In reading and then writing about Willingham’s The Reading Mind, the author makes some interesting arguments about the relationships between what we know and reading comprehension and between the time spent reading and what we know. As the reciprocal relationship implies, this is a cognitive explanation of how the rich get richer. The author throws in a related analysis of whether our commitment to spending time with technology has diminished the likelihood that we are now benefiting from this relationship. What follows is my embellished summary with a few updates.

I like to think of Willingham’s description of reading as explaining how the inputs to comprehension come simultaneously from opposite directions. The bottom-up inputs come from the page – letter/phoneme recognition, word recognition, word meaning, broader understanding. The top-down inputs come from stored information (memory) – general knowledge, specific knowledge, broad understanding of the passage being read, sentence meaning, etc. You probably recognize that these inputs are really the same series just listed in opposite directions. It turns out these inputs help each other out as many are being processed at the same time. Some of these interactions you may not recognize and may surprise you. For example, a letter at the beginning of a word can be identified faster than the letter in isolation. Others, you may recognize if I bring them to your attention. For example, the understanding of a sentence may help you assign meaning to an unfamiliar word in that sentence. The battle over what is commonly described as the “science of reading” is focused on the early bottom-up processes. Should early reading experiences emphasize associating sounds with word components or should word recognition and context receive greater attention? It might be helpful to understand why the science of reading may seem to change over time because effective reading depends on multiple processes acting to support each other. Many subskills end up being important. I am more interested here in the top-down processes. Once we get past learning the basics of reading, how does reading both depend on and develop what we know?

Willingham proposes that it is never possible for a writer to explain a topic in complete detail and an author must rely on what readers already know to fill in some elements from existing knowledge. So when a reader is exposed to new material understanding is dependent both on reading skill and existing knowledge. What we already know has a surprisingly large impact on what we comprehend and retain. This claim can be demonstrated on two levels – general knowledge and topic specific knowledge.

Anne Cunningham and Keith Stanovich conducted an interesting study of high school students in which they had the students take a test of general knowledge. General knowledge involves all kinds of random information. In their research, students were asked about factual knowledge of science, history, and literature and the accomplishments of people from history, science, sports, and music. It was not that the knowledge of the specific topics was necessarily important, but rather that the scores obtained were predictive of the level of general knowledge more broadly. The researchers also administered a standard test used to evaluate reading comprehension skills. These two variables – general knowledge and comprehension skill were strongly correlated. More capable readers probably have learned more from reading, but what they have learned may also be a factor in determining their reading skill. Such differences are partly responsible for the advantage some students gain from general life experiences that cannot be provided while in the classroom.

The advantage of what we know to reading performance is made clear in studies that investigate the importance of specific knowledge in understanding content related to that knowledge. Willingham used a study based on reader differences in understanding the game of soccer. This surprised me as I was aware of a very similar study based on the game of baseball. A general description of the clever methodologies of these studies will explain how reading skills and relevant knowledge were differentiated. These studies (Recht & Leslie, 1988; Schneider, Korkel & Weinert, 1989) were conducted with younger learners. Depending on the study, these learners were given a test to evaluate their knowledge of baseball or soccer. Scores on reading comprehension tests were also available. These two measures were used to identify four groups of learners – high on both measures, high on one measure and low on the other, low on both measures. After reading a story about part of a baseball game or a soccer match, readers were asked to recall as much as they could from the story. The grouping of readers allowed a way to statistically isolate the impact of reading ability from background knowledge on what was retained. Relevant knowledge was at least as important as reading proficiency to what was taken away from the reading experience. By the way, this type of research should be relevant to those who argue access to Google is equivalent to knowing things. What you can find through search does not offer the same benefit to immediate processing as what you already know.

Leisure Reading and Technology

Leisure reading plays a unique role to developing readers because the time devoted to leisure reading varies far more than the time spent reading in schools. As adults, if we read many of us only engage in reading that would fall in this category. If engaged in an educational setting, leisure reading augments assigned reading as a reading skill development opportunity and as an opportunity to expand the acquisition of general knowledge and that is important in improving the effectiveness of reading.

