As we explore meaningful ways in which we can make use of the AI tools available to us at any given time, we must be aware of the limitations of AI and what the consequences of promoting the products we generate might be. My personal use of AI is to support the writing I do. This is what you are experiencing here. Misrepresentations would be embarrassing, but I write blog posts so the consequences at worst are not catastrophic.

I would not use AI to generate blog posts by entering a series of prompts to shape a product. What I want AI to do is to help me organize what I have learned and lessen the time spent translating the information I have collected into an external representation of my thinking. I use an approach that first requires me to read, highlight, and annotate sources (typically books and journal articles). Next, I export the residue of this process (the highlights and notes) into a tool that allows me to rework and connect these elements of information. Finally, I focused an AI tool on this content and prompted the tool to create a first draft product that fits some of the goals I have in mind. I use a series of technology tools in this process and I will identify several options for each stage I go through as this post unfolds. First, a couple of additional important concepts.

What I intend is a process focused on my personal decision-making and content vetting. As much as possible, I want to avoid AI hallucinations and I want to take advantage of my thinking and experiences while reducing the labor required to generate the words to externalize my thoughts. I also want to draw on concepts I might not recall at the moment of content creation but that take advantage of thinking I did at another point in time.

A couple of AI-related concepts that are important are Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and Source Grounding. RAG is a way of using AI to prioritize specified designated content in contrast to the massive summary of information used to train an AI model. I think of the goal in this way (my interpretation). I want an AI tool to use its language and communication capabilities to respond to my prompts. When possible, I want the tool to respond to my prompts using just the body of information I have provided. RAG is useful in several ways. Models are fixed at a specific point in time and new information may be available. The information used to train the model may be flawed or inaccurate relevant to a specific context of application and information can be prioritized to avoid the use of such an idea. My intent is related to this issue. I want the content produced to represent information and positions I support.

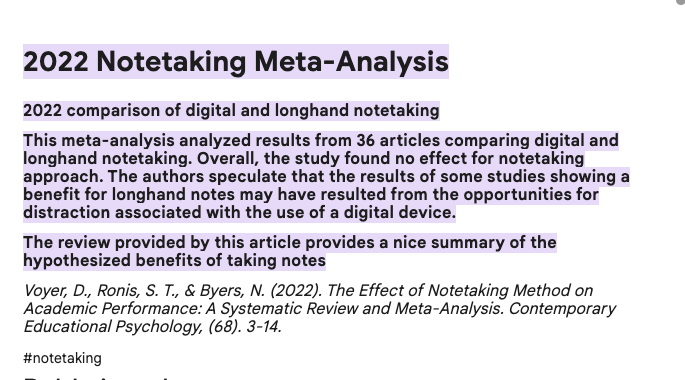

Source grounding is a similar issue but approached from the opposite direction. What sources were used by the AI tool to generate a specific part of the output? If you think in terms of notes and highlights, what was the section of highlights or the note associated with a given statement in the output?

This combination while not perfectly implemented in most tools, offers a reasonable way for an “author” to vet content they intend to take responsibility for sharing.

Specific tools and processes

Source material processing. Most of the information I write about I first encountered as a Kindle book or a journal article available to me as a PDF. I use tools to read and think about this material that allow highlighting and annotation and then the exporting of these notes and highlights containing metadata allowing identification of source and location from which the items were taken. Quantity is important here. I have a personal library of more than a hundred Kindle books and hundreds of journal articles. Kindle devices or apps allow both annotation and highlighting. I have used several pdf tools to do the same thing. Highlights is my present favorite. Again, what is essential is the opportunity to export the notes and highlights as a document I can then import for the next stage of the sequence.

Storage, post-processing, and retrieval. The popular term for describing the next stage of my process might be Second Brain. This is the notion that adults outside of a school environment have long-term learning needs – they learn something at one point in time and they could apply what they once learned after a considerable delay. Without external storage, what they once understood could easily be forgotten. What they once understood in a different context might still be useful if reworked for a different situation. Digital storage allows an external representation of what was once understood and encourages review activities encouraging new insights. Digital storage allows various approaches to search that can surface forgotten insights.

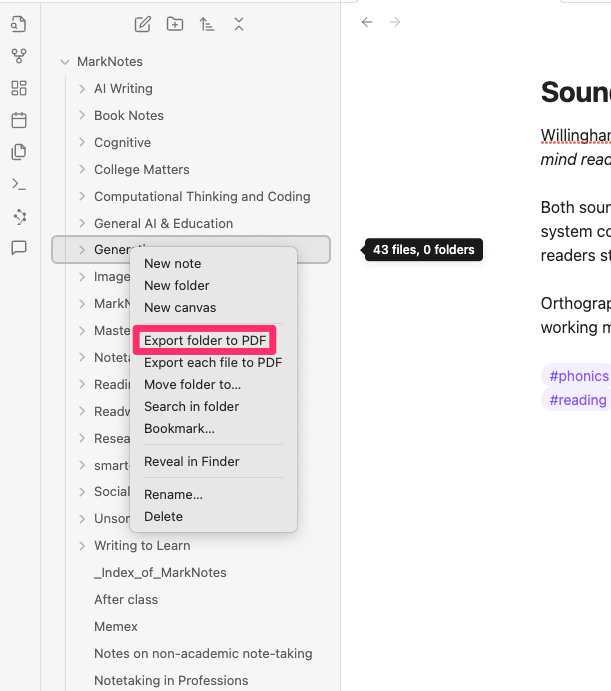

I have written frequently about the implementation of this concept. To keep things simple for this post, Obsidian is my tool of choice within this category. I can generate notes to be stored by this tool as I read. I can also copy and paste notes and highlights from other tools. ReadWise is a utility that makes this process even easier. It automatically downloads highlights and annotations I create while reading using Kindle and with an Obsidian plugin automatically checks for new highlights or notes and uploads these highlights and annotations to Obsidian. So, overtime my Second Brain grows both manually and automatically as I read.

