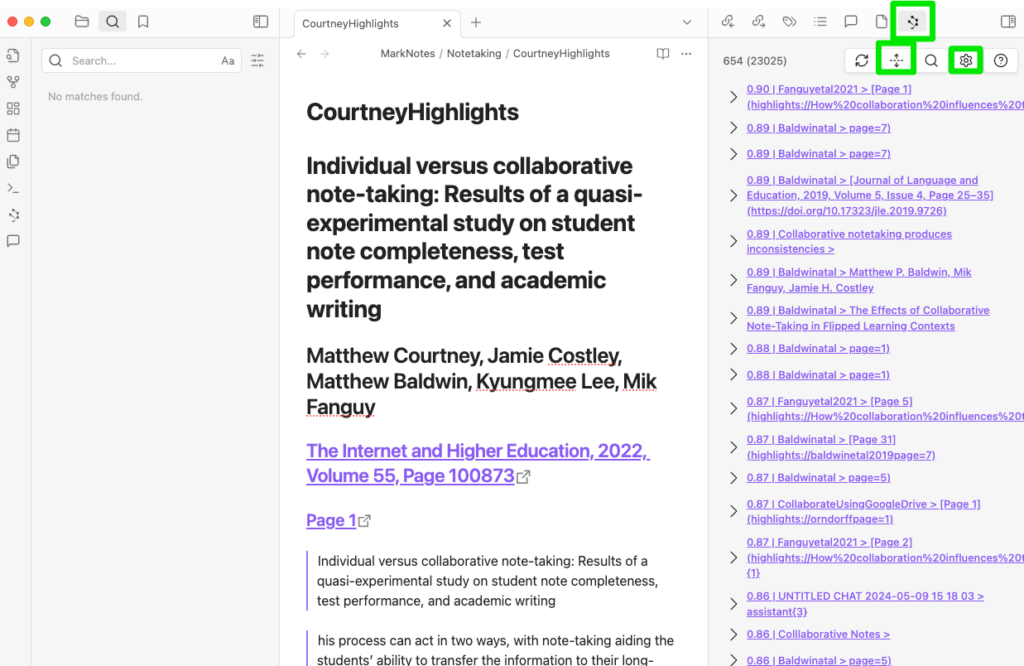

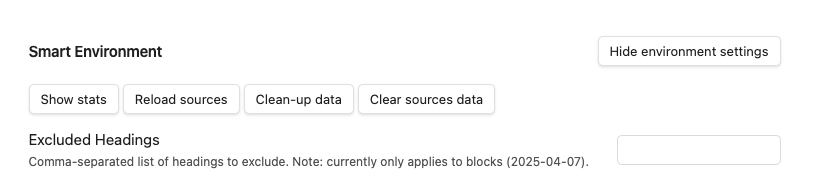

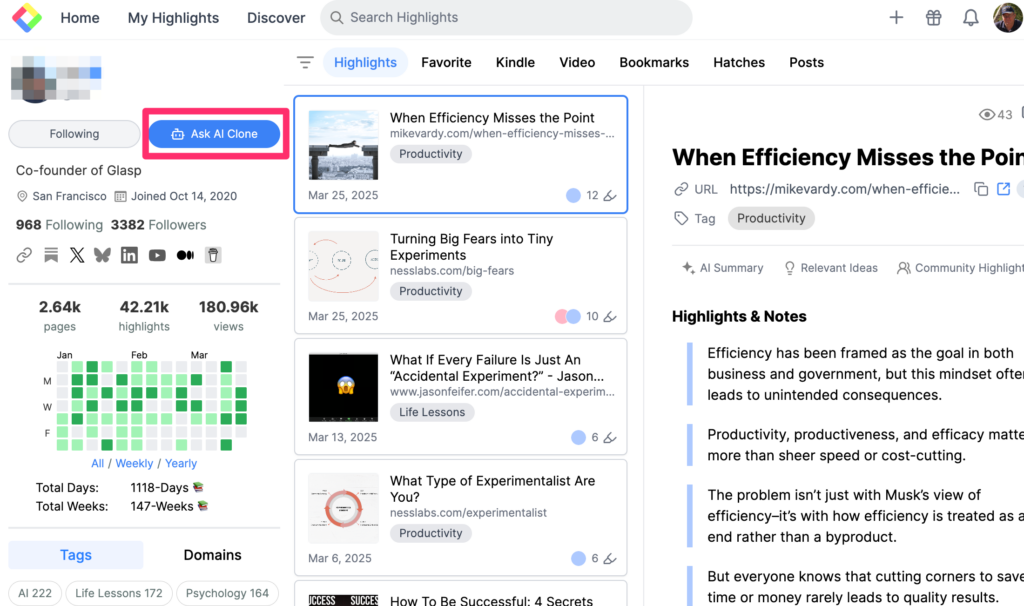

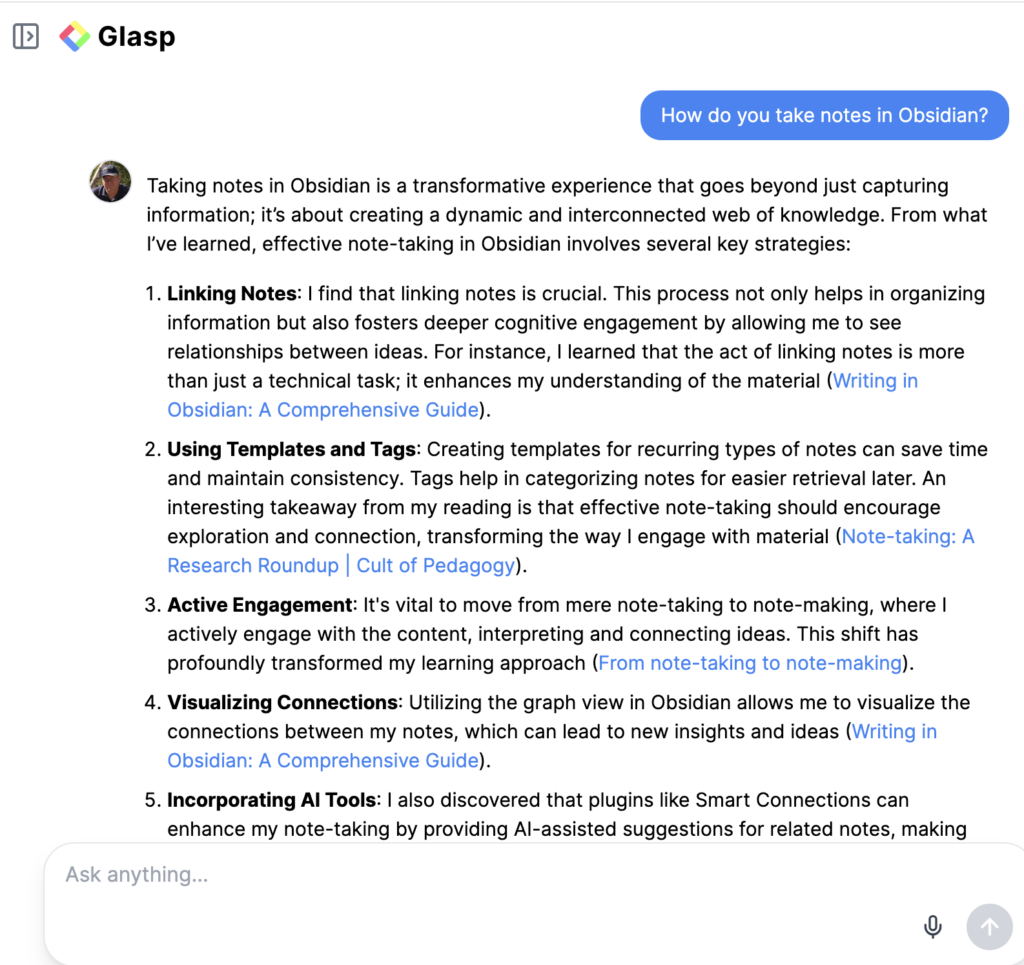

