The benefits and harms done by our devices and the ways we use them is one of those topics likely of at least marginal interest to most people. We wonder whether we have become too dependent and whether existing interests and capabilities have deteriorated. If we are a parent or educator we likely have additional unique interests. Have I messed up my kid by letting him or her use a phone without supervision? How do I keep my students on track in the classroom and are they using AI to complete my assignments quickly without any actual educational benefits?

My personal interest goes a bit further in that I spent my career preparing educators to use technology in their classrooms and I by training feel responsible for understanding the science behind recommendations made to others. So, I review the research on many topics. From this perspective, I would offer the following observation – it is seldom as simple as it seems. I know this to be true in the social sciences which would be the field covering phone use and the impact on development and learning. This is the case for many reasons and far from a topic I can thoroughly consider here. One comment I used to make to my own students may be helpful. For context, I was trained as a biologist who became a psychologist. My comment was – students tend to see a discipline like chemistry as more sophisticated and complicated than psychology. Consider that the chemicals in that beaker don’t decide whether they feel like reacting today. People are different.

Back to the issue of our devices and the research on how we are being impacted. I recently read a book by Jonathan Haidt titled The Anxious Generation. Many people must have read this book because it topped the New York Times best-seller list for several weeks which I interpret to mean many parents and educators are concerned and were attracted by the topic. Recommendations made in the book, for example, no phones in schools, have been implemented in many schools. I read Haidt’s book in response to such changes concerned my pro-technology advocacy should be tempered. I admit my initial reaction was that Haidt made a reasoned and evidence-based case. However, I have learned that such secondary sources need to be vetted and I was concerned by some of Haidt’s rationale which I would describe as “what else besides iPhones and Instagram” could explain the mental health issues of adolescent females. The “what else could it be” logic just seems weak. In reaction, I read a related, but less well-known book by Pete Etchells and as I suspected the issue is complicated.

What follows is my summary of the two books with some related comments.

Comparing Perspectives on Screen Time and Mental Health

Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation”

In “The Anxious Generation,” Jonathan Haidt really covers two broad problems he contends have changed the mental health development of children and adolescents. Children have been overprotected in their daily lives resulting in a lack of play and autonomy involving risks and consequences. In contrast, the author argues that the rise of smartphones and social media have been largely unmonitored and unrestricted with negative consequences to mental health. I will comment on both claims, but emphasize technology use.

Haidt highlights the following key points:

Slow-Growth Childhood: Human children have an extended childhood compared to other mammals, providing them with time to learn through play and social interactions. This extended childhood is crucial for emotional and cognitive development.

Importance of Play: Play-based childhoods are essential for healthy development, fostering skills such as emotional regulation, social competence, and creativity.

Safetyism: Haidt argues that the overprotective parenting style prevalent in the 1990s, termed “safetyism,” limited children’s opportunities for risk-taking and independence, further contributing to anxiety. Haidt uses example older folks will find familiar – e.g., playground equipment that is no longer allowed for safety reasons and reduced independence in moving about the neighborhood or in solo trips to the store.

Negative Impacts of Smartphones: These problems include:

Social deprivation: Replacing face-to-face interaction with screen time.

Sleep deprivation: Late-night phone use cutting into sleep at ages when necessary. The early school start for adolescents is an example of when this becomes a problem.

Attention fragmentation: Constant notifications and multitasking impairing focus.