3. Discovery, exploration, and first drafts. This is the point at which AI makes an appearance in how I get from reading and thinking to writing. Typically, second-brain advocates promote strategic exploration of second-brain content as the way to get to externalization through writing. Review your notes. Search for connections among your notes. Enter new notes based on these processes of review and connection. AI applications with RAG capabilities allow a user to explore the content they have identified in a different way. You can interact with this content directly and in a speculative way. You can propose requests for analysis or comparison. In my case, some of these highlights and notes are now at least five or more years old so sometimes I rediscover ideas that would not come to mind without this assistance. Tools that offer source grounding allow easy access to the specific pdfs and comments associated with a claim generated by the AI tool and make it easy to review the context and related arguments from the original sources. You can return to specific sections of material and consider it from a new perspective.

My hope is that the structure I offer here will encourage you to spend some time with the tools I identify. I have used the following AI tools and propose they are worth a try.

Smart Connections – an AI plugin for Obsidian

Copilot – used as an AI plugin with Obsidian

MEM.ai – an online note-taking and exploration tool with built-in AI capabilities

NotebookLM – an online note-taking and exploration tool with built-in AI capabilities

These tools are different in several ways that may be of interest. While Obsidian is an open source tool and so are the two plugins I have mentioned, the plugins require an OpenAI api that requires a subscription. I have found the use of this API is very inexpensive and far more so than the $20 a month plan for say ChatGPT. Obsidian is resident on your device. MEM.ai is an online service with a subscription price of a little over $8 a month when committing to the yearly plan. NotebookLM offers the easiest approach for source grounding and the other tools require playing with the prompt to get note titles and links. The automatic transfer of Kindle notes and highlights to the note-taking tool via Readwise only works for Obsidian. So, these AI tools will do similar things, but work in different ways with different financial costs.

Comparison with example

An example may make what I have described more concrete. Recently, I wrote a post comparing two books – The Anxious Generation and Unlocked – that offer very different perspectives on the dangers of screen time and social media to children and adolescents. I read both books generating highlights and notes and then wanted to write a post summarizing each and comparing the perspectives provided by he author. This post can be found on my blog.

I have since made use of the four AI tools I list here to generate a short first draft on this same topic. In each case, I used the following prompt:

Using my notes, write a 600 word comparison of how Haidt and Etchells describe the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health.

I include the output from the four tools here. They are similar, but for sake of completeness all have been provided should someone want to compare and contrast the products. Of course, such comparisons are inexact as the same tool would produce slightly different outputs should the tool respond to the same prompt several times. I don’t really expect anyone to read the multiple versions of output, but recommend you read the prefacing description of the tool to determine if that tool might fit your circumstances.