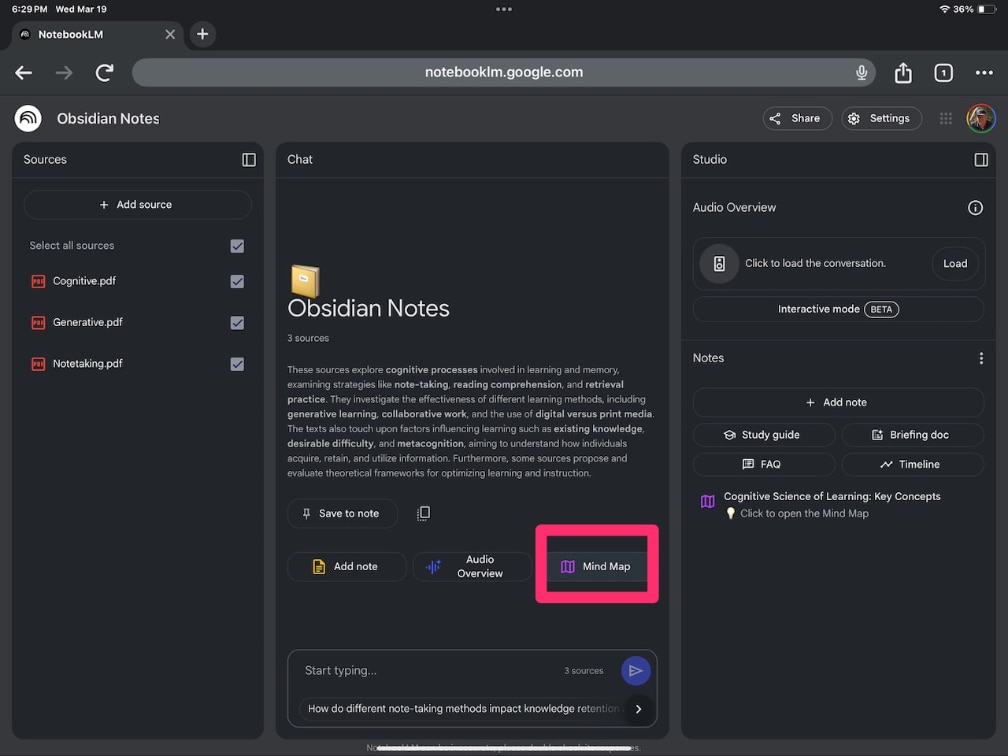

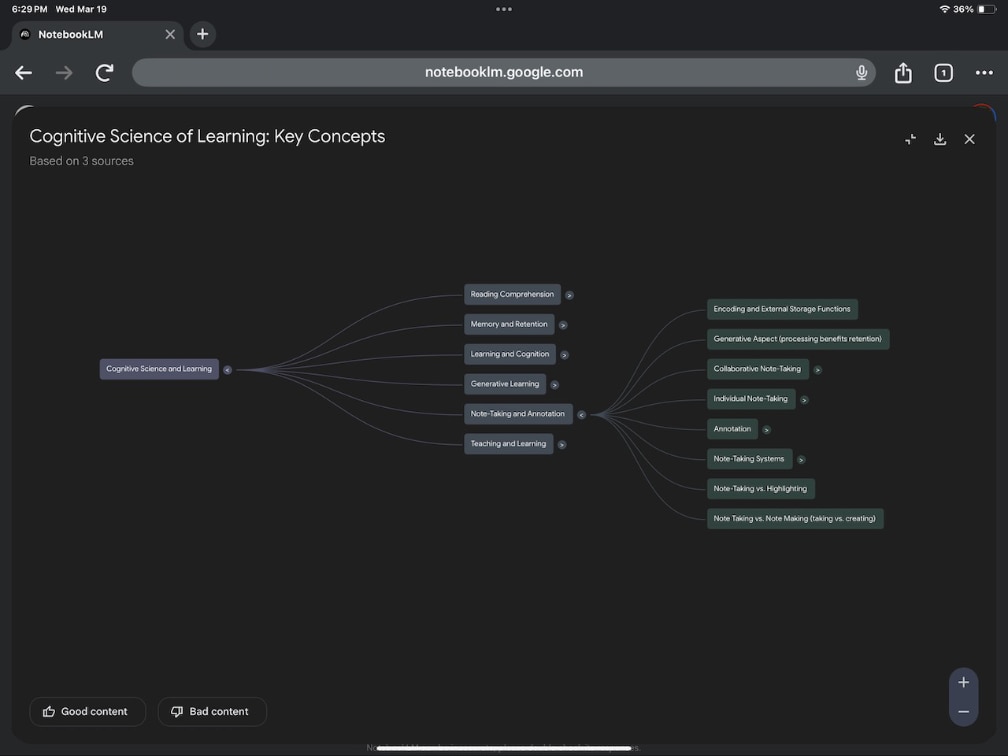

I used the directed prompt with Mem.AI, NotebookLM, and Smart Connections (Obsidian plugin). Perplexity was used as the nondirected AI tool. I will offer my observations first and provide the full prompt responses at the end as Appendices.

