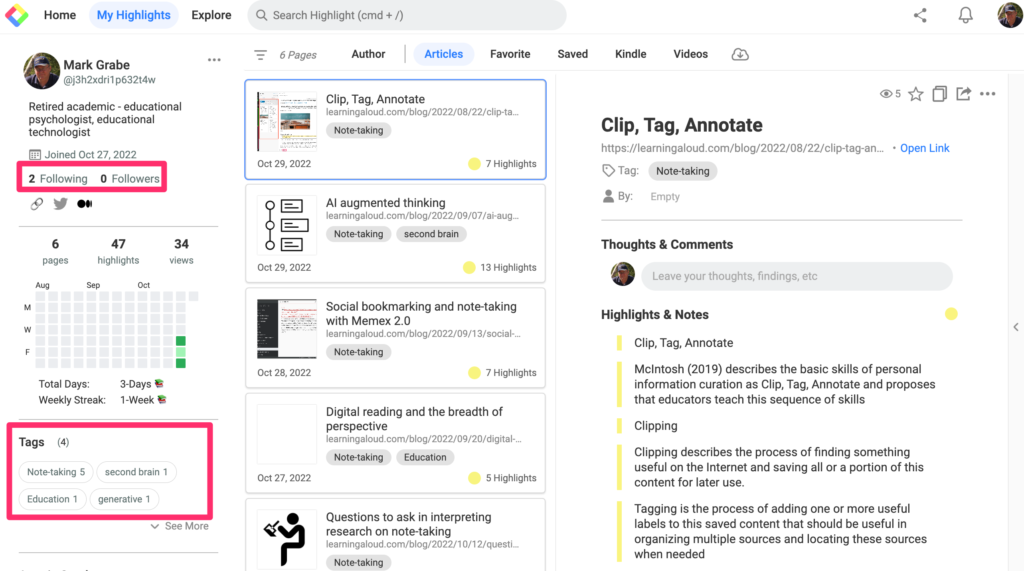

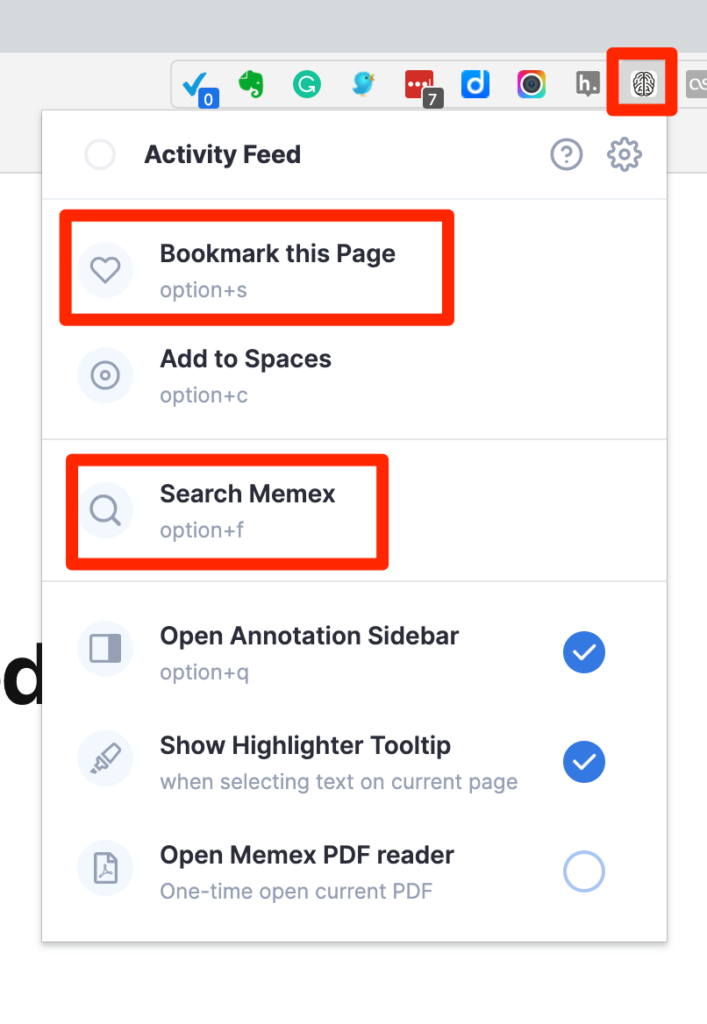

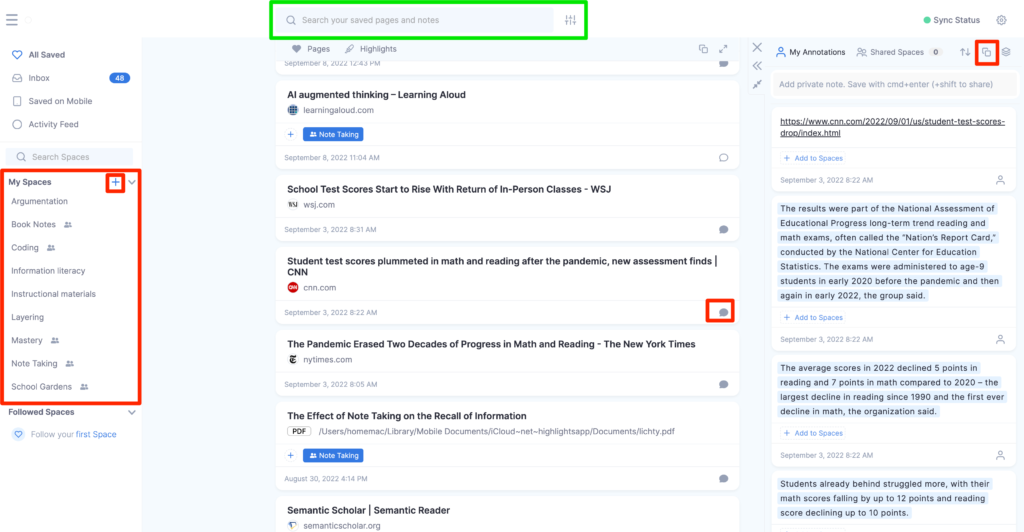

Some knowledge workers (writers) offer descriptions of their writing process using titles such as “How I work”. The benefit, I assume, is to provide others insights regarding the flow or process used by the author that might result in a beneficial adjustment to the reader’s own activity. I will begin by offering a general overview of the process I use and then will explain how the system works when I write based on a specific type of source material.

At the general level, I imagine what I am trying to do is to create bi-directional linkages between products. Those products include the original source material, stand-alone notes, and my original document that is intended to be shared with others. One additional goal in this process is important. I want to create sources in the process of writing that have value to me over time and not just for one project. By this, I mean I want the notes and original sources to be processed in such a way that I can easily use them to locate relevant information and to be more efficient to use for future projects. I make use of digital tools and digital information sources to achieve these goals.