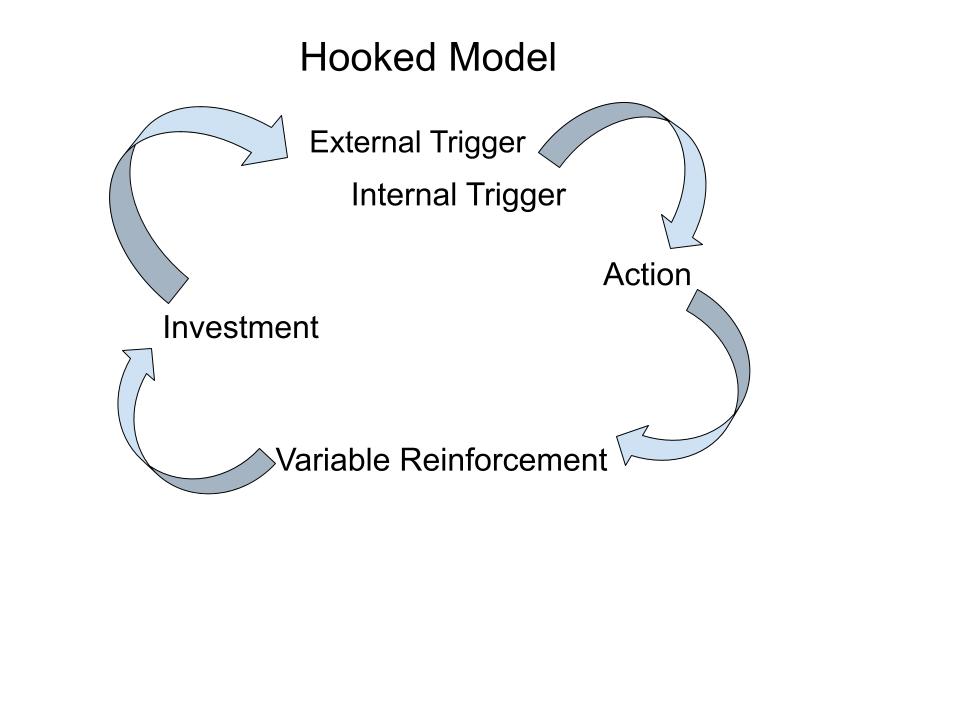

Addiction: The design of social media platforms promoting addictive behaviors. Etchells will reject this notion if understood as a physiological addition as in drug use.

Puberty as a Sensitive Period: Puberty is a critical period for brain development, making adolescents particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of social media. Hence, experiences allowed at other ages may do less damage.

What evidence suggests that puberty is a “sensitive period” for social media use?

Brain Development: Puberty to a greater degree than the earlier period of childhood involves the pruning of neurons and the strengthening of connections, processes influenced by experiences. This heightened neuroplasticity implies that experiences during puberty, including social media use, can have a greater and more enduring impact on brain structure and function.

Orben’s Research: Amy Orben, found that negative correlations between social media use and life satisfaction were more pronounced in the 10-15 age group, encompassing puberty, compared to older individuals (16-21). This finding directly supports the idea of puberty as a sensitive period for social media’s influence on well-being.

Social Learning and Conformity: Adolescents are conformers, a process that social media platforms can strongly influence. Puberty marks a time when individuals are particularly sensitive to social cues and peer influence, seeking to establish their identity and social standing. Social media platforms, with their emphasis on likes, followers, and influencers, can hijack this natural drive for social learning, potentially leading to distorted perceptions and unhealthy comparisons. Giirls are most vulnerable to social media’s negative effects between 11 and 13, while boys experience this heightened vulnerability between 14 and 15. This timeframe aligns with typical puberty onset, further suggesting that the hormonal and social changes during this period make adolescents more susceptible to the pressures and comparisons prevalent on social media.

In conclusion, the sources provide converging evidence pointing to puberty as a “sensitive period” for social media use. This sensitivity stems from the interplay of rapid brain development, heightened social awareness, and the drive for conformity, all characteristic of adolescent development. This information suggests that social media use during puberty requires particular attention and potentially different approaches compared to other age groups.

Haidt makes use of historical data linking changes in mental health data over the years to changes in the technology available to young people. Much of Haidt’s argument about the damage done by access to the Internet is made by tracking mental health outcomes against dates associated with changes in technology. Gen Z started to reach puberty in 2009. iPhones became available in 2009. Social media capabilities such as retweets and likes became available in 2009. Front facing cameras in 2010. Facebook acquired Instagram in 2012. His challenge to critics is what else could have accounted for the changes in adolescent mental health that correspond to this time frame.

Recommendations: Haidt proposes four solutions to address this issue: no smartphones before high school, no social media before age 16, phone-free schools, and promoting more unsupervised play and childhood independence.

Etchells’ “Unlocked”

Pete Etchells, in his book “Unlocked: The Real Science of Screen Time (and how to spend it better)” offers a more nuanced view of screen time and its relationship to mental health.

Etchells first notes that the consequences of technology and social media likely include both positive and negative impacts so explanatory models must take into account both possible outcomes. Etchells’ key arguments include:

Screen Time is Complex: Etchells argues simply measuring the total amount of screen time is insufficient to understand its impact on well-being. What matters is how screen time is used, the specific apps and content consumed, and the context of use.

Limited Evidence for Strong Negative Effects: While some studies have shown correlations between screen time and mental health issues, the evidence is mixed, with many studies showing small or inconsistent effects. The existence of correlations even if the correlation reflected a causal relationship with negative changes in mental health as a consequence do not necessarily show large effects. The impact is typically small.

Etchells critiques the reliance on anecdotal evidence and highlights methodological limitations in much of the research. One of the most important methodological limitations appears to be whether self-reports versus verifiable behavioral data are used. Even though digital devices are great at recording data on use (consider your iPhone and your daily report of time spent on different apps) many studies ask users to estimate their time spent and activities experienced. When studies using self-report data are compared with studies using the more accurate data collected by the devices used, significant relationships are typically found only with the self-report data. Etchells speculates that user awareness of screen time issues and potential negative consequences results in participants in these studies interpreting negative personal experiences as an indication of too much screen time. How individuals feel about their screen use and their perceived self-control are more strongly related to well-being than objective measures of screen time.