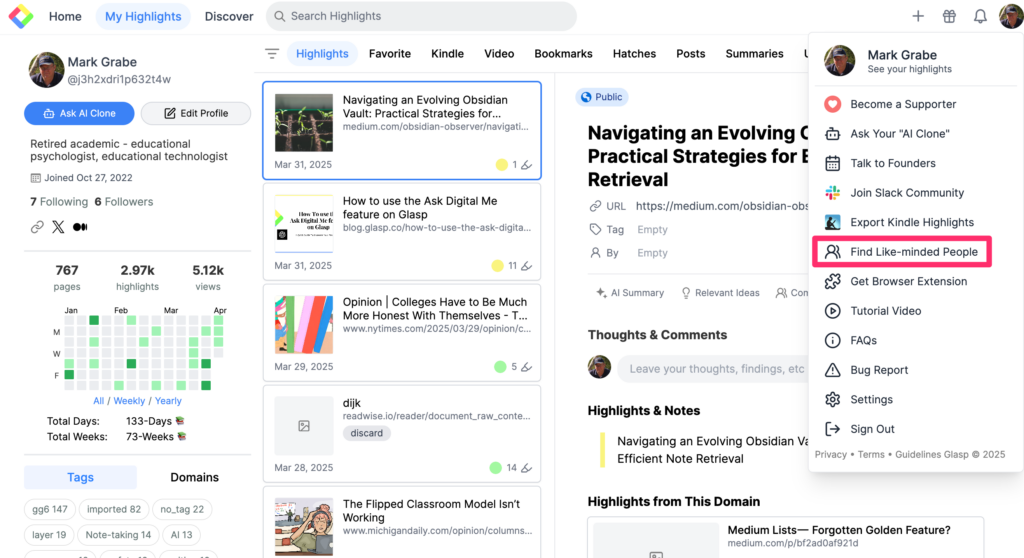

Sources – Perplexity is unique in comparison to other chat tools in that it provides specific sources for comments it generates. These tend to be what I would call secondary sources (see list following the Perplexity example). In contrast, see the sources in the Mem.AI responses. The names that appear are a crude version of the citation method academics use to reference journal articles and books (which were the sources I highlighted and annotated). One way to think about this may be that Perplexity is accessing the summaries generated by various individuals who have read primary sources, while Mem is accessing my personal summaries of similar sources. If identifying primary sources is important, it is easier to do this when you can show what these sources were.

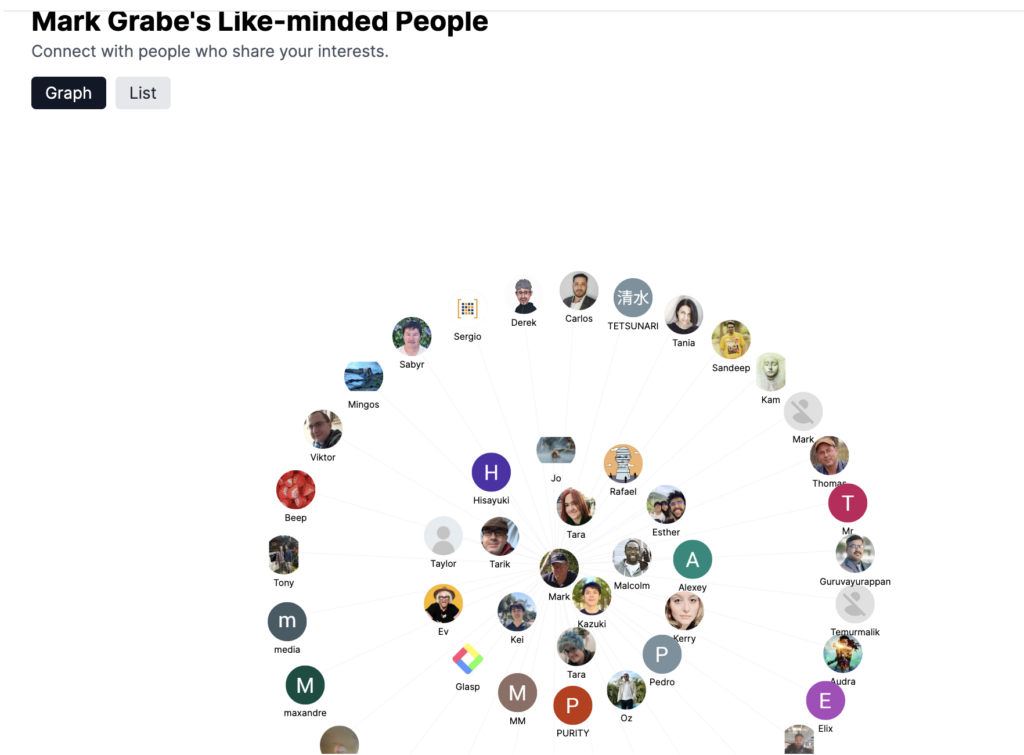

Identification of unique insights – It would seem that an AI analysis based on specific notes, highlighting, and source selection would generate an output more useful for tasks you want to pursue. While obvious if the content of interest was selected with a task in mind and based on a small amount of material, this is not the way a “second brain” is built. The hundreds of sources I have collected represent a wide range of topics in my field. Specific topics of interest emerge within this process of more general learning, and part of the assumption in using a second brain is that the broader background will reveal connections that may not have been anticipated. The hope is that the application of AI, rather than basic searching, will help surface such connections.