Context

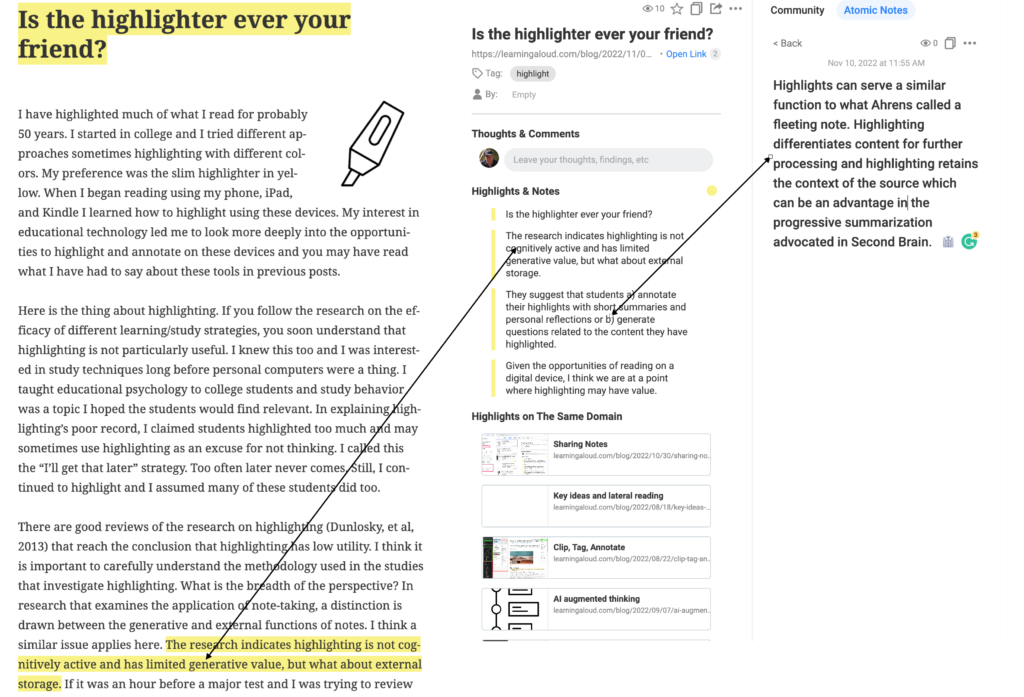

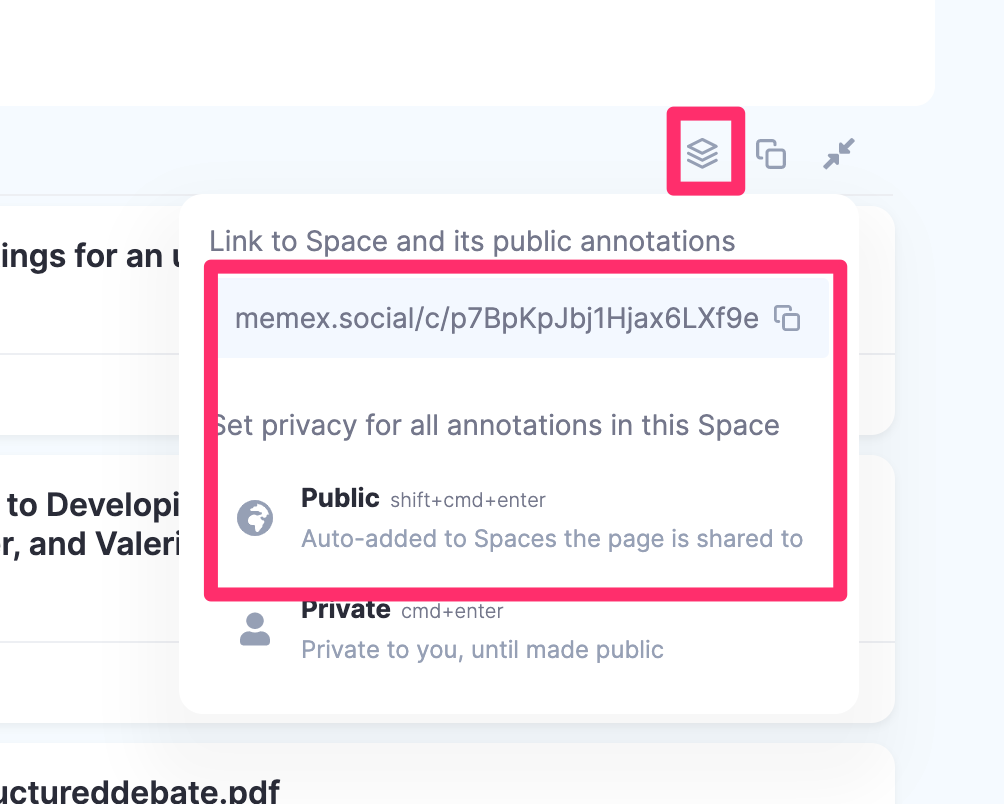

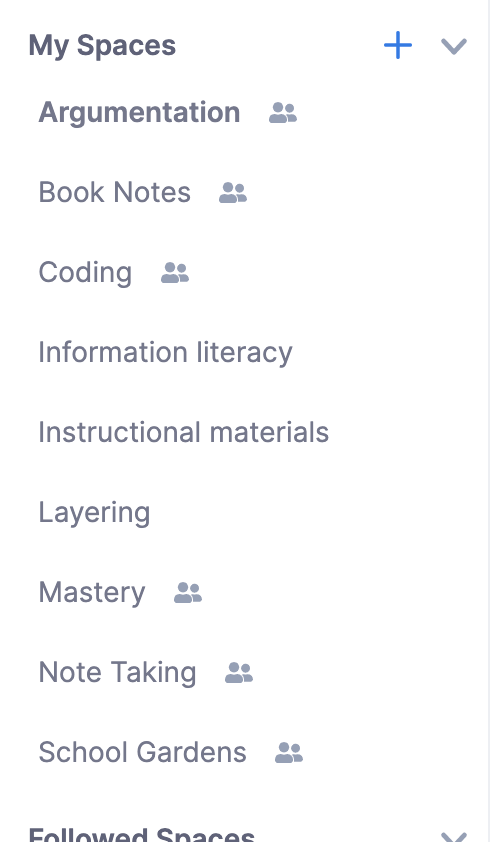

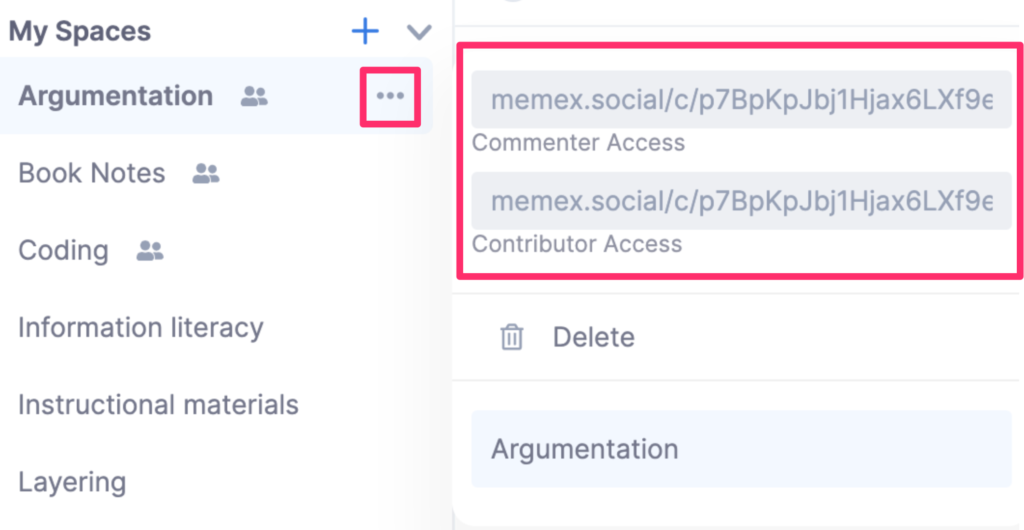

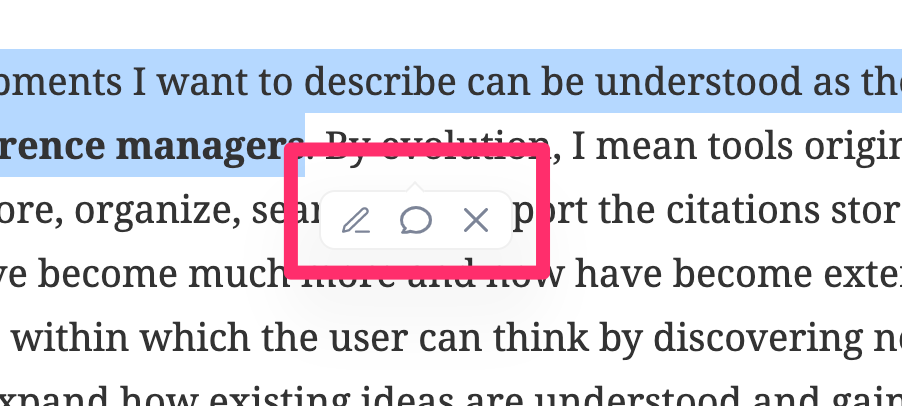

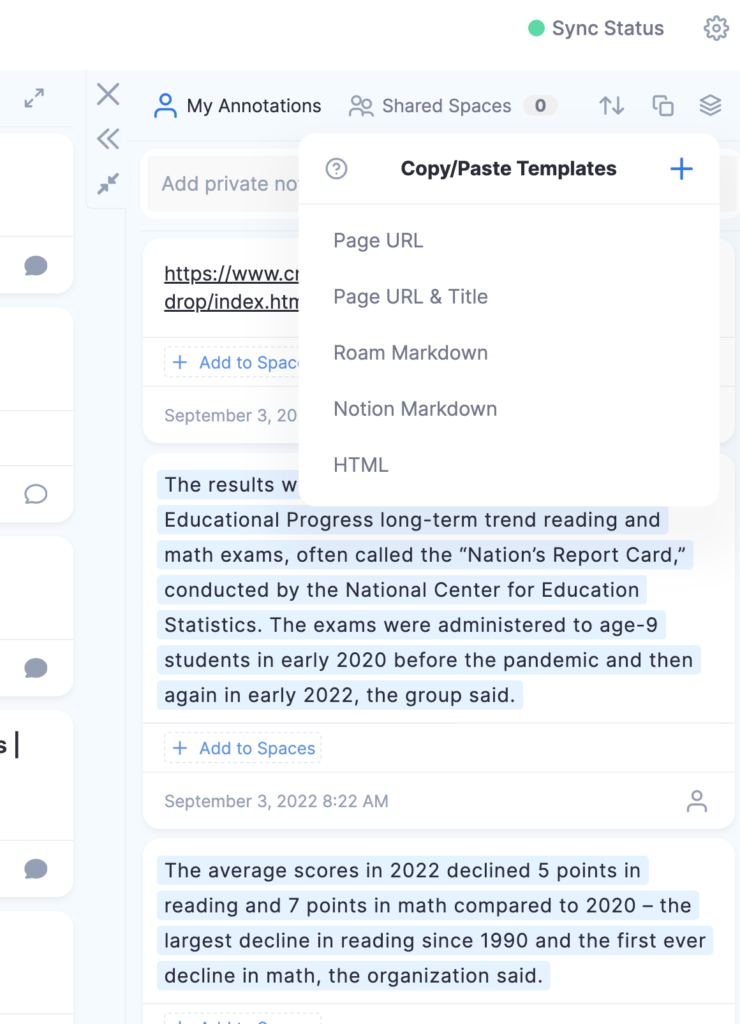

One concept that has proven useful in how I have come to think about and describe my workflow is that of context. The bi-directional linkages between products I have generated are constructed to maintain context. So, the original sources are highlighted and annotated when they are read. The highlights and notes exist within the context of the original sources. Some of these notes and highlights are extracted from these original sources to generate smart notes using a different digital tool. However, this extraction process includes links back to the original sources to maintain context. So, at a later point in time, the link associated with a smart note can be used to return to the original document and the location within this document associated with a smart note.

By the way, the definition of a smart note is an idea that is understandable on its own. So these notes which were created based on information obtained elsewhere are written so that they do not require the original source for understanding. This stand-alone capability does not mean that reviewing such notes at a later time would not prompt a return to the original source perhaps for additional information or clarification. This review can be useful. Finally, I use the Smart notes typically generated from multiple original sources to write a product (typically a blog post at this stage of my career).

Thinking about the sequence of written sources is kind of interesting. As one moves through the sequence, there is less reliance on the context of the previous source and a greater focus on my own interpretation and speculation.

Example – pdfs as sources

Much of what I write is based on journal articles that I have access to as pdfs downloaded from my library. I work within an Apple environment and I make use of iCloud as online storage I can access from my iPad and desktop computer. Because of the time invested in accumulating many annotated pdfs and other products over time, the use of iCloud provides me some measure of security for the products I generate. I do create backups for added security.