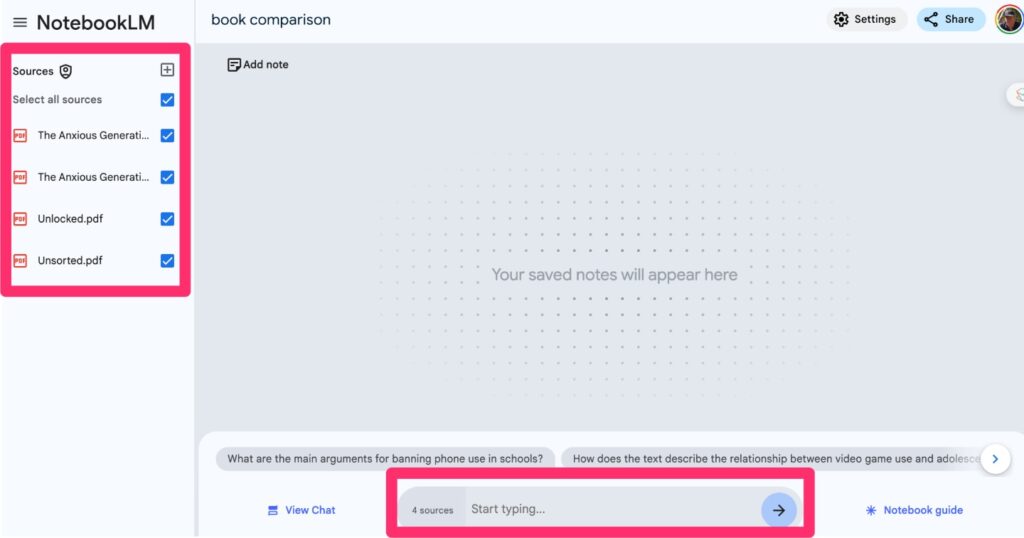

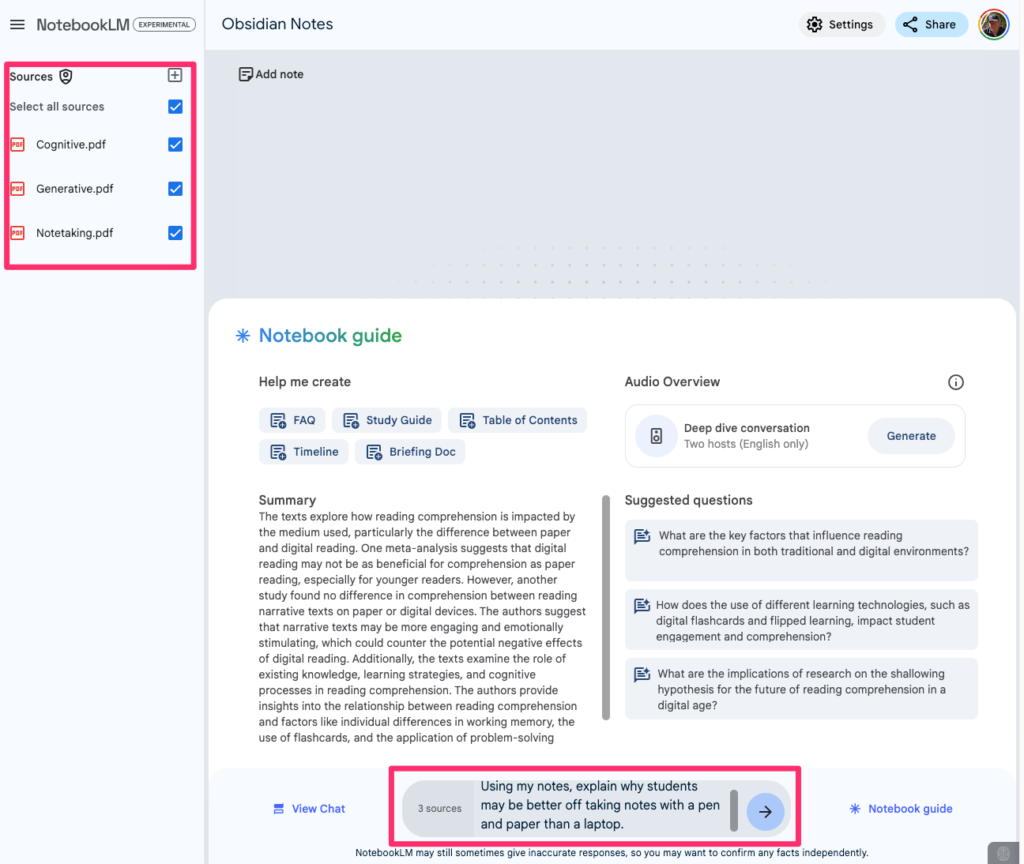

NotebookLM

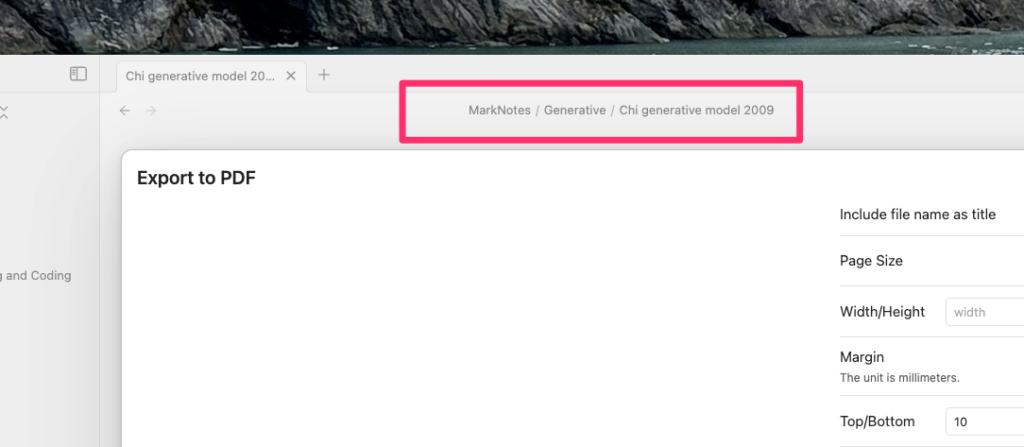

NotebookLM allows me to most easily demonstrate the combination of RAG and Source Grounding. The challenge within my workflow is moving content from Obsidian to NotebookLM. I have found a way to do this efficiently and explain this process in an earlier post.