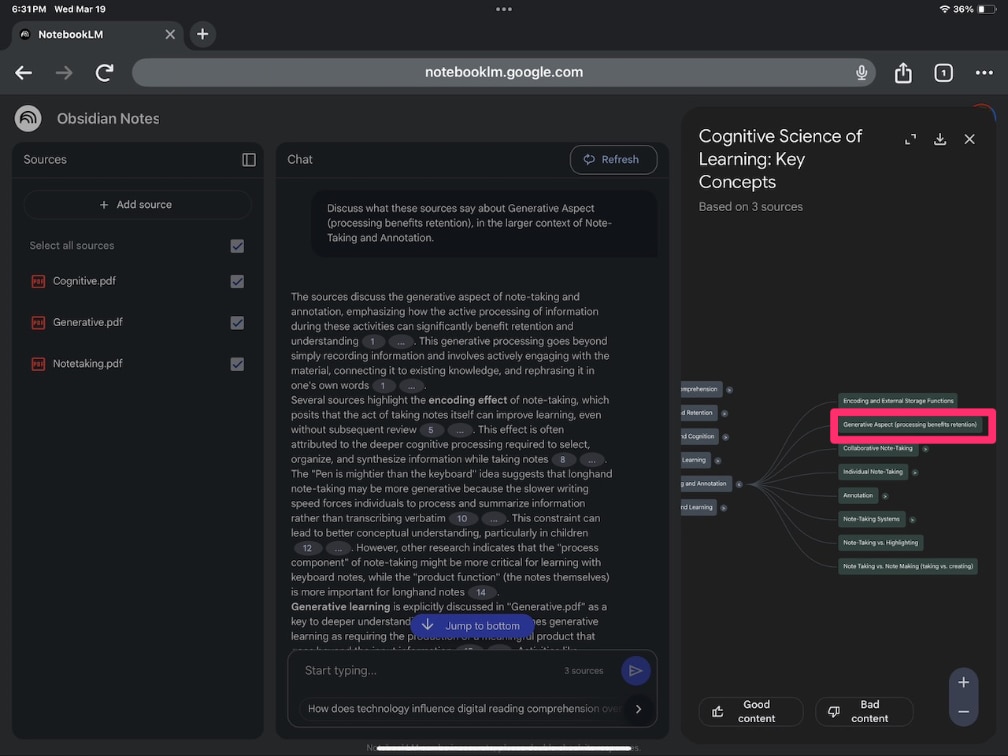

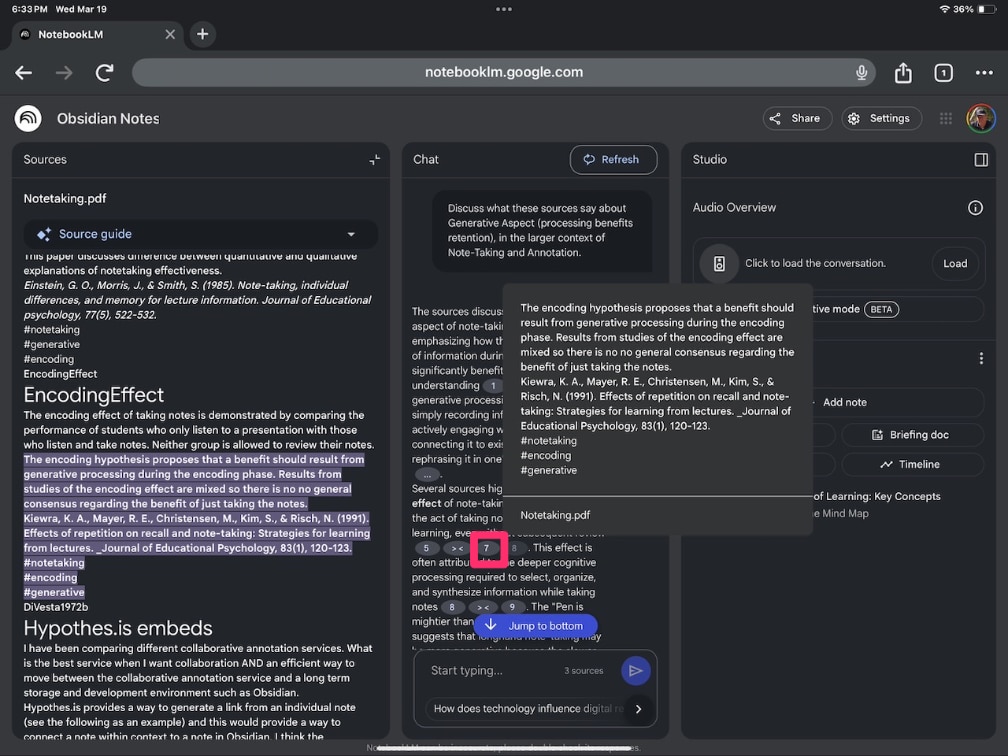

With the exception of the sources cited, much of the information in the two types of searches was similar. Perhaps asking for a 400-word blog post as an outlet was not the best way to reveal subtle differences. I will direct your attention to sections I have highlighted in the NotebookLM and Perplexity prompt responses. Both NotebookLM and Perplexity provide citations that do not appear when copying the text. Because I was looking for comments related to the use of content over time, I was paying attention to any mention of searching or other mentions of delayed activity. The Perplexity response did not offer a citation. The NotebookLM output mentioned export, organization, and search. In addition, there were multiple citations, and the linked citations identified notes and highlights in the digital form.

Summary

AI tools with various capabilities are now available. For those of us who read digitally, we have the opportunity to export highlights and annotations that can be stored over time. AI can be used to chat with this stored content. My interest here was an attempt to determine if there was a unique value in applying AI to such content in comparison to asking questions of AI without this targeting of curated information.

