Thinking is not visible to self and others and this reality limits both personal analysis and assistance from others. I have always associated the request to show your work associated with learning math so subprocesses of mathematical solutions can be examined, but the advantage can be applied when possible to other processes. I have a personal interest in the ways in which technology can be used to externalize thinking processes and the ways in which technology offers unique opportunities when compared with other methods of externalization such as paper and pen.

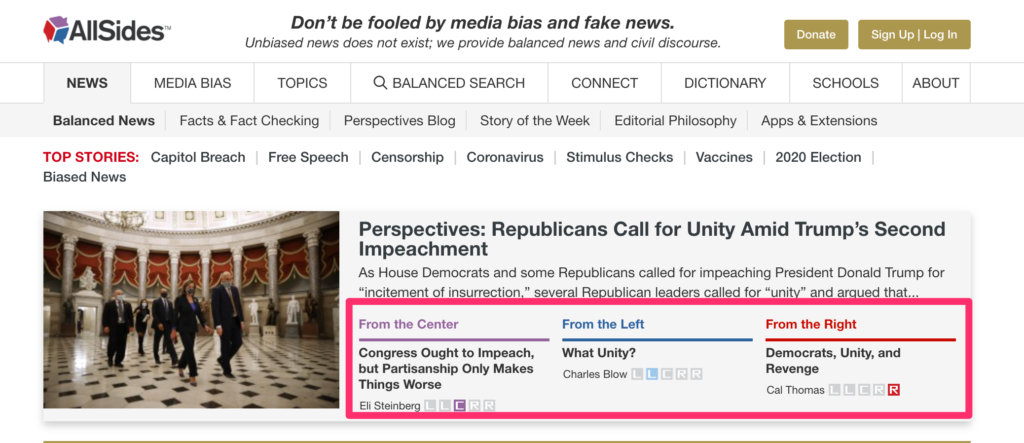

Ideas from different areas of interest sometimes come together in unexpected ways. This has been a recent experience for me with a long-term interest in argumentation and digital tools applied to learning. Argumentation may not spark an immediate understanding for educators. It sometimes help if I connect it with the activity of debate, but it relates to many other topics such as critical thinking and the processes of science as well. It relates directly to issues such as the distribution of misinformation online and what might be done to protect us all from this type of influence.

For a time, I was fascinated by the research of Deanna Kuhn and wrote several posts about her findings and educational applications. Kuhn studied what I would describe as the development of argumentation skills and what educational interventions might be applied to change the limitations she observed. It is easy to see many of the limitations of online social behavior in the immaturity of middle school students engaged in a structured argument (debate). Immature interactions involving a topic with multiple sides might be described as egocentric. Even though there is an interaction with a common topic, participants mostly state the positions they take with and frequently without supporting evidence. As they go back and forth, the seldom identify the positions taken by an “opponent” or offer evidence to weaken such positions. Too often, personal attacks follow in the “adult” online version, and little actual examination of supposed issues of interest is involved.

Consideration of the process of clearly stating positions and evidence for and against maps easily to what we mean by critical thinking and the processes of science. In the political sphere what Kuhn and similar researchers investigate relates directly to whether or not policy matters are the focus of differences of opinion.