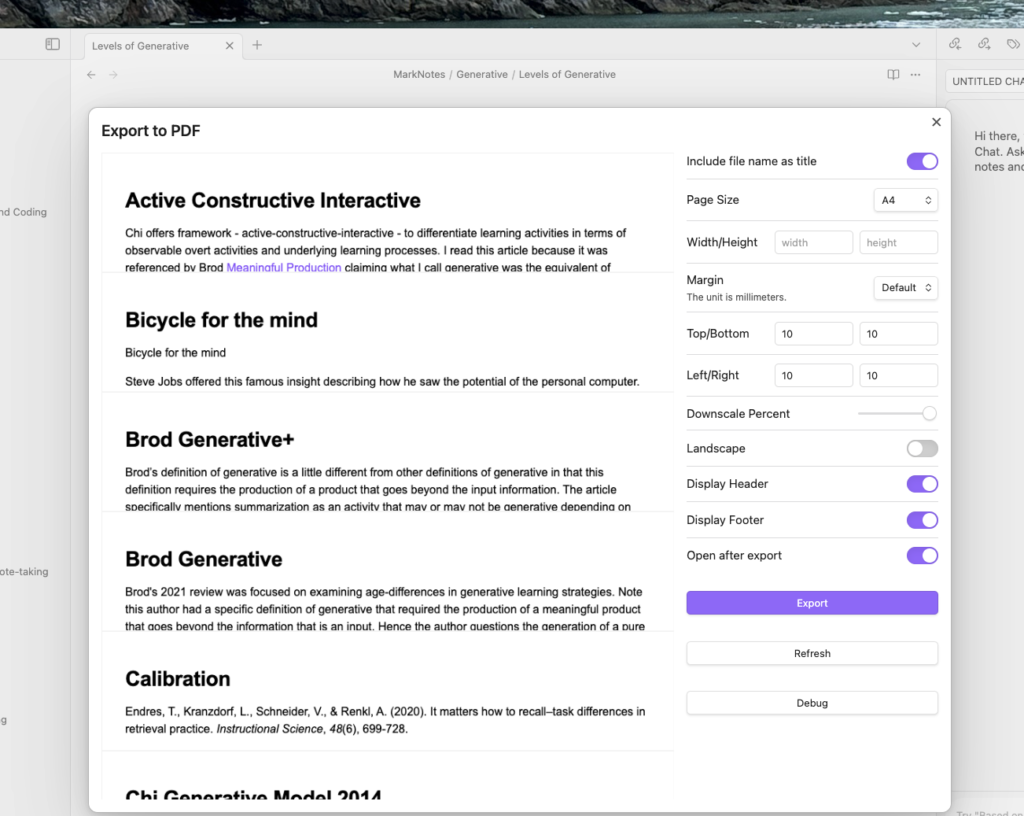

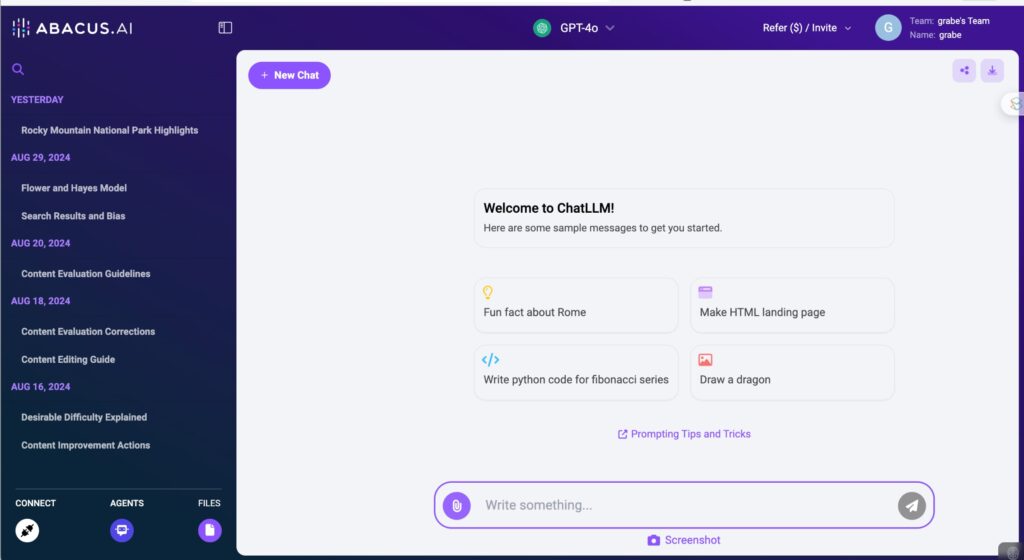

If you are unfamiliar with NotebookLM, the image that follows offers a peek at the interface. NotebookLM is a web-based tool so what is displayed is what would be seen within your browser. I have started a notebook for the specific goal of comparing my notes on these two books and I have already uploaded my collection of notes and highlights into NotebookLM. The left-hand column indicates that four sources have been added. The text box for entering a prompt to “chat” with these resources appears at the bottom of this image.