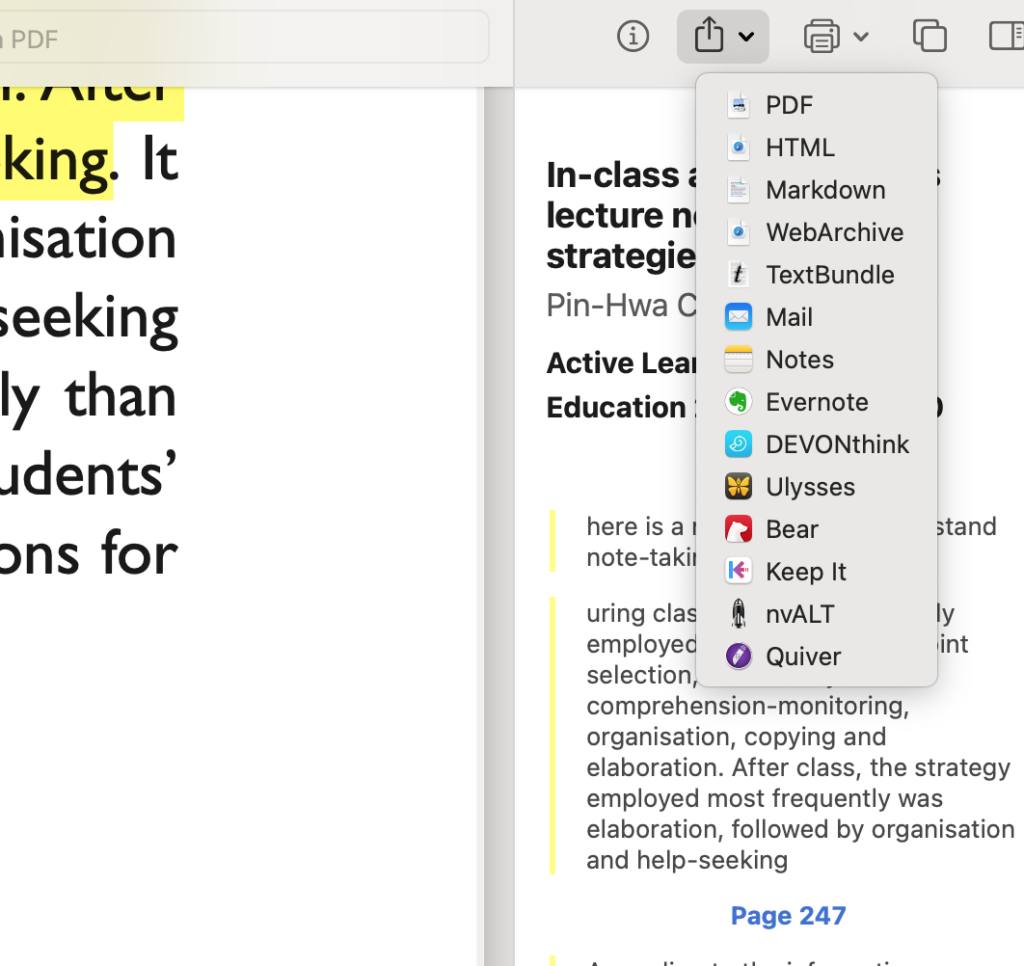

I first read the source pdfs using a digital tool. I have used Zotero, but I prefer a product specific to Apple called Highlights because it is less complicated to use and just seems more consistent. I mostly highlight while I read, but I also annotate when I know I want to create a Smart note from what I am reading.

Highlighting and annotation are processes that involve context as both processes connect a personal addition at a specific location within the source text. Both Zotero and Highlights allow highlights and notes to be exported as a file separate from the original pdf. There are options for the format in which this file is created and one is markdown. A markdown file is a text file that includes a few reserved text symbols that allow the content of the file to appear with headings and subheadings, links, tags, and other such features when opened with a tool that interprets the reserved markdown symbols. Markdown uses such symbols in a way similar to the symbols used in an HTML file. One of the core benefits of a markdown text file is that it will not eventually age out of usefulness. It is a text file and not a proprietary format so there will always be a way to open a markdown file and one does not have to worry about investing years in a tool that creates a file type that may not be useful if the tool is discontinued.

You get an idea of how Highlight works from the following image. The left-hand window shows the original pdf that has been highlighted. The highlights and notes that are added also appear in the right-hand panel and it is the content from this panel that is exported. The drop-down menu shows the various formats that can be used for export and you should find markdown near the top.

