I have become fascinated with what I now call linear narrative chains (Hays and colleagues, 2008). The phrase is appropriately descriptive in how we experience life including reading and listening to lectures and explains why reprocessing such inputs is important to understanding and learning. What the phrase indicates is that inputs come at us as a sequence of events and ideas. This is obvious when you consider reading a book or listening to a lecture, but it also applies to the events of daily life. One thing follows another.

An important insight related to learning is that what is stored when imagined by cognitive psychologists and to some extent supported by neuroscientists is best understood as a network with links among nodes differing in strength. It follows that some sort of processing and organization is necessary to get from the form of the input to the form of the storage.

When I first encountered this notion of changing information formats, I was reminded of something I used to present to my educational psychology classes. There appear to be different types of memory stores. What might be described as knowledge is stored as a web of concepts connected by links — semantic memory. We also store inputs using other formats, with the most relevant one for this description being episodic memories. I liked to describe episodic memories as stories as this was a convenient way to explain an approximation of this concept. We like stories, and the value of stories can be noted in the way we interact with others. Often, one person tells a story, and then the other individuals respond with a story of their own both to indicate they understand and to further the interaction. We often include stories in writing and teaching as a way to provide examples of ideas. Episodes are stored with our cognitive web linked with the abstract nodes of semantic memory.

Episodic memories (stories) have a time course or sequence. What I speculated about for my class was that stories are often processed into semantic memory and one of the issues with learning from experiences including class lectures was whether the lecture as story was processed into semantic memory. I asked about how students studied their notes and whether they repeatedly went through them and could even imagine where specific items, perhaps a graph, appeared in a location within their notebook. I suggested that this capability indicated at least some aspects of an episodic representation was being retained. The content stored in that fashion may not have been processed for understanding.

When are academic episodic representations converted? I suggested for some this may happen at the time of an exam. A question might refer to an example from class and ask for an application. If the class example had not been processed during the lecture or during study as related to a concept or principle, the student would have to go through this process of abstraction and organization in trying to answer the question.

External activities to encourage processing

I often write about generative activities — external tasks that change the probability of desirable cognitive behaviors involved in understanding and learning. The idea here is that we can understand and learn by self-imposed and self-guided thinking, but this may not happen for a variety of reasons. External tasks can be provided to increase probabilities. Questions are an easy example. Questions encourage different types of processing depending on the type of question. Some encourage recall, and others encourage application.

Some generative activities might have value in converting a linear input. Creating an outline requires a hierarchical organization of ideas. Something closer to the desired output as a web would be mind mapping or concept mapping. If you are unfamiliar, I would recommend Davies ( 2011) as a resource that would explain more than you probably want to know about mind mapping, concept mapping, and argument mapping. Among other things, I learned from this source was that there are differences among these tactics and many subtleties or variants of each. Some researchers and educators who apply concept maps go deep into fine details.

One differentiation among those who conduct concept mapping research (the general term I have always preferred) is whether maps are constructed by learners or constructed and provided by teachers/authors. Concept mapping assignments would be a type of generative activity and encourage the translation of a linear input into a representational web. The provision of a mind map in support of a linear narrative is different and is an attempt to show the structure that the presenter imagines as a way to encourage the learner to consider relationships among ideas that might expand whatever organization of ideas the learner had already established.

Smart notes and the creation of web structures

I am making a transition here that the uninitiated may have trouble following. Some of these who have made the study of note taking a serious focus have developed approaches that are quite different from the continuous paraphrasing and summarization that most learners use in recording notes in a notebook or on a laptop. I think of a smart note (a formal term as used here) as a concise note focused on a specific idea with enough context that it will still convey the original meaning at a future date to the note taker or others with a reasonable background. Think of a smart note as a building block that can then be combined with other smart notes in a cumulative way. The idea of specificity is that a given block can be combined with other such representations in a variety of ways. You can build different structures from different combinations of ideas. Notes are connected in several ways. Some of the possible connections can be attached as metadata — tags and links among notes.

Hopefully, the similarity between such notes and links and concept maps might now become apparent.