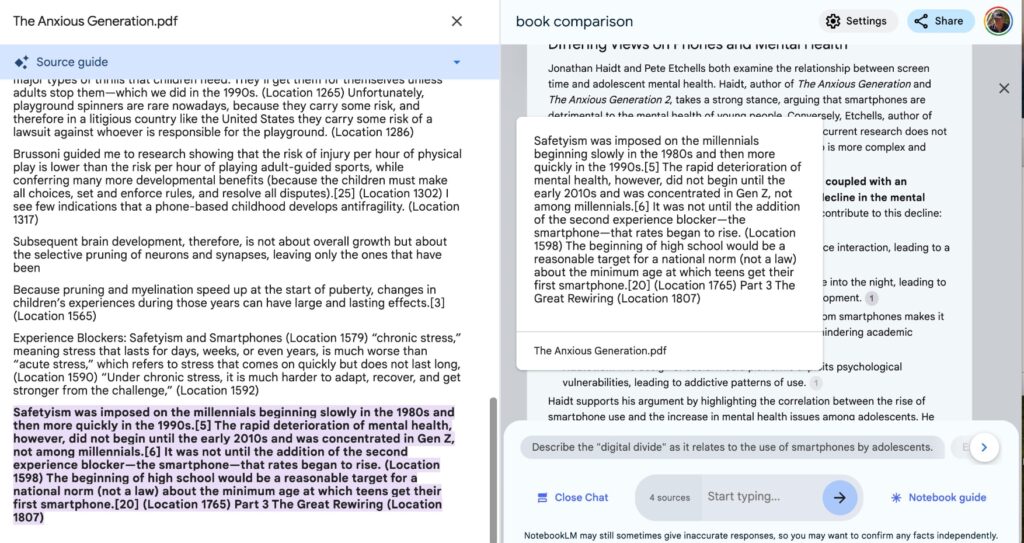

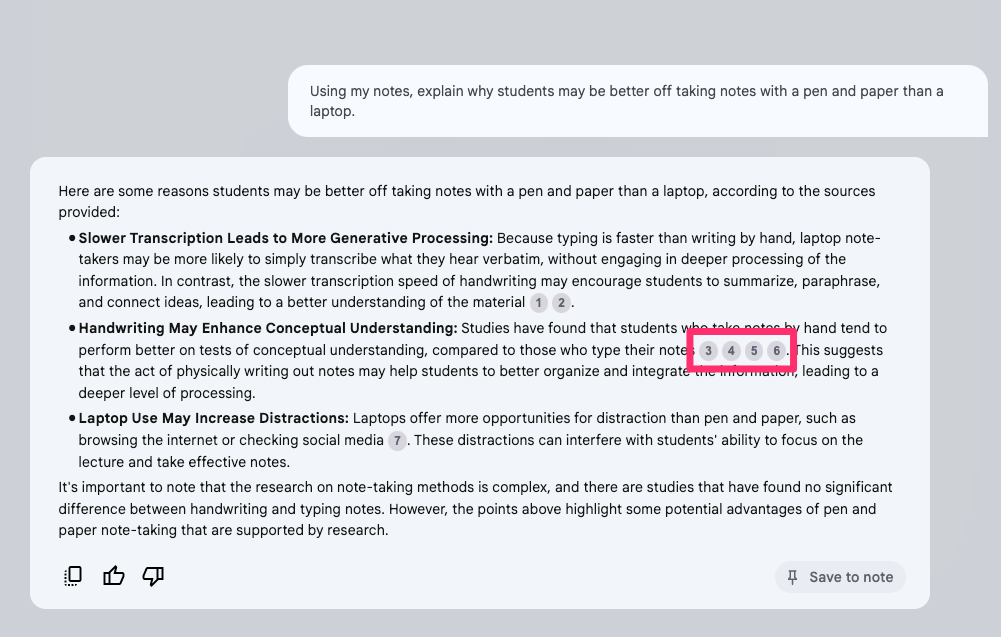

In response to the prompt, the AI capabilities of NotebookLM generates a response. The following image is complicated but shows multiple things. There is the response to the prompt which I will provide following the image. Within this content, you should see small numbers associated with different sections of the output text. These numbers when selected open a window showing the segment of the source content that was used by the AI system to produce the output. The connection of something specific from the source material with a claim made in the output is what I mean by source grounding. As you can see, I then have access to the source content and can explore the context of the designated material if I want to consider whether I agree with the interpretation made by the AI.

NotebookLM prompt response

Differing Views on Phones and Mental Health

Jonathan Haidt and Pete Etchells both examine the relationship between screen time and adolescent mental health. Haidt, author of The Anxious Generation and The Anxious Generation 2, takes a strong stance, arguing that smartphones are detrimental to the mental health of young people. Conversely, Etchells, author of Unlocked: The Real Science of Screen Time, believes that current research does not support this view, suggesting instead that the relationship is more complex and nuanced than commonly portrayed.

Haidt contends that the introduction of smartphones, coupled with an increasingly safety-focused upbringing, has led to a decline in the mental well-being of Gen Z. He argues that several key factors contribute to this decline:

- Social Deprivation: Smartphones supplant face-to-face interaction, leading to a lack of vital social skills development.

- Sleep Deprivation: Smartphone use often extends late into the night, leading to insufficient sleep, which is crucial for adolescent development.

- Attention Fragmentation: The constant stimulation from smartphones makes it difficult for adolescents to focus on tasks, potentially hindering academic performance and emotional regulation.

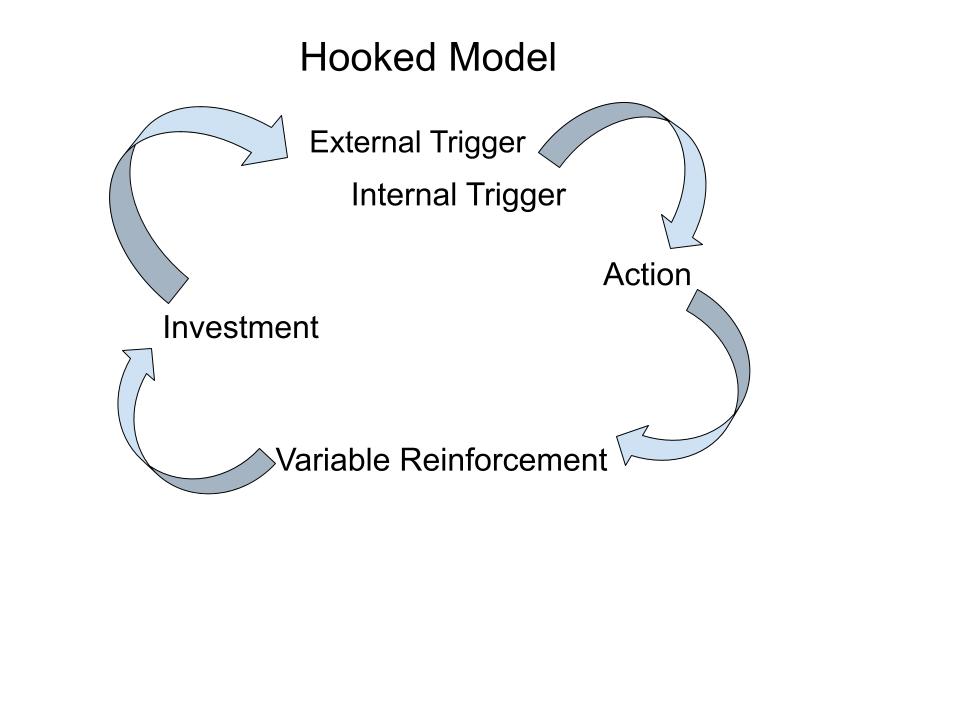

- Addiction: The design of social media platforms exploits psychological vulnerabilities, leading to addictive patterns of use.

