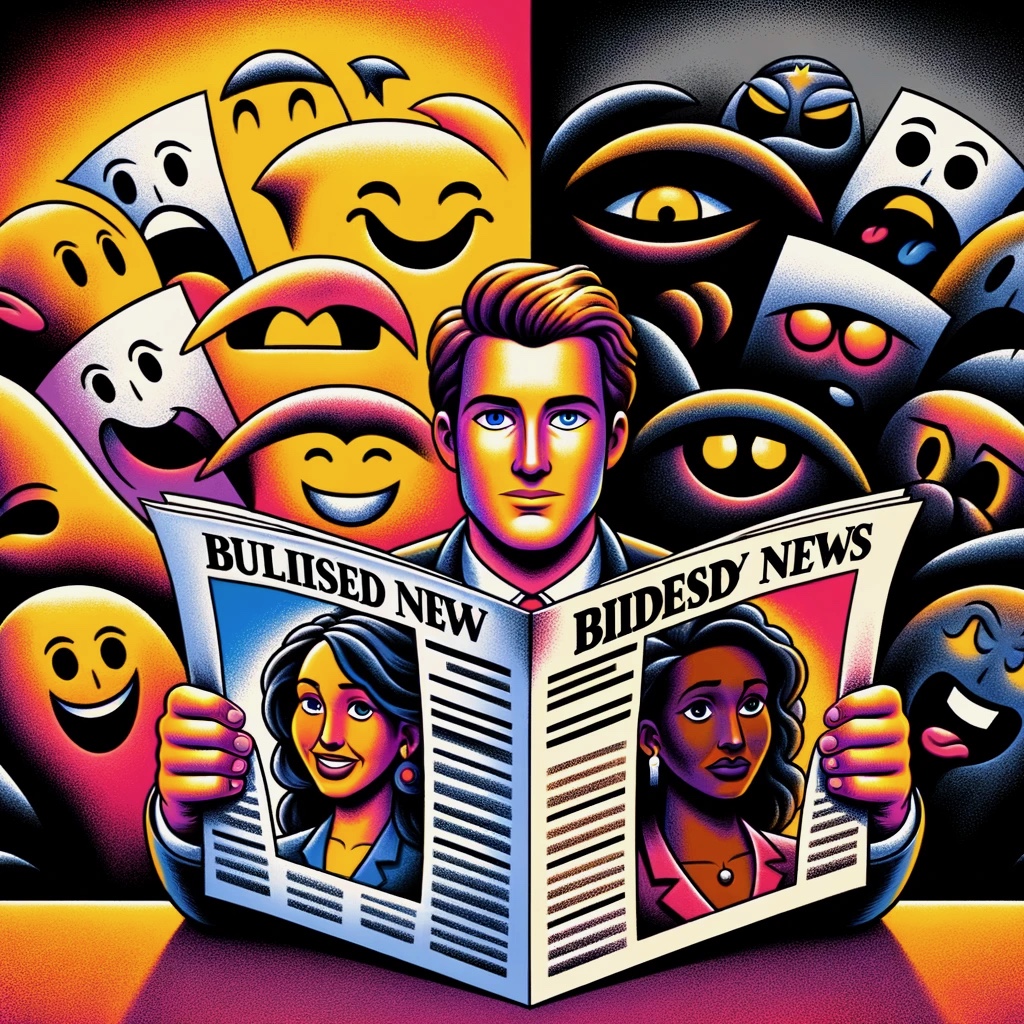

In so many areas, the potential of the Internet seems subverted by the design decisions made by those who have built businesses on top of what seemed an innovation with so much potential. My focus here is on the political division and animosity that now exists. Since the origin of cable television, we have had a similar issue with an amazing increase in the amount of content, but the division of individuals into tribes that follow different “news” channels that offer predictably slanted accounts of the news of the day to the extent that loyal viewers are often completely unaware of important stories or different interpretations of the events they do encounter.

The Internet might have seemed a remedy. Social media services are already functioning as an alternative with many now relying on social media for a high proportion of the news individuals encounter. Unfortunately, social media services are designed in ways that make them as biased and perhaps more radicalizing than cable tv news channels.

Social Media and Internet News Sources

Here is the root of the problem. Both social media platforms and news sources can use your personal history to manipulate what you read. Social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, X, Instagram) use algorithms that analyze your past behavior, such as the posts you’ve liked, shared, or commented on, as well as the time you spend on certain types of content. They use this information to curate and prioritize content in your feed, including news articles, which they predict will keep you engaged on their platform. You add the way algorithms work on top of the reality that those we follow as “friends” are likely to have similar values and beliefs and what you read is unlikely to challenge personal biases you hold. To reverse the Rolling Stone lyric, you always get what you want and not what you need.

News sources are different from social media in which you identify friends and sources. However, news sources can also tailor their content based on the data they gather from your interactions with their posts or websites. These practices are part of a broader strategy known as targeted or personalized content delivery, which is designed to increase user engagement and, for many platforms, advertising revenue.

Many major news organizations and digital platforms target stories based on user data to personalize the news experience. Here are some examples:

Google News: Google News uses algorithms to personalize news feeds based on the user’s search history, location, and past interactions with Google products. It curates stories that it thinks will be most relevant to you.

Apple News: By using artificial intelligence, Apple News+ offers a personalized user experience. Publishers can adapt content based on readers’ preferences and behavior, leading to stronger engagement and longer reading times.

The New York Times: The New York Times has a recommendation engine that suggests articles based on the user’s reading habits on their website. If you read a lot of technology-related articles, for example, the site will start to show you more content related to technology.

Are Federated Social Media different?

Federated social media refers to a network of independently operated servers (instances) that communicate with each other, allowing users from different instances to interact. The most notable example of a federated social media platform is Mastodon, which operates on the ActivityPub protocol. On Mastodon, you can follow accounts from various instances, including those that post news updates. For example, if a news organization has an account on a Mastodon instance, you can follow that account from your instance, and updates from that news source will appear in your feed. This system allows for a wide range of interactions across different communities and servers, making it possible to follow and receive updates from diverse news sources globally.

Your Mastodon timeline is just a reverse chronological feed of the people you follow, or the posts from people on your instance only (and not across all of Mastodon). There’s no mysterious algorithm optimized for your attention. So, with Mastodon, a news source you follow may have a general bias, but you would get the stories they share without prioritization by an algorithm based on your personal history.. This should generate a broader perspective.

With Mastodon, you can join multiple instances some of which may have a focus. For example, I first joined Maston.Social which at the time was that instance most users were joining. I have since joined a couple of other instances (twit.social & mastadon.education) that have a theme (technology and education), but participants post on all kinds of topics. An interesting characteristic of federated services is that you can follow individuals from other instances – e.g., you can follow me by adding @grabe@twit.social from other instances.

This brings me to a way to generate a news feed the posts from which will not be ordered based on a record of your personal use of that instance. Many news organizations have content shared through Mastodon and you can follow this content no matter the Mastodon instance you join. Some examples follow, but you can search for others through any Mastodon account. You follow these sources in the same way you would follow an individual on another account.

@npr@mstdn.social

@newyorktimes@press.coop

@cnn@press.coop

@wsj@press.coop

@bbc@mastodon.bot

@Reuters@press.coop

Full access may depend on subscriptions. For example, I have a subscription for the NYT.

So, if a more balanced feed of news stories appeals to you. Try joining a Mastodon instance and then follow a couple of these news sources.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.