I think of specialized note-taking tactics as approaches that go beyond the learner-controlled recording of text and maybe some basic sketches. These approaches involve some attempt to scaffold what I would describe as elaboration. I like to describe elaboration as a type of personalization that goes beyond recording information in a verbatim way involving summarization and/or the addition of examples or cross-references to other existing knowledge. A challenge here is the possible, working memory overload required to personalize the information input, and whether the circumstances of the presentation and capabilities of the individual learner allow the capacity for elaboration. The application of note taking while reading and listening to a presentation can be quite different because of differences in the opportunity to control the rate of input.

Popular examples of specialized tactics proposed for the K12 environment include Cornell notes, sketchnoting, and concept mapping. All involve either an extension or a rerepresentation of ideas from the content to be mastered. I will admit a bias in not being a strong advocate of any of these tactics with perhaps the most enthusiasm for the Cornell system. My reaction is mostly based on the increased demands on working memory these systems impose and whether the product generated in the case of sketch notes and concept maps is more useful longterm as a summarization.

For those wanting to investigate sketchnoting and the Cornell system here are some resources.

Sketchnoting video, Kathy Schrock’s sketch noting guide, and an engineering setting argued to benefit from educators at Iowa State (see references below).

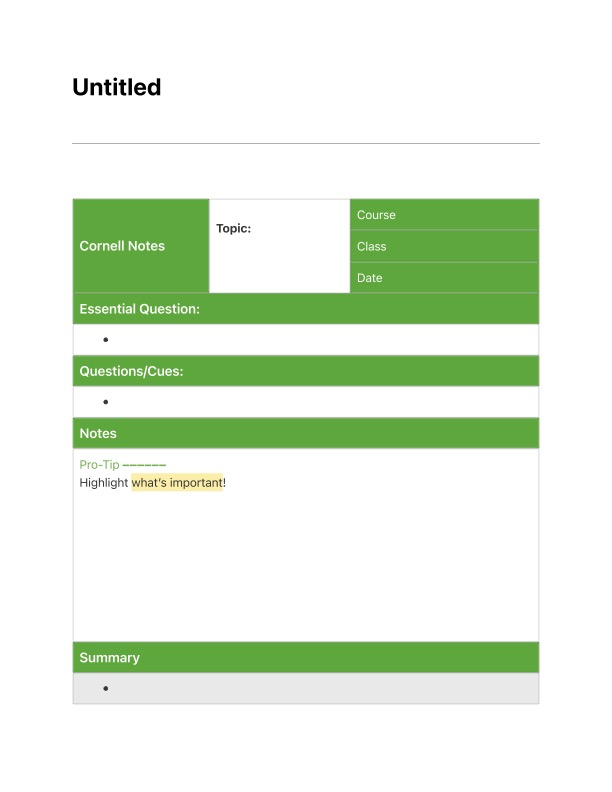

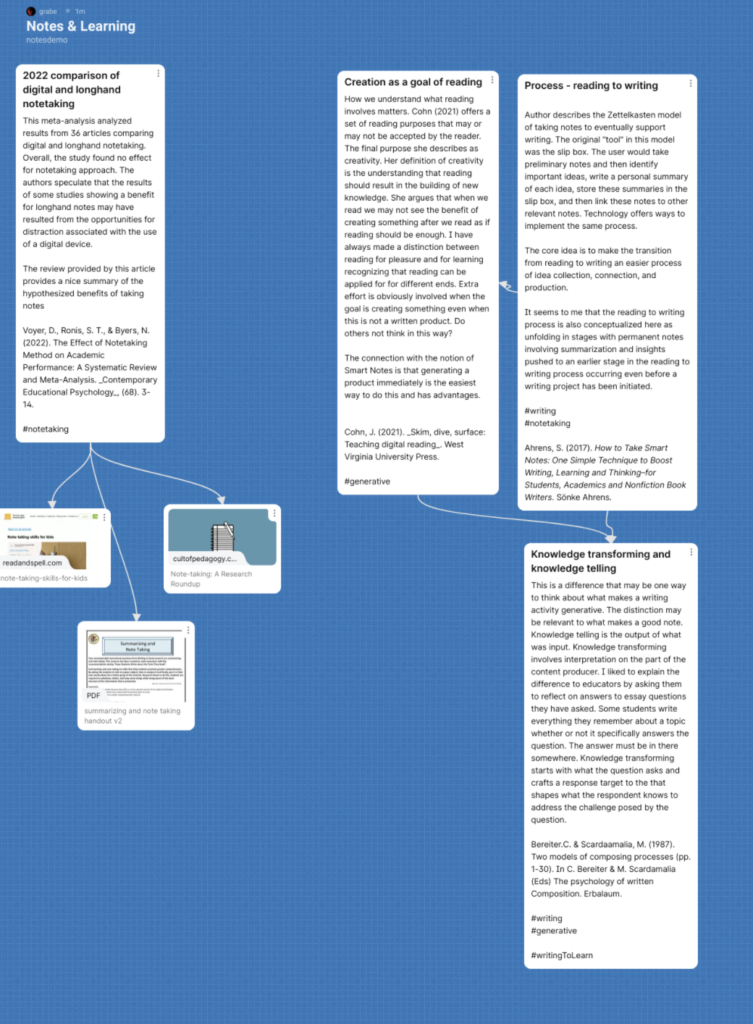

I use Evernote as an information archive. Evernote offers different templates and one is for Cornell Notes. The template offers a way to explain what I mean by a scaffold for personalization.

I have come to see note-taking as best understood as a three stage process (see references that follow). From this template, you can see how the middle stage – the after class or revision stage – would be applied. After taking notes and after class, you can generate a summary (bottom box) and generate questions (above the middle box). Developing a summary (something like Ahern’s Smart Notes) could involve elaboration. The questions could improve the effectiveness of review (study).

One final observation – I find it strange that there are so many carefully controlled research studies comparing taking notes by hand versus by a digital device and so few directly comparing these specialized note taking systems and traditional note taking.

References:

Chen, P. H. (2021). In-class and after-class lecture note-taking strategies. Active Learning in Higher Education, 22(3), 245-260.

Luo, L., Kiewra, K. A., & Samuelson, L. (2016). Revising lecture notes: how revision, pauses, and partners affect note taking and achievement. Instructional Science, 44(1), 45-67.

V. Paepcke-Hjeltness, M. Mina and A. Cyamani, “Sketchnoting: A new approach to developing visual communication ability, improving critical thinking and creative confidence for engineering and design students,” 2017 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), 2017, pp. 1-5, doi: 10.1109/FIE.2017.8190659.

105 total views

You must be logged in to post a comment.