Haidt supports his argument by highlighting the correlation between the rise of smartphone use and the increase in mental health issues among adolescents. He points to 2012, the year when Facebook acquired Instagram and rates of depressive episodes began to rise, as a pivotal moment in this trend. He emphasizes the importance of face-to-face, synchronous interaction for healthy emotional development, a type of interaction that social media platforms largely fail to provide. Instead, social media, with its emphasis on likes, shares, and followers, fosters conformity and potentially harmful social comparisons. Haidt is especially concerned about the impact of social media on girls, noting that the worst years for social media use for girls are between 11 and 13. He advocates for delaying smartphone ownership until high school and restricting social media use until age 16. He also argues for phone-free schools and more opportunities for unsupervised play, allowing children to take risks and develop resilience.

Etchells, however, cautions against drawing simplistic conclusions about the relationship between screen time and mental health. He argues that many studies linking smartphone use to negative outcomes rely on self-reported data, which can be unreliable and influenced by prevailing societal narratives about screen time. He points out that large-scale, longitudinal studies that track actual smartphone usage over extended periods are scarce, making it difficult to establish causal relationships. He also emphasizes the importance of considering the context of smartphone use, rather than focusing solely on the amount of time spent online. Factors such as the specific apps used, the purpose of use, and the social context of online interactions can significantly influence the impact of screen time on mental well-being.

Etchells critiques the use of anecdotal evidence and alarmist headlines in the media, arguing that such stories, while compelling, can distort public understanding of the issue. He suggests that focusing on developing healthy screen habits, rather than demonizing technology, is a more productive approach. He advocates for a nuanced understanding of screen time, acknowledging both its potential benefits and risks.

Both Haidt and Etchells agree that more research is needed to fully understand the complex interplay between screen time and adolescent mental health. While their perspectives differ in terms of the severity of the issue and the proposed solutions, both authors offer valuable insights into a topic of increasing societal concern.

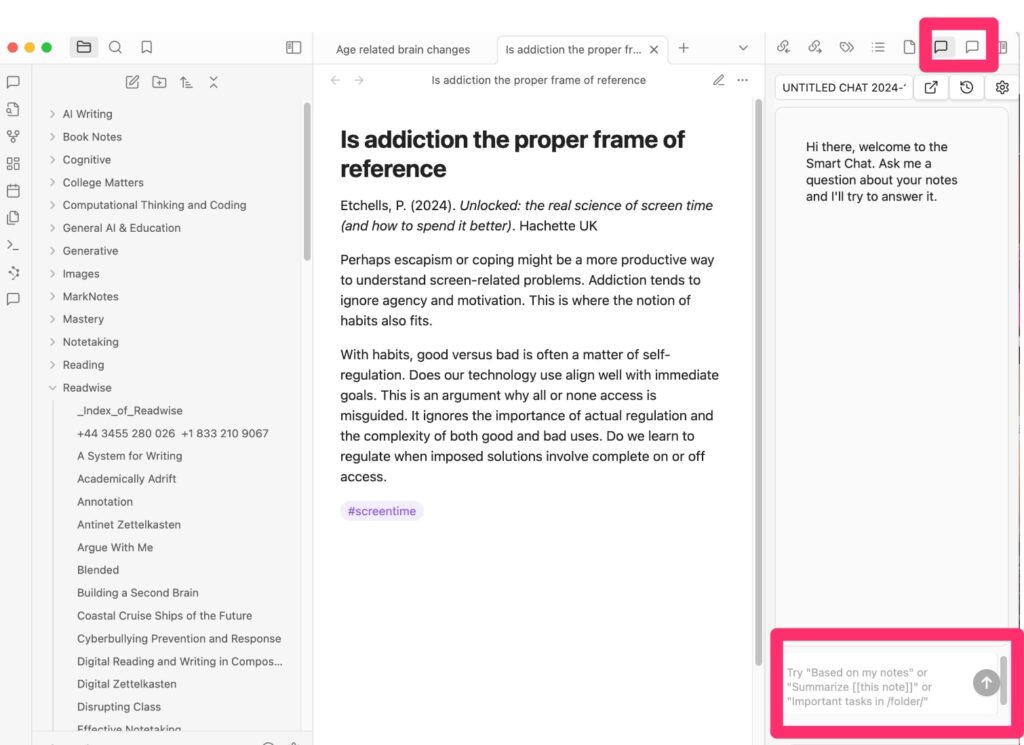

Smart Connections and Copilot

Smart Connections and Copilot are both plugins added to Obsidian and both rely on the OpenAI API (requires a subscription). It makes sense to simply suggest these plugins are options that do very similar things.