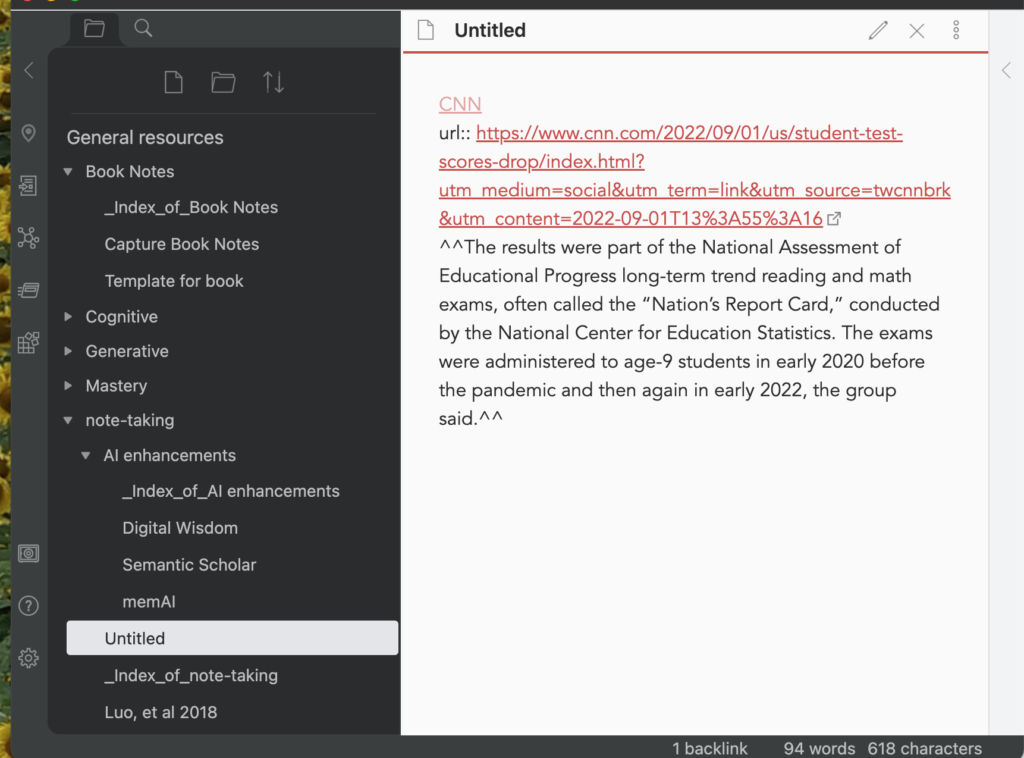

I use Obsidian to store the notes I create. Obsidian is a tool intended for organizing, cross-referencing, and tagging a large collection of notes for an extended period of time. It is a versatile tool, but I use it for storing citations and Smart notes. Obsidian works with markdown files and the content exported from Zotero or Highlights can be imported, manipulated, and stored in Obsidian.

Here is the useful capability I take advantage of when using these tools on my desktop computer. Having everything on the same machine is essential. Both Zotero and Highlights embed information about the location of highlights and notes within the original document. So, when a note is stored in Obsidian exported from one of these highlighting and annotation tools, a link will be included that will allow the Obsidian user to Zotero or Highlights and show the original text in which the highlight or note was embedded. Zotero is more specific and takes you to the exact location. Highlights takes you to the page rather than the specific location on the page.

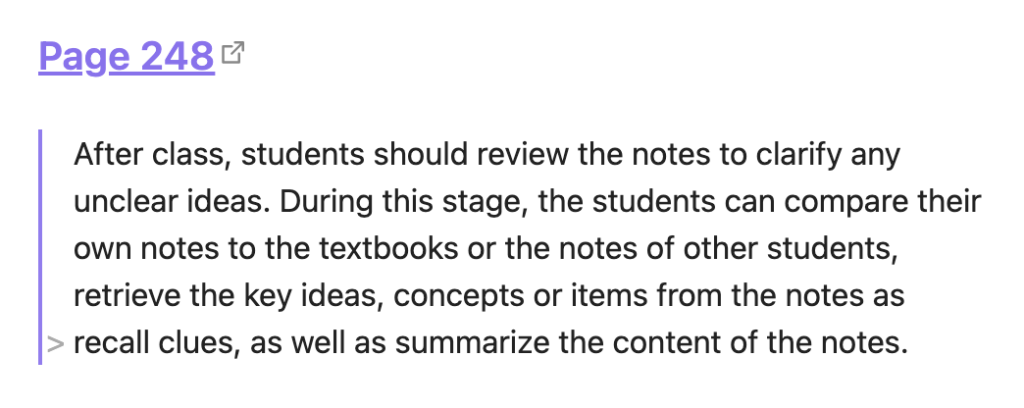

So, this is what a section of markdown might look like for a note (this from Highlights).

#### [Page 248](highlights://chen2021#page=4)

> After class, students should review the notes to clarify any

> unclear ideas. During this stage, the students can compare their

> own notes to the textbooks or the notes of other students,

> retrieve the key ideas, concepts or items from the notes as

> recall clues, as well as summarize the content of the notes.

When displayed in Obsidian, the note looks like this (see following image). If you look closely, you will see the link to the original pdf stored on my computer (and in iCloud). I typically add some additional information to my Obsidian notes (perhaps the full citation associated with a note). The second image below is more what of my Smart Note looks like. In this image, you can see I have added a tag (#contextualization) that serves several functions including allowing me to find other notes tagged in the same way.

As I write something like this blog post, I use mostly the notes I have saved in Obsidian. If I am using a specific source, I will include the citation for this source at the conclusion of a post and this citation would also allow me to work back through the sequence of products I have described to review both notes and locate the original document.

114 total views

You must be logged in to post a comment.