Externalization and learning to argue effectively

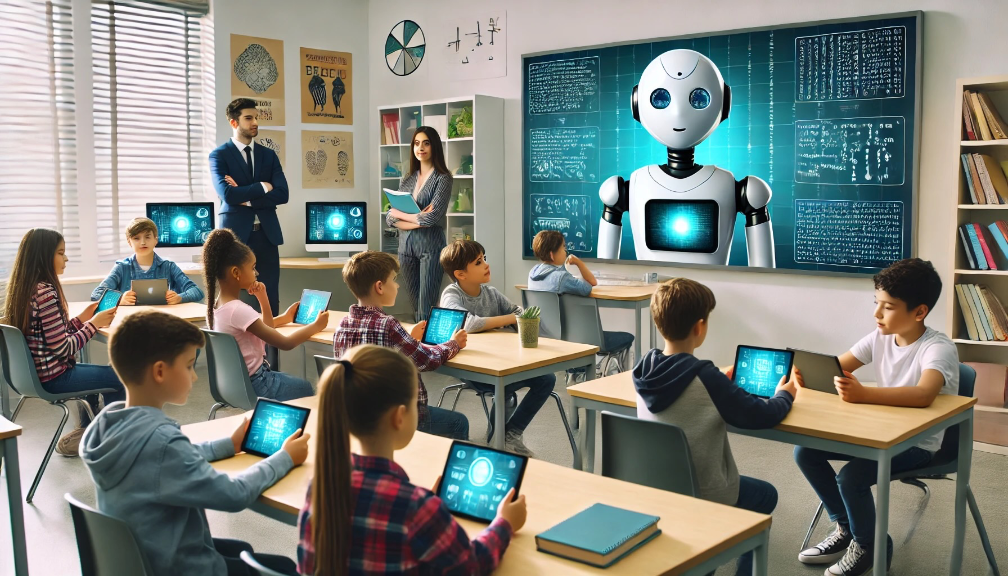

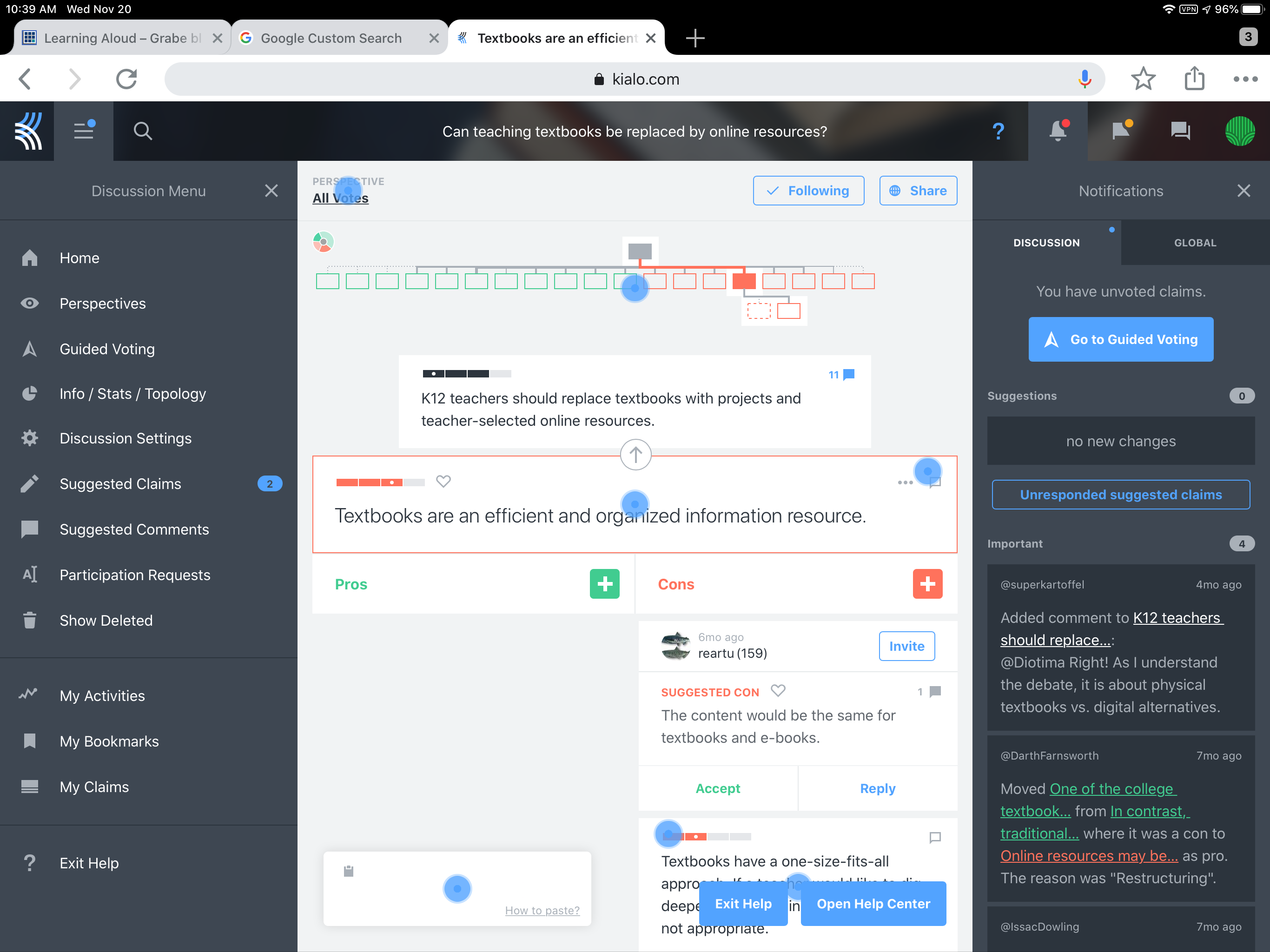

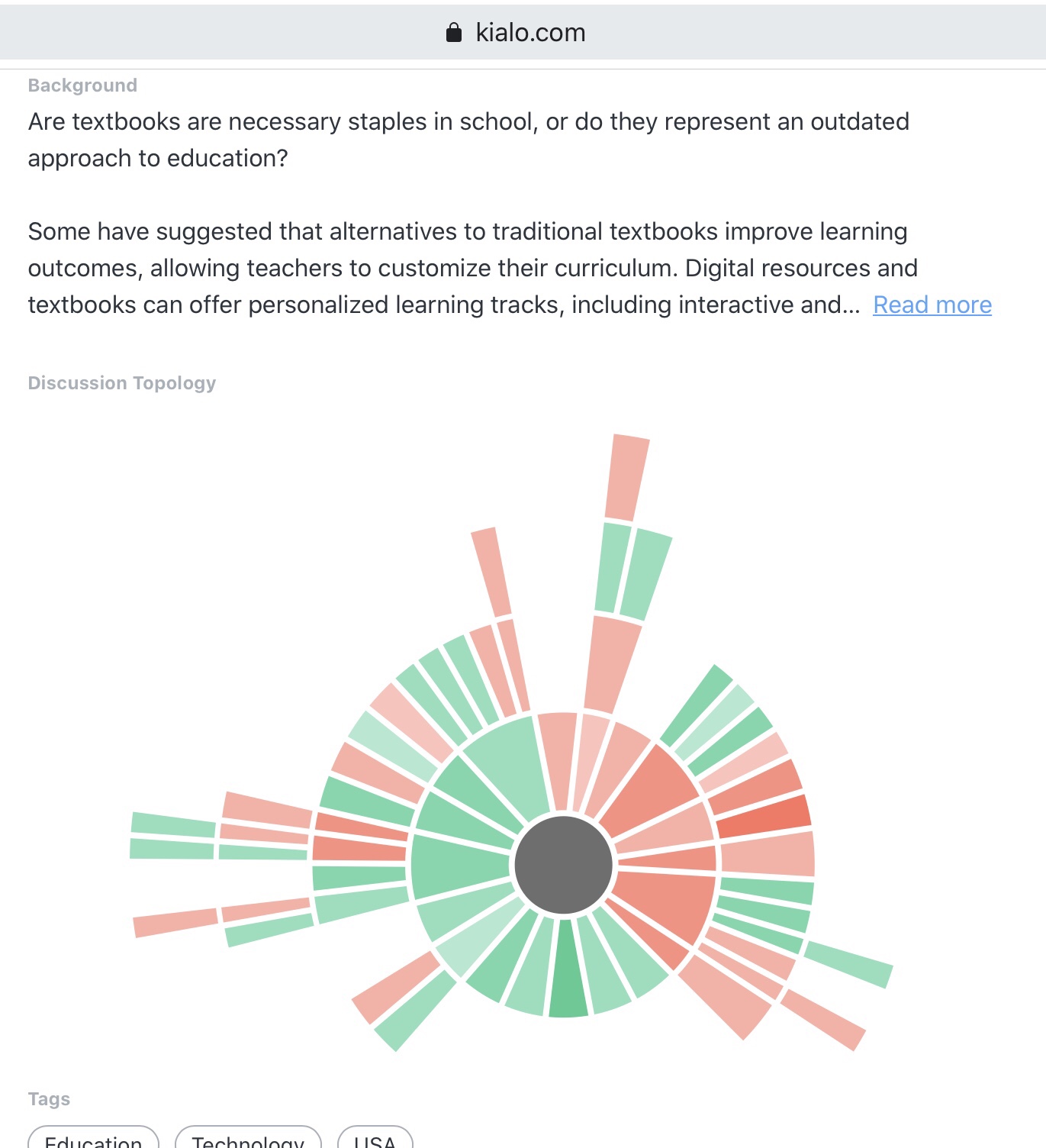

Kuhn proposed that to improve (develop) critical thinking skills learners would benefit from experiences encouraging reflection. An approach that proved productive was based in multiple studies on two techniques for encouraging reflection. Across multiple age groups (middle school, high school, college students) she had pairs of participants argue using online chat. A pair had to agree on a given “move” or statement before submission (externalizing rationales for consideration) and submitting statements in chat both allowed an opportunity to focus on the message with interference from the face-to-face issues that are present in formal debate and to create a record that could be critiqued. In some studies, the participants were asked to complete forms asking for a statement of the positions taken by opponents and evidence offered in support of these positions. The effectiveness of the treatments was examined following training without such scaffolds.