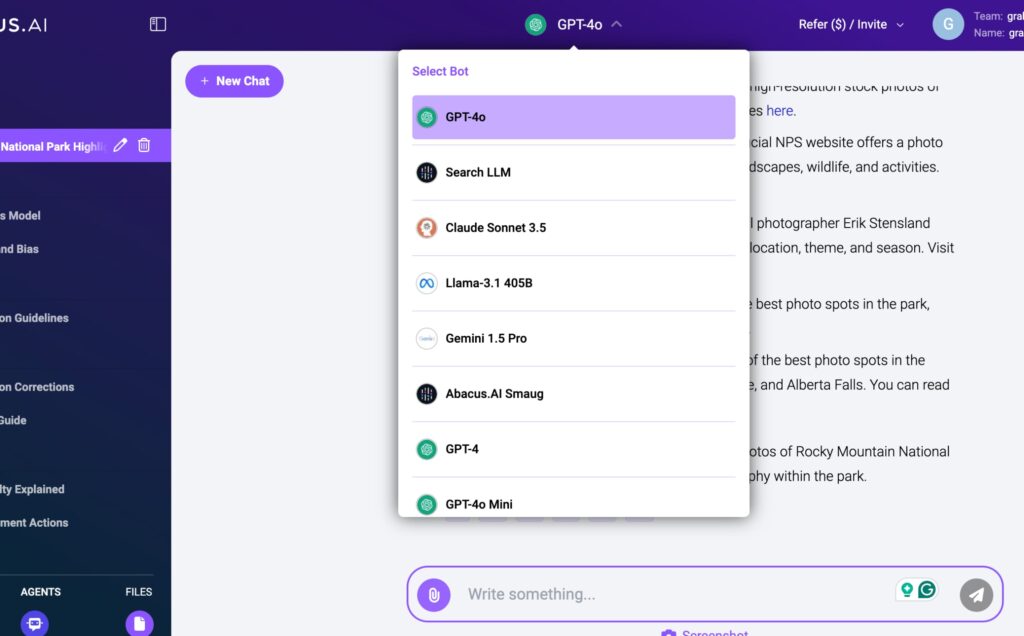

If you are unfamiliar with Obsidian, the following image is intended to show the basic functions. The left-hand (note folders) and middle column (a selected note) concern displaying, locating, and inputting notes. The right-hand column serves a variety of additional functions including accessing and using plugins. Two symbols in the red square at the top of this column allow the selection of either the Copilot or Smart Connections capabilities. The text box within the red square at the bottom is for the submission of a prompt to the AI plugin. The response to the prompt appears in the now vacant area above the prompt window.

Smart Connections Prompt Response

Based on your notes, Jonathan Haidt and Pete Etchells offer contrasting perspectives on the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health. Haidt, in his book “The Anxious Generation,” argues that smartphones and social media have contributed to a surge in anxiety and depression among young people, particularly focusing on the impact of the widespread adoption of technology in the late 2000s and early 2010s. He proposes solutions such as delaying smartphone and social media access until high school, implementing phone-free schools, and promoting unsupervised play to address the mental health challenges faced by adolescents.

On the other hand, Etchells, in his book “Unlocked,” challenges the common narrative surrounding screen time and mental health. He argues that the issue is more complex than simply quantifying screen time and emphasizes the importance of how individuals engage with technology. Etchells suggests that some screen time can be beneficial and urges readers to reflect on their screen habits, considering factors such as content consumed, apps used, and context of use. He encourages a more thoughtful and intentional approach to technology use to support and improve mental health.

Haidt’s perspective is supported by research indicating a negative correlation between social media use and life satisfaction, particularly among younger adolescents. He highlights key dates associated with changes in technology, such as the introduction of iPhones in 2009 and the acquisition of Instagram by Facebook in 2012, correlating with a significant upturn in depressive episodes among Gen Z around 2012. Haidt’s argument is further reinforced by the addictiveness of social media, which exploits users’ identities and impacts emotional development.

In contrast, Etchells challenges the notion that screen time is a key driving factor behind the decline in mental health. He emphasizes the need to focus on how individuals engage with technology rather than solely measuring screen time. Etchells suggests that understanding and reframing screen habits, reflecting on behaviors, and being critical of information can help individuals leverage technology to support their mental well-being.

Overall, while Haidt highlights the detrimental effects of smartphone and social media use on adolescent mental health, Etchells offers a more nuanced perspective, advocating for a shift in focus towards healthy screen habits and intentional technology use. Both authors contribute valuable insights to the ongoing debate on the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health, providing readers with different perspectives to consider when addressing this complex issue.

CoPilot Prompt Response

To write a comprehensive comparison of how Jonathan Haidt and Tim Etchells describe the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health, we need to delve into their respective perspectives and analyses. Both authors have explored this topic, albeit from different angles and with varying emphases

Jonathan Haidt’s Perspective

Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist, has extensively researched the impact of social media and smartphone use on adolescent mental health. Haidt argues that there is a significant correlation between increased smartphone use and the rise in mental health issues among adolescents, particularly anxiety and depression. He often cites statistical data and longitudinal studies to support his claims, pointing out that the surge in mental health problems coincides with the widespread adoption of smartphones around 2012.

Haidt emphasizes the role of social media platforms in exacerbating feelings of inadequacy and social comparison among teenagers. He suggests that the curated nature of social media content leads adolescents to constantly compare themselves to others, which can result in negative self-perception and increased anxiety. Furthermore, Haidt highlights the addictive nature of these platforms, which are designed to capture and hold users’ attention, often at the expense of real-world interactions and sleep, both crucial for mental well-being.

Tim Etchells’ Perspective

Tim Etchells, on the other hand, approaches the topic from a more nuanced and perhaps less deterministic angle. While acknowledging the potential negative impacts of smartphone use, Etchells is more focused on the context and manner in which these devices are used. He argues that smartphones are not inherently detrimental to mental health; rather, it is the way they are integrated into daily life that matters.

Etchells emphasizes the importance of digital literacy and the need for adolescents to develop healthy habits around technology use. He suggests that when used mindfully, smartphones can offer significant benefits, such as fostering connections, providing access to supportive communities, and serving as tools for creativity and self-expression. Etchells is more likely to highlight the potential for positive outcomes, such as increased access to mental health resources and the ability to maintain relationships across distances.

Comparative Analysis

When comparing Haidt and Etchells, several key differences emerge in their analyses of the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health. Haidt tends to focus on the negative consequences, often presenting a more cautionary tale about the pervasive influence of smartphones and social media. His approach is data-driven, relying heavily on empirical evidence to underscore the risks associated with excessive use.

