I am trying something different with one of my longer writing projects.. My wife and I had a 15 year run with a commercial textbook for the “technology for teachers” undergraduate teacher preparation course. Fifteen years translates as 5 editions of the book. This course does not generate the review of a large lecture course (e.g., Introduction to Psychology), but there is less competition in the area of our book and we did well financially.

As we gained a lot of experience allowing us to analyze the textbook industry and the niche in which we published, we became very aware of the backlash against textbook costs (ours sold for $140 to students) and began to identify issues a traditional textbook for this niche could not address.

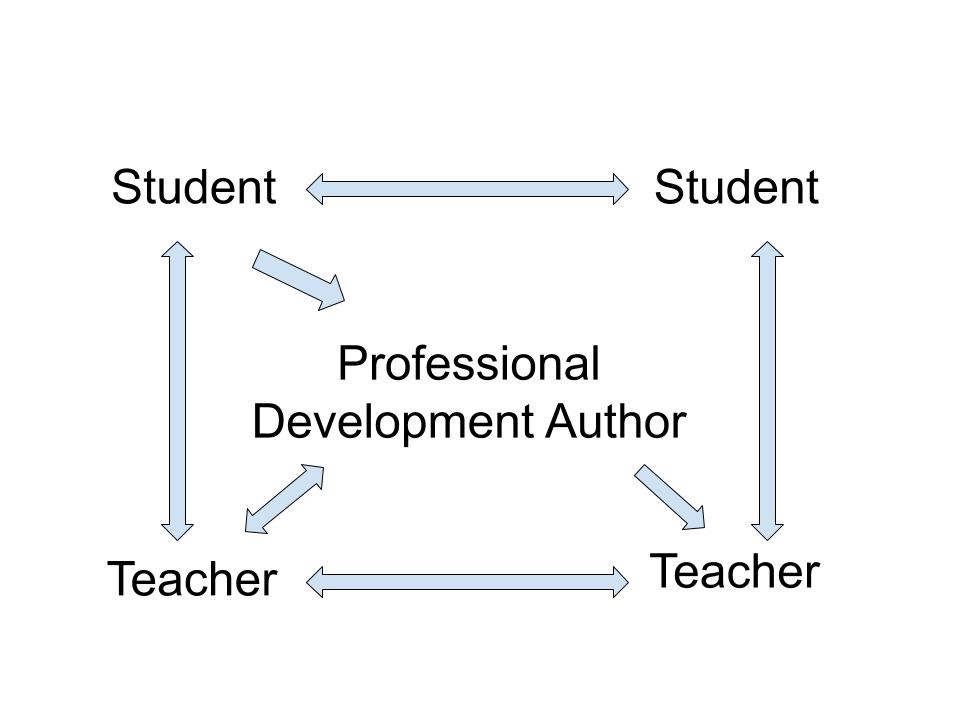

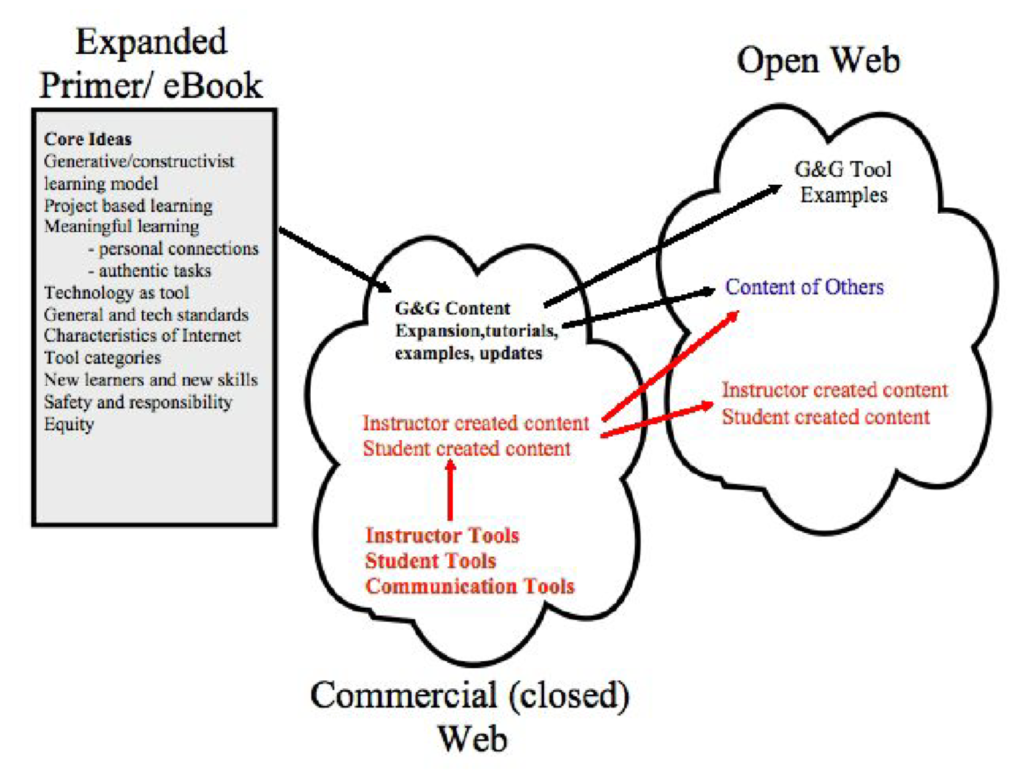

We came up with a plan to publish a much shorter version we called a Primer and wanted to match this with online resources. We proposed a $29 Primer and intended to serve the online content ourselves. I still think some of our arguments for this approach make sense. For example, those intending to teach high school and early elementary have very different interests in what to do with technology. Why not provide the basics in a Primer and then a larger variety of content for specific content areas and grade levels online? Technology is a field that moves quickly and keeping content current is a tremendous challenge. Not only did we publish once every three years, but 9-12 months were set aside to generate the next edition. You see the time lag that is created. Why not write online continually to keep a given textbook current?

Textbook companies think differently about their relationship with the authors they hire. A proposal such as paying someone to write continuously does not make sense to them even though they might appreciate the issue of keeping content current. They typically have a couple of books in a niche and their field reps encourage the adoption of the most recent book in a niche. This is more because of the used book market than the issue of currency and the issue of a general approach rather than what would be best for a given book is the perspective they take. At the time (this has changed since), combining online content with a physical product was also a foreign idea that did not translate as easily into income.