I doubt the effort I describe here would convince anyone to change their existing strategy, but my hope is that I have offered an approach they might try to explore the options that are available.

************

Appendices

Mem.ai

The debate between reading and taking notes on paper versus digital devices is a nuanced one, with research highlighting various advantages and disadvantages for each medium. While digital tools offer convenience and speed, traditional paper methods often promote deeper cognitive engagement.

Advantages of Digital Reading and Notetaking

Digital devices offer several benefits. For instance, digital note-takers tend to record more content, including more verbatim lecture strings, due to faster typing speeds compared to handwriting Luo et al 2018. This increased volume of notes can be beneficial for later review, especially when notes are not immediately studied Luo et al 2018. Digital platforms also facilitate collaborative note-taking, allowing students to share the cognitive load and potentially create more complete notes Courtneyetal2022. Furthermore, digital tools can offer features like multimedia integration and online research capabilities, enriching the learning experience Yamac et al 2020. For example, digital writing instruction with tablets has been shown to improve writing performance and knowledge in primary school students, partly due to features like class blogs and multimedia components Yamac et al 2020.

Disadvantages of Digital Reading and Notetaking

Despite the advantages, digital reading and note-taking come with notable drawbacks. A significant concern is the potential for distraction. Studies suggest that the perceived advantage of longhand note-taking in some research may be attributed to the distractions inherent in digital devices, such as web surfing and social media Voyer 2022 summary. This can lead to shallower processing of information SingerAlexander2017b. Research indicates a “screen inferiority” effect, where reading comprehension can be lower on digital devices, particularly for informational texts and under time pressure Delgado2018. This effect has even been observed to increase over time Delgado et al 2018. The lack of physical cues, like the feel of pages, in digital reading can also hinder the formation of a mental map of the text, impacting comprehension of chronology and temporality Mangen et al 2019.

Advantages of Paper Reading and Notetaking

Paper-based methods often foster deeper engagement and better retention. Handwriting, being slower than typing, forces individuals to process and summarize information, leading to a more generative encoding of knowledge MuellerOppenheimer2014. This deeper processing can result in better performance on conceptual questions

MuellerOppenheimer2014. The physical act of writing and the tactile feedback from paper contribute to a stronger mental representation of the material Mangen et al 2019. For instance, studies have shown that paper readers are better at recalling “other relevant information” and performing better on questions related to key points SingerAlexander2017b.

Disadvantages of Paper Reading and Notetaking

While beneficial for deep processing, paper note-taking can be less efficient in terms of speed and volume compared to digital methods Luo et al 2018. It also lacks the inherent searchability and organizational capabilities of digital notes, which can make retrieval and restructuring of information more challenging SmartWisdom. Converting highlights from paper to more elaborate notes can also be a more cumbersome process Highlighting&fleeting.

In conclusion, the optimal choice between paper and digital depends on the specific learning goal and context. For tasks requiring deep comprehension and conceptual understanding, paper often holds an advantage. However, for efficiency, volume, and collaborative efforts, digital tools offer compelling benefits, provided distractions are managed effectively.

************

NotebookLM

Here’s a look at the advantages and disadvantages of reading and taking notes using paper versus digital devices, drawing from the sources provided:

The rise of digital devices has shifted how many people read and take notes. However, research comparing reading from paper and screens reveals a complex picture, with nuances depending on the text type, reader’s age, and even the specific device used. Several meta-analyses indicate a general advantage for reading comprehension when reading from paper compared to screens, particularly for informational texts. This paper advantage has even been found to increase over time. However, this difference is often not seen with narrative texts, and studies comparing reading on tablets specifically have sometimes found smaller or no significant differences compared to print.

When it comes to note-taking, there’s also ongoing debate about the best method. Some studies comparing handwriting and typing notes have found a benefit for handwriting notes, particularly for understanding concepts. This has been attributed to the slower speed of handwriting, which may encourage more summarization and paraphrasing rather than simply transcribing verbatim, leading to deeper cognitive processing. However, other research and meta-analyses have found inconsistent results or no significant overall difference between handwritten and typed notes. Some studies suggest that typing can lead to more complete notes, and note completeness can be related to better performance.

Digital tools offer powerful affordances for reading and note-taking, such as the ease of highlighting and adding annotations directly to the text. Digital notes and highlights can be easily exported, organized, and searched later. Digital environments also facilitate collaborative annotation and note-taking. However, digital environments can also present challenges. They may be more prone to distractions, and frequent use of digital media, particularly for quick interactions with short texts (like social media), may contribute to the development of shallow reading habits like scanning and skimming. Some online content may also have lower linguistic quality.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of reading and note-taking, whether on paper or digitally, depends significantly on the strategies and cognitive processes employed by the reader. While paper might offer some advantages for deep comprehension of informational texts and handwriting for conceptual processing, digital tools provide powerful functionalities for capturing, organizing, and retrieving information, as well as facilitating collaboration. Focusing on how one engages with the material and utilizes the tools, rather than just the tool itself, is likely key to effective learning.