In contrast, Etchells offers a more balanced view, acknowledging both the potential harms and benefits of smartphone use. He advocates for a more individualized approach, considering the diverse ways in which adolescents engage with technology. Etchells is more optimistic about the potential for positive outcomes, provided that there is an emphasis on education and the development of healthy digital habits.

Both authors agree that there is a relationship between smartphone use and mental health, but they diverge in their interpretations and proposed solutions. Haidt calls for more stringent regulations and societal changes to mitigate the negative impacts, while Etchells focuses on empowering individuals through education and awareness.

Conclusion

In summary, Jonathan Haidt and Tim Etchells provide contrasting yet complementary perspectives on the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health. Haidt’s analysis is rooted in caution and concern, highlighting the potential dangers and advocating for systemic changes. Etchells, meanwhile, offers a more hopeful outlook, emphasizing the role of education and personal responsibility in navigating the digital landscape. Together, their insights contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of this complex issue, underscoring the need for a balanced approach that considers both risks and opportunities.

MEM.ai

I started Mem.ai because it was from the beginning a note system that incorporated AI. I had to manually upload the notes I entered in Obsidian. Mem.ai proposed that the linking and tags advocated as so important in Obsidian were less necessary when one could apply AI capabilities to explore the stored notes. There seemed some logic to this proposal and I wanted to see what I thought after using both systems.

MEM.ai Prompt Response

Certainly! Let’s delve into a comparison of how Jonathan Haidt and Pete Etchells describe the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health, using insights from your notes.

Comparing Perspectives: Haidt vs. Etchells on Adolescent Phone Use and Mental Health

The discourse surrounding adolescent phone use and its impact on mental health is a complex and multifaceted one. Jonathan Haidt and Pete Etchells offer distinct perspectives on this issue, each bringing unique insights into how digital technology influences the well-being of young people. While Haidt presents a more cautionary view, Etchells provides a nuanced analysis that considers both risks and benefits.

Haidt’s Perspective: A Warning on Digital Dangers

Jonathan Haidt, a prominent social psychologist, has been vocal about the potential dangers of smartphone use among adolescents. His perspective is largely shaped by the following points:

1. Correlation with Mental Health Decline: Haidt highlights a significant uptick in mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, among teenagers starting around 2011. He correlates this trend with the rise of smartphones and social media, suggesting a causal link between increased screen time and deteriorating mental health.

2. Social Media’s Role in Psychological Distress: Haidt argues that social media platforms exacerbate feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem, particularly among adolescent girls. The constant exposure to curated images and the pressure to gain social validation can lead to harmful comparisons and social anxiety.

3. Gender-Specific Vulnerabilities: Haidt emphasizes that adolescent girls are especially vulnerable to the negative effects of social media. He attributes this to the heightened focus on appearance and social comparison, which are more pronounced in female social media interactions.

4. Advocacy for Restrictive Measures: To combat these issues, Haidt advocates for delaying smartphone use among children. He suggests policies like “No smartphones before high school” to reduce exposure to potentially harmful digital environments and promote healthier developmental outcomes.

Etchells’ Perspective: A Balanced Approach

In contrast, Pete Etchells offers a more balanced view of the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health. His analysis considers both the potential risks and the benefits of digital technology:

1. Empowerment through Connectivity: Etchells acknowledges that smartphones and social media can empower adolescents by providing access to information, educational resources, and supportive communities. This connectivity can foster a sense of belonging and enhance self-efficacy.

2. Importance of Digital Literacy: Etchells stresses the role of digital literacy in helping adolescents navigate the online world safely. By equipping young people with critical thinking skills and the ability to manage their digital presence, they can mitigate potential negative impacts.

3. Balanced Screen Time: Rather than advocating for strict limitations, Etchells promotes a balanced approach to screen time. He suggests that integrating both digital and physical activities can help adolescents develop a healthy relationship with technology.

4. Focus on Resilience and Adaptation: Etchells believes that with proper guidance, adolescents can develop the resilience needed to thrive in a digital world. By fostering emotional intelligence and critical thinking, young people can learn to navigate the challenges of social media and smartphone use.

Contrasting Approaches to Solutions

While both Haidt and Etchells recognize the significant impact of smartphone use on adolescent mental health, their approaches to addressing these challenges differ:

Restrictive vs. Empowering Solutions: Haidt’s approach is more restrictive, focusing on limiting exposure to technology as a means of protecting mental health. In contrast, Etchells emphasizes empowerment through education and digital literacy, advocating for a more nuanced understanding of technology’s role in adolescents’ lives.

Focus on Risks vs. Opportunities: Haidt’s narrative centers around the risks and negative outcomes associated with smartphone use, particularly for adolescent girls. Etchells, however, highlights the opportunities for empowerment and connection that technology can provide, suggesting that the benefits can outweigh the risks when managed appropriately.

Conclusion: Navigating the Digital Landscape

The contrasting perspectives of Haidt and Etchells underscore the complexity of the relationship between adolescent phone use and mental health. While Haidt’s concerns about the negative impacts are valid, Etchells’ emphasis on empowerment and education offers a hopeful path forward. Ultimately, the key lies in finding a balance that maximizes the benefits of technology while mitigating its risks, equipping young people with the tools they need to thrive in an increasingly connected world.

This comparison captures the essence of both authors’ views, providing a comprehensive look at their differing approaches to adolescent phone use and mental health. If there are specific points you’d like to adjust or expand upon, feel free to let me know!

—-

My goal is to offer some options you might consider. I find advantages and disadvantages with each approach and still use a couple of these tools when I think the first one could be improved.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.