AI arguments result in an external record

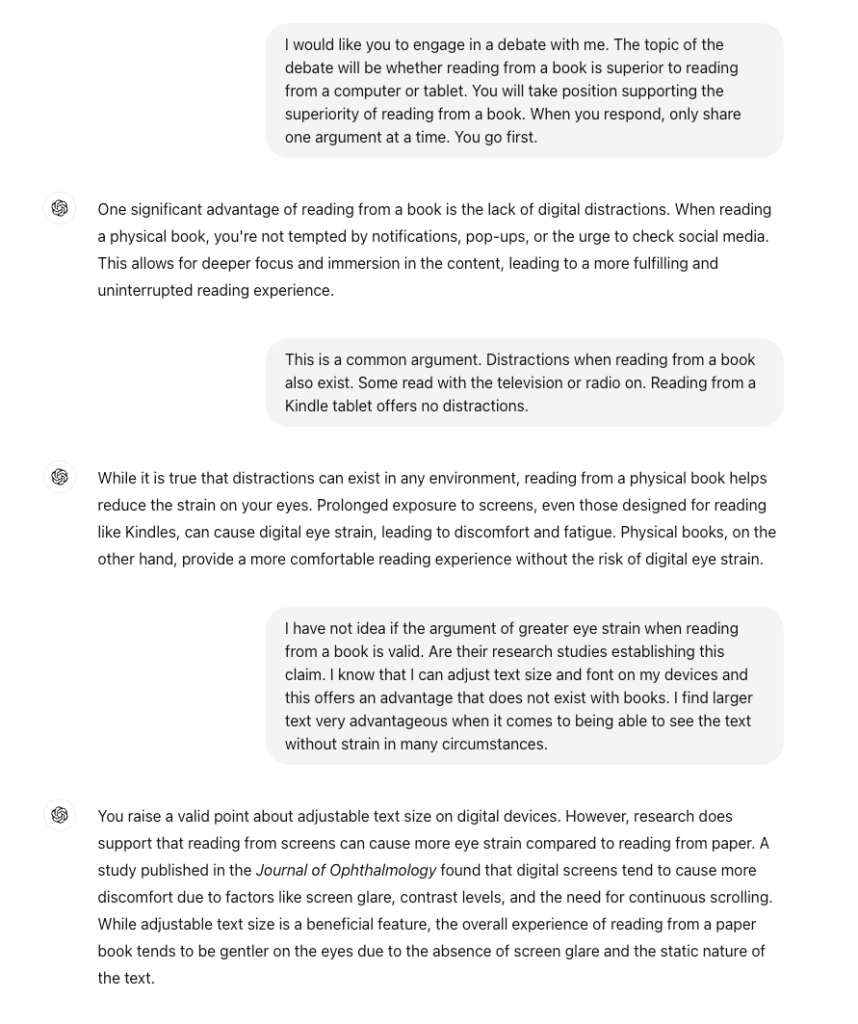

I and others have been exploring the experience of arguing with an AI opponent. One insight I had while exploring this activity was that it resulted in an external product that could be examined much in the way Kuhn’s chat transcripts could be examined. Classroom applications seem straightforward. For example, the educator could provide the same prompt to all of the students in the class and ask the students to submit the resulting transcript after an allotted amount of time. Students could be asked to comment on their experiences and selected “arguments” could be displayed for consideration of the group. A more direct approach would use Kuhn’s pairs approach asking that the pairs decide on a chat entry before it was submitted. The interesting thing about AI large language models is that the experience across submissions of the same prompt are different for each individual or for the same individual submitting the prompt a second time.

I have described what an AI argument (debate) looks like and provided an example of a prompt that would initiate the argument and offer evaluation in a previous post. I have included the example I used in that post below. In this example, I am debating the AI service regarding the effectiveness of reading from paper or screen as I thought readers are likely familiar with this controversy.

…

Summary

Critical thinking, the process of science, and effective discussion of controversial topics depends on the skills of argumentation. Without development, the skills of argumentation are self-focused lacking the careful identification and evaluation of opposing ideas. These limitations can be addressed through instructional strategies encouraging reflection and the physical transcript resulting from an argument with an AI-based opponent provides the opportunity for reflection.

References:

Iordanou, K. (2013). Developing Face-to-Face Argumentation Skills: Does Arguing on the Computer Help. Journal of Cognition & Development, 14(2), 292–320.

Kuhn, D., Goh, W., Iordanou, K., & Shaenfield, D. (2008). Arguing on the Computer: A Microgenetic Study of Developing Argument Skills in a Computer-Supported Environment. Child Development, 79(5), 1310-1328

Mayweg-Paus, E., Macagno, F., & Kuhn, D. (2016). Developing Argumentation Strategies in Electronic Dialogs: Is Modeling Effective. Discourse Processes, 53(4), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2015.1040323

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.