A web of notes within Obsidian

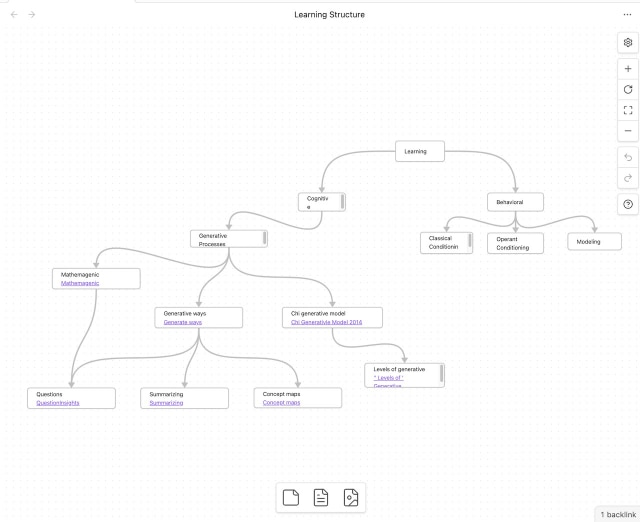

Obsidian is my personal note-taking tool, and it fits well with the idea of isolating specific ideas or concepts and then identifying connections between these specific notes over time. Rather than focus on using this tool as a learner, which has been the focus of multiple posts in the past, my intent here is more on the potential of sharing the structure of personal notes with others. So, in keeping with the theme of converting linear narrative chains, how might an instructor or author share the structure behind what they might present as a lecture or written product?

I briefly mentioned how a colleague who teaches history shares his background content with students in a previous post. Here, I want to describe the use of a mapping tool, Canvas, available as an extension to Obsidian. Obsidian includes its own tool for creating a map of notes and connections, but Canvas is more typical of what I have already described as a tool for concept mapping.

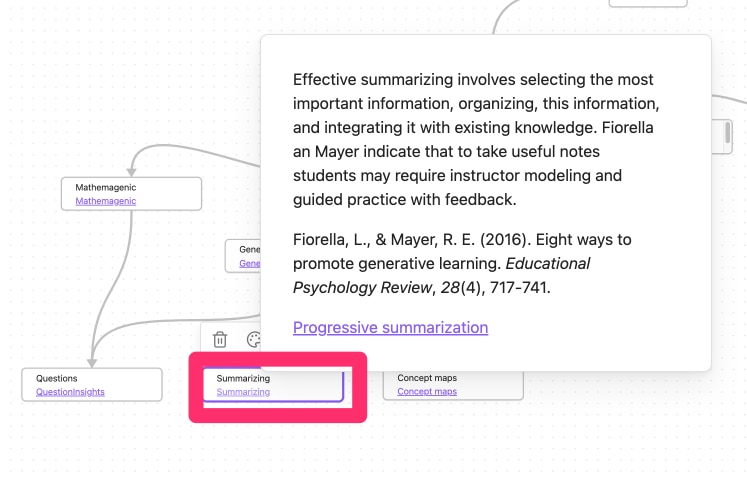

The following image shows a Canvas concept map I quickly created to show I might share the web of ideas that might be the basis for a couple of presentations I might offer describing the behavioral and cognitive models of learning. I had to find a workaround for the way Canvas was designed to work. The intention is that a Canvas web would show the entirety of notes. So, if you imagine a note consisting of a paragraph of content, you might have Canvas nodes representing concepts (as is the case in my example) linked with visible nodes containing entire paragraphs. This works fine if you are in control of a device as you can shrink and expand the content that appears on the screen very easily and expand a portion of the display if you need to make the paragraph larger so you can read it. I used a different approach, repurposing a typical text note as a node descriptor and then a link. The link would reveal the linked note layered on the basic map (second image).

To make this work in practice, you would have to pay for an Obsidian service ($8 a month) called Publish. Obsidian is a device-based tool, but Publish offers a web-based interface and storage option that allows others to view your Obsidian vault (a collection of notes).

There are likely multiple ways in which an individual could generate a shareable web experience for students. I have been focused on how I might do such a thing based on the note tool (Obsidian) I use. As another example example, in a previous post, I explored how Padlet could be used by a middle school or high school teacher to share a web of concepts and notes.

Summary

Students experience information as linear narrative chains even though the information within is likely based on a web of concepts and ideas. Since human memory is more web-like, the learner must transform a sequence of ideas to fit within his or her personal webs. Concept maps have been used to encourage the building of a personal web and can also be used for the author/teacher to share his/her web to assist in the construction of a personal representation. Note-taking tools based on the identification and linking of core ideas (Smart Notes) offer a related experience on the part of learners and possibly with some adaptations provide a way to share the structure the author/teacher used to generate their presentations.

Resources:

Ahrens, S. (2022). How to take smart notes: One simple technique to boost writing, learning and thinking.

Davies, M. (2011). Concept mapping, mind mapping and argument mapping: what are the differences and do they matter? Higher education, 62, 279-301.

Hay, D., Kinchin, I., & Lygo-Baker, S. (2008). Making learning visible: The role of concept mapping in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 33(3), 295–311.

29 total views , 2 views today