I recently listened to Kara Swisher interviewing Jonathan Haidt the author of The Anxious Generation. I checked on this book and it is #1 on the New York Times nonfiction list this week. I provide a comment on the ranking because the ranking would indicate the book was receiving a great deal of attention from the general public and the message must have substantial appeal.

Briefly stated, the book argues that rising anxiety and mental health issues of adolescents are significantly determined by overparenting and the amount of time spent, especially by adolescent females, on social media. I have personal comments related to this issue particularly Haidt’s recommendation for phone use in schools, but I would encourage you to listen to the interview because Swisher pushes back and the interchange offers some useful insights into whether cellphone activity is responsible for an increase in mental health problems.

Certain facts are well established: a) adolescents spend a great amount of time on their cellphones since the introduction and wide purchase of iPhones (this specific event figures heavily in some arguments), and b) beginning before the Covid shutdown and continuing to the present adolescents, particularly females, have shown an increase in mental health issues. The big question, the focus of Haidt’s book, and lots of research (citations will be included) is whether there is a causal relationship such that a significant proportion of the increase in mental health problems can be accounted for by the great amount of online activity mostly using personal phones.

The amount of time adolescents and many of the rest of us spend online is staggering. PEW has done regular surveys of teens to quantify their online activity and provides the following data points.

- YouTube (95%), TikTok (67%), Instagram (61%), and Snapchat (60%) are among the most popular social media platforms used by teens.

- On average, teens spend 1.9 hours daily on YouTube and 1.5 hours on TikTok, with males spending more time on YouTube and females on TikTok.

- Around 35% of teens say they use at least one of the top social media platforms “almost constantly”.

As an aside, one of the “quality studies” Haidt mentioned to support his claim in the Swisher interview involved adult use of Facebook (Allcott et al. 2022). Swisher asked for examples of manipulative research showing that phone use and depression were related and Haidt provided this study. PEW doesn’t have much to say about Facebook activity among adolescents because the level has dropped so low. Haidt acknowledges that few quality studies exist with adolescents because doing manipulative research before the age of 18 is very difficult. This is why so many researchers use college students – they are available and they can participate.

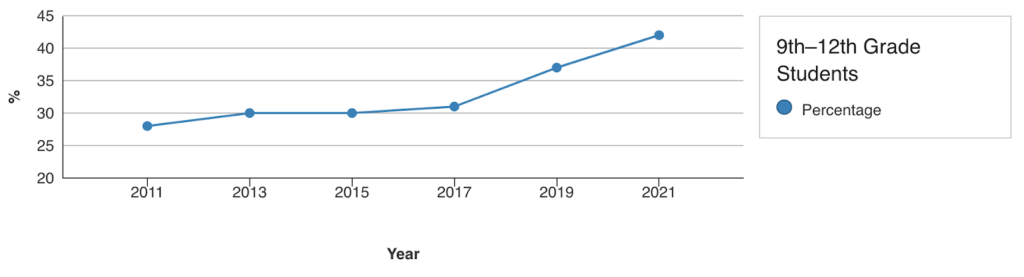

Adolescent mental health issues have increased year by year with a big jump during the COVID years. Data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention tracking depression provide a good example of this trend. The following chart was taken from this report.

So, facts demonstrating adolescents’ heavy use of phones and increasing mental health issues are solid. Now, are these two variables related and how? All I can say is that the research or perhaps more accurately the interpretation of the research is messy. I understand that parents, educators, and policymakers just want the researchers to provide a clear summary, but this just isn’t happening.

You have books such as Haidt’s (I would also recommend Jean Twenge) and medical experts (this summary of research from the National Library of Medicine) offering analyses of the research that come across placing a heavy burden of blame on cell phone use. I can also recommend scholarly meta-analyses of the phone-mental health students to reach just the opposite decision (e.g., Ferguson, et al. 2022). I admit summaries of many of the same research publications that come to very different conclusions are challenging. I read and comment about this type of controversy in other areas (should notes by taken on paper or laptop, are books better understood on paper or from the screen) in which I have read most of the relevant studies and can offer a personal opinion. I am not a clinical psychologist and in this case, I do not want to go on the record telling parents or teachers what they should do about kids and cell phones. If you are interested, I hope I have offered some of the resources you can use to get started.

What I do want to talk about

Getting back to Haidt’s book. Haidt makes several specific recommendations based on his conclusion that cellphone use is damaging.

- Schools should be phone free zones

- Children should first be provided a phone specialized for communication and not Internet use (e.g., a flip phone)

- Adolescents should not have access to a smartphone until high school (but see #1)

- Access to social media should be changed from 13 to 16.

Some additional Haidt comments on schools as phone free zones are:

- The agreement of schools to ban smartphones is important because a total ban applies to all students and avoids the problem of some students having access and some students not.

- School policies such as having access only during class or having phones in backpacks or lockers don’t work.

I do not support classroom bans on smartphones. In part my logic is based in research experience I do have and this work involved cyberbullying. A couple of things I remember from the research are that cyberbullying very rarely originated using school equipment (cell phones were less of an issue at the time), but the targets and originators of cyberbullying typically involved students from the same schools. For this second reason, most assumed schools were in the best position to address the problem. The key point here is that bullying actions originated outside of schools (homes and homes of friends), but schools were in the best position to provide “educational remedies”. Some aspects of the cellphone and mental health issues are similar.

I see classroom use of cellphones as a convenience not that different from the use of laptops, chromebooks, or tablets. All devices could be used to access damaging or useful experiences. However, students would be in a supervised environment, unlike the situation in the home or other locations outside of the classroom. In allowing the use of phones (or other digital devices) teachers do not only monitor use, but have opportunities to focus on productive uses AND explore the damaging issues in a group setting.

You may not agree with my position, but I think the logic is sound and recognizes that phone use is far more frequently unsupervised outside of classrooms than within classrooms. It is easy to target schools and ignore the reality that parents are more likely to ignore what their children are doing on their phones for much longer periods of time. Experiences within schools are not the core source of problems that may exist.

The importance of a whole group experience also has two sides. Yes, if no student can use a phone in school then there are no haves and have nots. Nothing about this solves what happens outside of classrooms. Addressing the issues of what students experience online is going to be more consistent and probably effective when all students experience issues as part of a formal curriculum.

So, I don’t think banning phones in classrooms solves a mental health problem. I think the science on mental health and adolescence is still unclear. I disagree with what Haidt said in response to Swisher’s probing. His position eventually came down to “if it isn’t cellphones then what is it”. When there are positives and negatives associated with an activity (perhaps causally and perhaps not), simple solutions rarely produce a substantial advantage.

References:

Links are provided when possible. Other sources are cited below.

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The welfare effects of social media. American Economic Review, 110(3), 629-676.

Ferguson, C. J., Kaye, L. K., Branley-Bell, D., Markey, P., Ivory, J. D., Klisanin, D., Elson, M., Smyth, M., Hogg, J. L., McDonnell, D., Nichols, D., Siddiqui, S., Gregerson, M., & Wilson, J. (2022). Like this meta-analysis: Screen media and mental health. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 53(2), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000426

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.