Anyway, we agreed to go our separate ways and were given our copyright back so we could pursue our interests with another company or with an outlet such as Kindle.

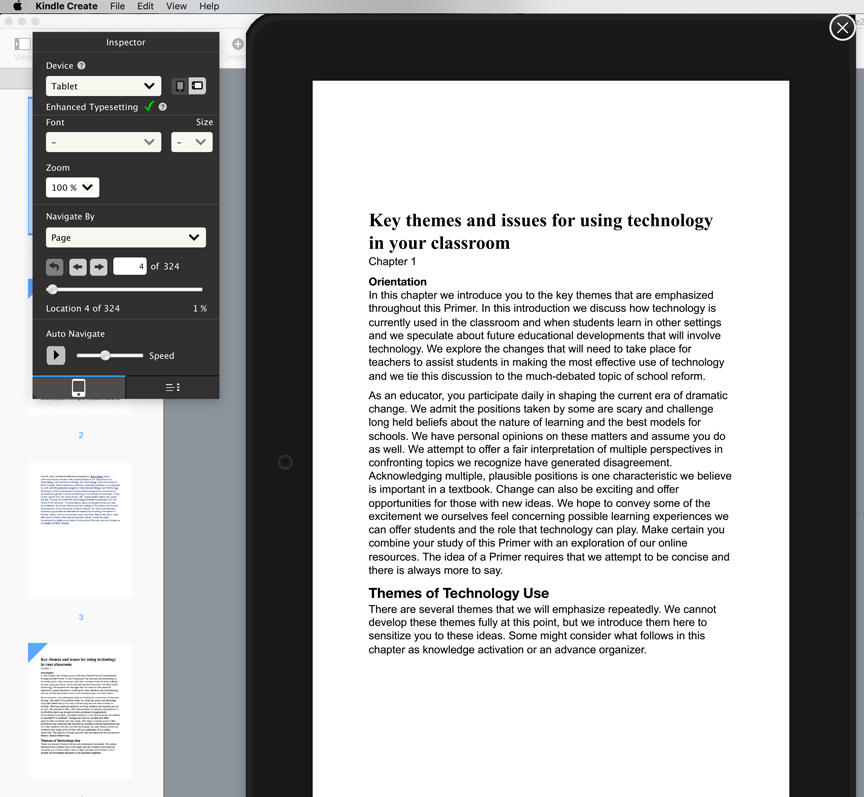

We continue to offer a version of this textbook through Amazon. I developed a second resource (Layering for learning) which was not really a full-length textbook, but concentrated on specific online services I proposed educators could use to make more effective use of web pages and online videos. It is this second “book” that I have decided to take in a different direction.

My professional writing activities have long been mostly a hobby. We made our money on our original textbook, but now my work is mostly about exploring topics in online publishing. Instead of $140, the online textbook sells for $9. Same basic book. I think it appropriate content that takes considerable time to create be treated as having value and I have always require some payment for my professional work even if mostly symbolic. So, what other outlet and approach can I explore as an alternative to Amazon?

Here is my new project. I am updating my layering book and serializing it on Medium. If you have not used Medium directly, you may have encountered work offered on Medium through a search engine. Sometimes you could read what the search engine found and sometimes you may have found that the content was behind a paywall. There are two competitors in this space – Substack and Medium. With Substack, if an author wants to be compensated for her work, she requires readers to subscribe to her work for a price. A reader makes a specific commitment (usually $5 a month or so) to specific authors. With Medium, you pay a subscription fee ($50 a year) and then read whatever you want from as many authors as you want. Medium takes a cut and then allocates the rest to the authors based on several variables they use to define value. Like other social outlets for the vast majority of writers, you receive little money (I hope to make enough to cover my own Medium subscription fee). I think of it as a way to keep score. Do people find what I write interesting and of value? What are the options for those who generate the kind of content I create and how do different options compare?

If you are not a Medium users, I think you are allowed three free reads a month and the Introduction to my serialized book is explained in greater detail.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.