I have written about my interest in the Brave browser and ecosystem several times. It is not my interest here to repeat my previous comments and I would refer those interested in a complete description and more information about how to use the ecosystem to this post from the Mercury News [https://www.mercurynews.com/2019/07/26/magid-2/amp/]. You can certainly use the search box available through this blog to find some of my previous posts.

I am writing again because Brave has addressed one of the concerns I have expressed previously. A quick description is necessary to explain what I think has been improved. Brave offers both a way to block the collection of personal information intended to focus the later display of ads AND a way to subsidize content providers when the ads that might provide them a small source of revenue with income are blocked. My complaint was that users of Brave could block ads, but not make the effort to contribute money to compensate content creators. It was complicated to contribute money because you have to offer funds and make the effort to convert these funds into a type of cryptocurrency. It was challenging enough to do this to discourage non-geeks to make the effort.

What Brave has changed is to provide users of the browser to view ads through Brave to generate revenue for themselves. This provides a way to accumulate income within the ecosystem that can be accessed by the user (I think), but can also be used to compensate content producers. I have no idea how many take advantage of each option, but Brave makes the effort to encourage sharing with content producers and for now this seems a move forward.

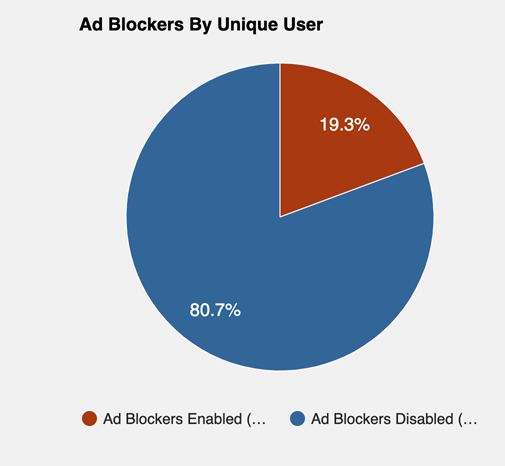

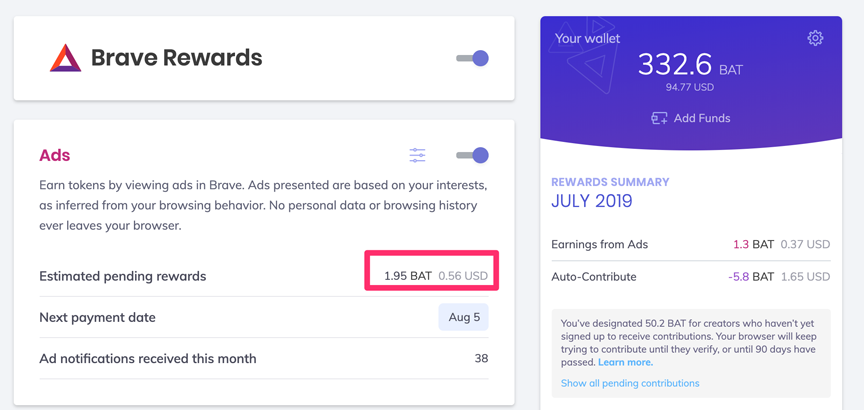

My story is this. I originally figured out how I could convert money into BAT (the cryptocurrency) and added $50. Strangely, I got in early and the value of this stake increased to nearly $100 as a function of the fluctuation of the value of BAT. I allocated 20 BAT a month to be distributed among the various sites I visit and view without ads. I also enrolled by site (https://learningaloud.com) so my resources were authenticated within the Brave ecosystem. I do have ads on some of my content, but I receive very little in revenue. I make the effort because I am curious about how this all works. For example, I know that about 20% of those who visit my site block the ads. This seriously underestimates exposure to ads as those who use a cell phone to view responsive content do not see the side bar which is where my ads are positioned. I estimate that less than 20% of views actually contain an ad.

I have had enough experience now with Brave to make some observations. I set my interest in viewing ads at two per hour. One limitation of the present version of Brave is that the data from multiple devices is not combined and iOS is not included in ad revenue generation. I generate personal ad revenue only when working on my desktop machine.

So, I am writing this on July 29 and you can see how much revenue I have generated from viewing Brave ads (56 cents or 1.95 BAT). With less than a week less in the month, you can kind of estimate how much I presently generate in a month. Again, I contribute 20 BAT per month.

You can participate in the Brave program without actually putting any of your money into the system. You can also accumulate BAT by accepting Brave ads. I interpret Brave to suggest that if you accept BAT for viewing ads, you should spend some of your income in support of those who are content creators. At least this is a start.

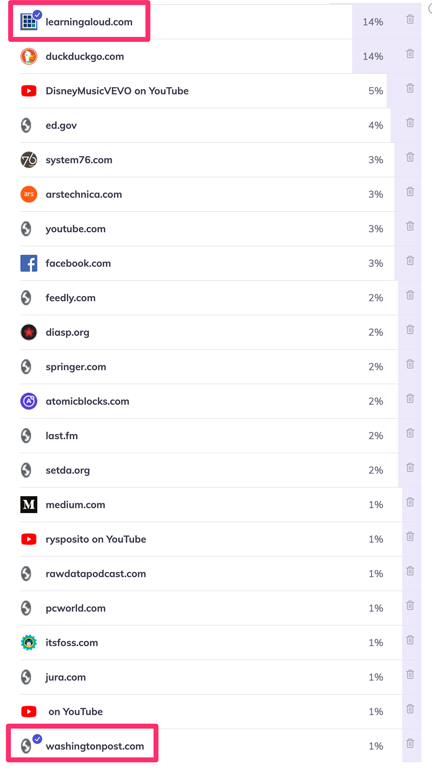

Here is one issue. Few content and service providers have made the effort to register with Brave. Registration is important in supporting this innovation and I urge everyone who falls into the category of content creator to make this effort. In the following image, I captured as much as I could from my screen. You see the gap between the list of sites I have visited and how few are registered. Yes, I end up paying myself, but this is a function of the sites I work on.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.