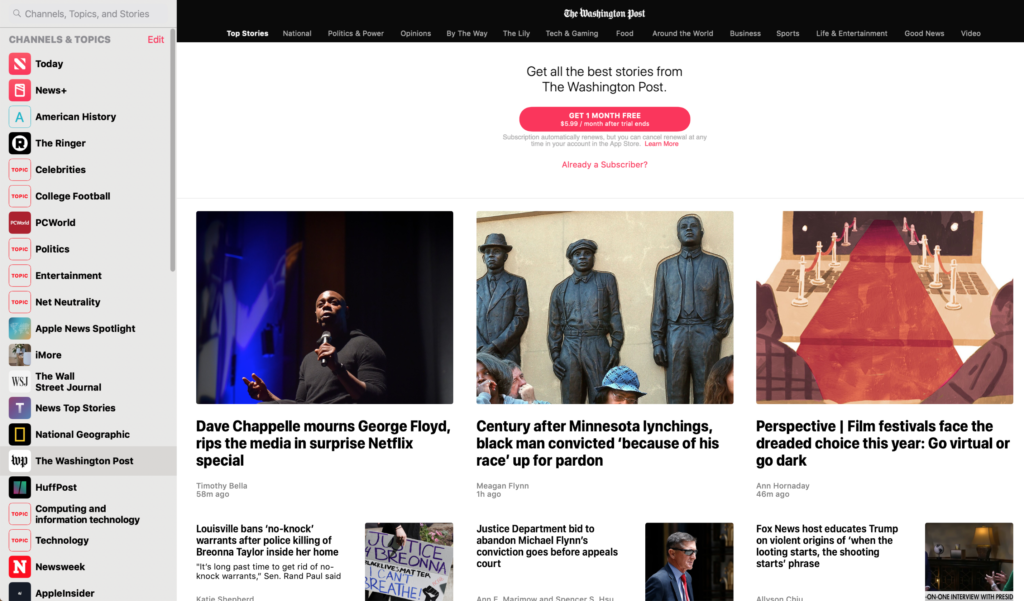

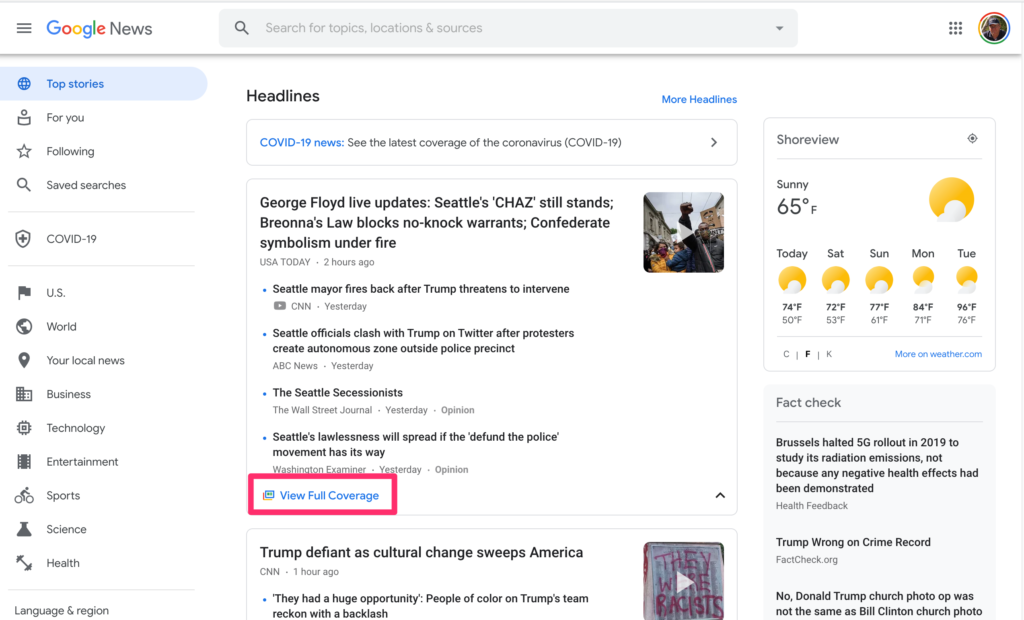

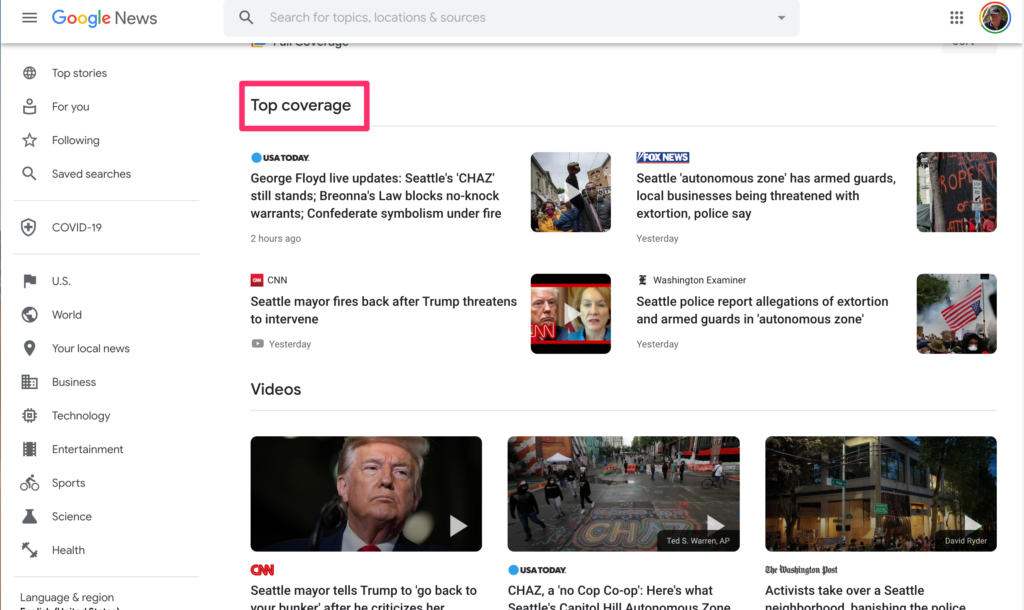

In the discussion of technology and reading, Willingham considers both whether reading from a screen offers the same benefits as reading from paper and whether our constant use of technology has displaced time spent reading. Willingham acknowledges the research that demonstrates a small benefit for reading from paper. Like my posts on this topic, he sees this difference to be of little consequence acknowledging that the root cause is unknown. My embrace of screen reading is related to the long-term advantages of the production of digital notes and searchable highlights that can be organized and efficiently searched.

The notion that screen time comes at the cost of reading time (displacement) was countered with what to me were some surprising data. In his focus on leisure reading, Willingham argues that Americans never did read much and that this amount of time has not diminished from pre-internet days. I checked Willingham’s sources on this topic and found a more recent survey of adolescent reading behavior (Rideout and colleagues 2022). Reading time has actually increased a bit, but the average daily reading time has now reached 34 minutes. Twenty-four minutes involve books (paper or ebooks) and the rest newspapers, blogs, and other long-form content. I don’t find this average that disturbing given students are also reading for their classes and may have homework. The more disturbing version of this basic statistic is the variability. Nearly 20% of adolescents indicate they read nothing beyond what is assigned at school. Recent data on adult behavior indicates that the average daily reading time is about 15 minutes. Adults don’t set a very good example.

Summary

Reading both is an important source for what we know and what we know benefits the level of reading proficiency we achieve. Reading is an activity we control as individuals and if we so choose we can benefit from spending leisure time in this way.

References:

Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental psychology, 33(6), 934.

Recht, D. R., & Leslie, L. (1988). Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers’ memory of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.80.1.16 (baseball)

Rideout, V., Peebles, A., Mann, S., & Robb, M. B. (2022). Common Sense Census: Media use by tweens and teens, 2021. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media

Schneider, W., Korkel, J., & Weinert, F. E. (1989). Domain?specific knowledge and memory performance: A comparison of high? and low? aptitude Children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81( 3), 306–312. (Soccer)

Willingham, D. T. (2017). The reading mind: A cognitive approach to understanding how the mind reads. John Wiley & Sons.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.