Importance of Habits over Addiction: Etchells argues that framing excessive screen use as “addiction” is unhelpful, as it focuses on abstinence as the only solution. Instead, he advocates for viewing screen use as a set of habits that can be modified to promote well-being. The author argues that the assumption of a physiological explanation (probably dopamine) within the framework of addictions such as drug abuse is what readers of many of the negative books assume. Addiction tends to ignore agency and motivation. This is where the notion of habits also fits and solutions that are more nuanced with a focus on decision-making and awareness.

Oversimplification of “Screen Time”: Etchells argues that simply measuring the total amount of time spent in front of screens is too crude a metric to be meaningful. He emphasizes that “screen time” encompasses a vast range of activities, from educational apps to social media to video games, each with potentially different effects on well-being. He contends that focusing solely on duration ignores the crucial factors of content, context, and purpose of use.

Reliance on Anecdotal Evidence: Etchells criticizes the prevalent use of anecdotal stories to support claims about the negative impacts of screen time. While these stories can be compelling and relatable, he argues they often lack scientific rigor and can lead to biased conclusions. We like stories because we often can relate to such examples and do not necessarily make the same connections with the data in graphs and statistics. Of course, coming up with examples that fit a perspective does not necessarily fit what is most common in a sample of participants. He points out that reliance on anecdotes is particularly problematic in a relatively new field like digital technology research, where robust, longitudinal data is still limited.

Methodological Issues in Correlational Studies: Much of the research on screen time relies on correlational studies, which can only demonstrate associations, not causal relationships. Etchells highlights the problem of “third variables,” unaccounted-for factors that might influence both screen time and mental health, leading to spurious correlations. For example, pre-existing mental health conditions, family dynamics, or socioeconomic factors could contribute to both increased screen time and negative well-being outcomes, creating the illusion of a direct link where none exists. Correlations showing relationships do not necessarily convey the magnitude of an effect. A significant correlation in a large population may be associated with a very small impact.

Lack of Theoretical Framework: Etchells argues that the field lacks a robust theoretical framework to guide research and interpret findings. He suggests that without clear theoretical models, researchers are left to “grasp at straws,” making tenuous connections between screen time and a wide range of outcomes without a solid foundation for understanding the underlying mechanisms. This lack of theoretical grounding makes it difficult to develop testable hypotheses and draw meaningful conclusions. Haidt’s “what else could it be” argument fits here.

Ambiguous Terminology: Etchells points out the imprecise use of terms like “addiction” and “attention” in screen time research. He criticizes the tendency to label excessive screen use as “addiction” without sufficient evidence of a true physiological dependence. He also argues that “attention” is often used interchangeably with “self-control,” leading to conceptual confusion and misinterpretations of research findings.

Insufficient Attention to Positive Effects: Etchells argues that the focus on potential negative consequences of screen time has overshadowed research on its potential benefits. He acknowledges that excessive or problematic screen use can be detrimental, but he emphasizes the importance of recognizing the many ways in which technology can enhance learning, communication, and social connection. He encourages a more balanced approach that considers both the positive and negative aspects of screen time.

In conclusion, Etchells urges caution against drawing sweeping conclusions about the impact of screen time based on the existing research. He advocates for more nuanced investigations that consider the complexities of technology use, adopt rigorous methodologies, and develop strong theoretical frameworks to guide future research.

Comparing Haidt and Etchells

While both Haidt and Etchells acknowledge the potential downsides of excessive screen time, they differ significantly in their overall perspectives and conclusions:

Emphasis on Negative Effects: Haidt emphasizes the negative impacts of smartphones and social media, attributing a rise in mental health problems directly to these technologies. Etchells, on the other hand, acknowledges the potential for harm but argues that the evidence for strong negative effects is weak and often overstated.

Role of Social Media: Haidt sees social media as a particularly harmful force, promoting conformity, comparison, and addiction. Etchells recognizes these potential issues but maintains that social media can also have positive benefits, depending on how it is used. The existence of both positive and negative outcomes argues against simplistic abstinence/avoidance and urges more careful personal awareness and control.

Solutions: Haidt proposes strict limitations on smartphone access and social media use, advocating for a return to a more play-based childhood with less adult supervision. Etchells focuses on promoting healthy screen habits, emphasizing individual agency and self-regulation rather than strict restrictions.

Conclusion

Haidt’s “The Anxious Generation” presents a compelling, albeit alarming, argument about the potential downsides of technology for young people. However, Etchells’ “Unlocked” offers a more balanced perspective, urging caution against oversimplifying the complex relationship between screen time and mental health. The key takeaway is that understanding the nuances of screen use and focusing on developing healthy habits is crucial for mitigating potential harms and maximizing the benefits of technology. Both books highlight the importance of critical thinking and evidence-based approaches when evaluating the impact of technology on our lives.

Sources:

Etchells, P. (2024). Unlocked: the real science of screen time (and how to spend it better). Hachette UK

Haidt, J. (2024). The anxious generation: How the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. Random House.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.