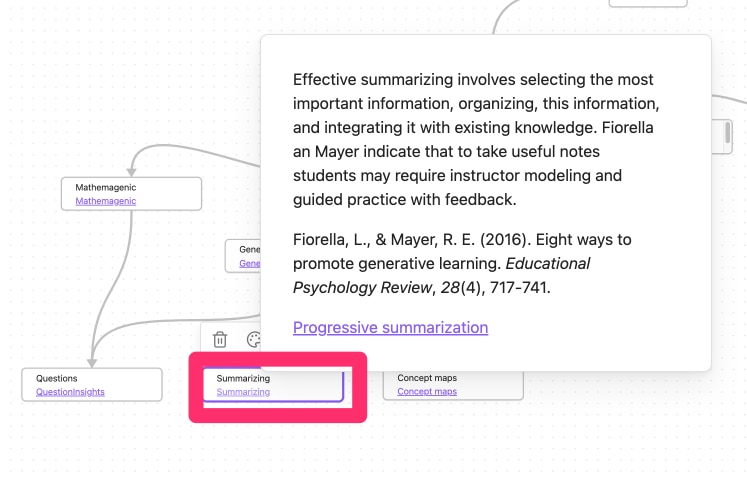

The following is a screen capture of the original view of the highlighted section described above.

****************************

Prompt: Write a 400 word blog post comparing the advantages and disadvantages of reading and taking notes from paper and digital devices.

From: Perplexity

Comparing Reading and Note-Taking: Paper vs. Digital Devices

Choosing between paper and digital devices for reading and note-taking is a personal decision shaped by convenience, effectiveness, and lifestyle. Both formats offer distinct advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages of Paper

- Better Comprehension and Retention: Studies show reading from paper leads to higher comprehension and test scores. Students who read print books outperform those who read digitally, and handwritten notes often result in better memory retention compared to typing[1][6].

- Fewer Distractions: Paper books and notes keep things simple—no pop-ups, notifications, or temptations to multitask, which helps maintain focus[1][6].

- Emotional Connection: Many readers find a deeper emotional bond with physical books, appreciating the tactile experience and the satisfaction of seeing their progress[1].

- No Power Needed: Paper never runs out of battery and is always ready to use[1][6].

Disadvantages of Paper

- Storage and Portability: Physical books and notes take up space, can be heavy, and are cumbersome to transport, especially when traveling or moving[5].

- Accessibility: Finding a specific book or note can be time-consuming, and you must visit libraries or bookstores for new material[5].

- Environmental Impact: Paper production contributes to deforestation and environmental harm[5].

- Vulnerability: Paper can be easily lost, damaged by water or fire, and is harder to back up[5][6].

Advantages of Digital Devices

- Convenience and Accessibility: Digital libraries offer instant access to thousands of titles and notes, all stored on a single device. Searching for information is quick and efficient[3][4].

- Eco-Friendly: Digital reading and note-taking reduce paper usage and environmental impact[3][4].

- Interactivity and Multimedia: eBooks and digital notes can include videos, images, and interactive elements, making learning more engaging[3][4].

- Collaboration and Organization: Digital notes are easy to organize, search, and share. Real-time collaboration and version control are possible, which is ideal for group work[4].

- Accessibility Features: Text-to-speech and adjustable font sizes make digital content more accessible to people with different needs[3].

Disadvantages of Digital Devices

- Distractions: Devices can tempt users with games, notifications, and other apps, reducing focus[6].

- Lower Retention: Typing notes can lead to lower retention compared to handwriting, as it often encourages verbatim transcription without deeper processing[6].

- Dependence on Power: Devices need batteries and charging, which can be limiting in certain situations[6].

- Cost: Digital devices are more expensive upfront than basic paper and pen[6].

Conclusion

Paper excels in comprehension, retention, and simplicity, while digital devices shine in convenience, organization, and collaboration. The best choice depends on your priorities—whether you value focus and memory or accessibility and efficiency. Many find a hybrid approach, using both formats as needed, offers the best of both worlds.

Sources

[1] The benefits of printed books – Junior Library Guild https://www.juniorlibraryguild.com/blog/post/the-benefits-of-printed-books

[2] Benefits of Notetaking? | Student Skills Workshops https://sites.austincc.edu/student-skills-workshops/taking-effective-notes/benefits-of-notetaking/

[3] Top 7 Benefits of Digital Reading in 2025 – Kitaboo https://kitaboo.com/what-is-digital-reading/

[4] 6 advantages of digital note-taking: unleash your productivity https://beingpaperless.com/unleash-your-productivity-6-advantages-of-digital-note-taking/

[5] Paper Books Vs. Ebooks https://www.doradolist.com/blog/paper-book-vs-ebook/

[6] Typing vs. Writing: The Pros and Cons of Both Note-Taking Methods https://titantimes.live/2025/02/19/typing-vs-writing-the-pros-and-cons-of-both-note-taking-methods/

[7] Digital reading: Pros and cons of reading on devices – tablets & e … https://teachinginhighered.com/2017/09/11/digital-reading/

[8] Taking Digital Notes: The Pros, Cons, and Best Practices – Ask.com https://www.ask.com/news/taking-digital-notes-pros-cons-best-practices

[9] Evidence increases for reading on paper instead of screens https://hechingerreport.org/evidence-increases-for-reading-on-paper-instead-of-screens/

[10] Benefit of Handwritten vs. Digital Note Taking https://www.mrsblackwell.com/journal/note-taking

[11] Will you learn better from reading on screen or on paper? https://www.snexplores.org/article/learn-comprehension-reading-digital-screen-paper

[12] Unlocking the Brain: the Cognitive Benefits of Digital Note-Taking for … https://www.marshmallowchallenge.com/blog/unlocking-the-brain-the-cognitive-benefits-of-digital-note-taking-for-students-sounds-great/

[13] Advantages And Drawbacks Of Both Paper And Pixel Books https://tracycooperposey.com/paper-and-pixel-books/

[14] Digital Notes vs. Paper Notes: The Pros and Cons – SchoolHabits https://schoolhabits.com/digital-notes-vs-paper-notes-the-pros-and-cons/

[15] What are Top Pros and Cons of Online Reading in 2025? – Kitaboo https://kitaboo.com/pros-and-cons-of-online-reading/

[16] Digital vs. Handwritten Notes: Pros and Cons for Professionals https://leadavid.com/digital-vs-handwritten-notes-pros-cons/

[17] Reading On Screens vs Paper: Which Is Better? – Unplugged https://unplugged.rest/blog/reading-on-screen-or-print-which-is-better

[18] Paper vs. Screen: Note-taking at Dartmouth https://www.thedartmouth.com/article/2023/10/paper-vs-screen-note-taking-at-dartmouth

[19] The Advantages of Using a Digital Note Taking App – Box Blog https://blog.box.com/advantages-of-using-a-digital-note-taking-app

[20] Do Students Learn More by Reading From Paper or Screens? – EWU https://online.ewu.edu/degrees/education/med/reading-literacy/reading-from-paper-or-screens/

[21] Pros and Cons of Typed, Digitally Handwritten, and Paper Notes https://guts.wisc.edu/2020/11/19/pros-and-cons-of-typed-digitally-handwritten-and-paper-notes/

[22] Pros and Cons of eBooks: Is Digital Reading Right for You? https://www.wrightbookassociates.co.uk/blog/pros-and-cons-of-ebooks/

[23] Truth about Digital Note Taking vs Paper Notes (PROS/CONS) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nw4Z2cwm30

[24] PROOF POINTS: Paper books linked to stronger readers in an … https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-paper-books-linked-to-stronger-readers-in-an-international-study/

[25] [PDF] Reading on paper and screens: advantages, disadvantages, and … https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f5d3/be4309ea16cede980900c13e65ac48aad6d3.pdf

[26] Pros and Cons of Digital vs. Traditional College Textbooks https://www.honorsociety.org/articles/pros-and-cons-digital-vs-traditional-college-textbooks

[27] Reading on Screens Worsens Comprehension for Younger … https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/reading-on-screens-worsens-comprehension-for-younger-students-what-can-teachers-do/2024/01

[28] 7 Scientific Benefits of Reading Printed Books for Better Brain Health … https://www.howlifeunfolds.com/learning-education/7-scientific-benefits-reading-printed-books

[29] Evidence increases for reading on paper instead of screens: Most … https://www.reddit.com/r/books/comments/n3uc66/evidence_increases_for_reading_on_paper_instead/

[30] 10 Benefits of Reading Print Books, According to Science https://www.realsimple.com/health/preventative-health/benefits-of-reading-real-books

[31] The important thing is to read. Advantages of digital reading https://richmondsolution.com/en/ventajas-lectura-digital/

[32] Digital reading: benefit or risk for child literacy? https://school-education.ec.europa.eu/en/discover/news/digital-reading-benefit-risk

[33] Turning the Page: What Research Indicates About Print vs. Digital … https://oej.scholasticahq.com/article/125437-turning-the-page-what-research-indicates-about-print-vs-digital-reading

[34] E-books vs Printed Books: The Disadvantages of E-books https://web.4hatteras.com/hatteras-news/e-books-vs-printed-books-the-disadvantages-of-e-books

[35] The benefits and drawbacks of reading digitally https://webbcanyonchronicle.com/9378/scienceandtechnology/the-benefits-and-drawbacks-of-reading-digitally/

*****

7 total views

You must be logged in to post a comment.