Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) and the focus on note-taking have generated many new applications. At this point, I think that significant advances in leveraging notes for personal productivity will come from AI, sharing, and a combination (AI identifying connections between personal notes and shared notes). I have written about AI applications in a previous post.

My emphasis here is on some note-sharing services I have explored. I will first identify some of the issues I think are important in committing to a service and then will present several sharing services. It is not feasible to cover the many options for sharing, but the services I describe should serve as a starting point for others and should offer some issues to consider.

Issues

1. What content are you interested in using as sources for your notes? My personal situation involves web content, pdfs, Kindle books, and ideas that pop into my head. Services may not cover all of these sources. For example, I am a retired academic and as a consequence continue to read and use journal articles (research studies) in guiding my thinking and writing. At this point, I read journal articles by downloading pdfs from my University library. I want to highlight and annotate these pdf and then connect the ideas I discover. A similar source for me is digital books (Kindle). The point – the services I list differ in which of these sources they easily integrate. Some services, surprisingly, don’t allow you to just generate a note from scratch but are focused on saving content for existing sources.

One side note – I have had interactions with developers related to sharing content from Kindle books (highlights). I wondered why you could view your own highlights within a service and yet not share these highlights. I thought it was about copyright concerns and they suggested this was true,. I suggested that if this was the case, they should at least allow notes taken to be shared.

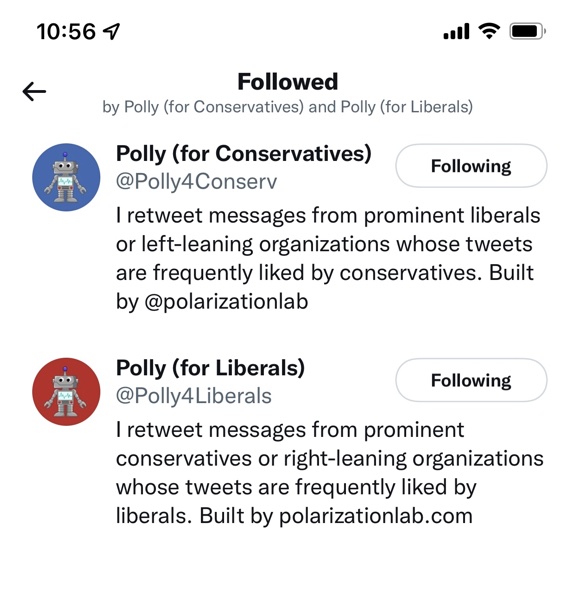

2. Social sharing requires social connections. How do you get from your personal involvement with a service to finding others with relevant information? Are you expected to find people outside of the service and talk them into joining and then connecting with you? This is kind of a “bring your own group” approach. This may be what you want. It is not what I need. I retired from my university job five years or so ago. My interests have changed since that time and I no longer have colleagues interested in these new topics I can encourage to interact with me through a social service. Does a service have a way to identify others with interests I can describe who might be willing to share with me? This is presently a big issue for me.

3. Cost – what are you willing to pay for a sharing service? Are you willing to pay anything? Would you be willing to pay after an opportunity to try a service and perhaps develop the connections necessary to make a service effective for you?

Examples (organized by the length of time I have used)

I have used Diigo for a long time and pay $40 a year for the premium service. Most of my Diigo content is public so you can take a look. Diigo can be used as a browser extension to save highlights and notes from web pages. It can work with pdfs. Probably the most unique function allows the transfer of highlights and notes directly for the online storage of Kindle notes and highlights. A newer function allows the population of an outline by dragging content from annotations and notes.

With the educational option of Diigo, I can create a group and share annotated bookmarks to that group. Google offers ways to find others with interests you may find relevant. I admit I have found these methods difficult to apply (try “search by sites”).

Memex is under development and yes it is still a service I have used for the second most time. Memex uses a browser extension to allow highlighting and annotation of web content. It allows annotation of pdfs that are stored locally so what is available for social sharing are the highlights and notes only. Kindle annotations cannot be moved directly to Memex, but an intermediary such as Readwise can fill in this gap if important. This would require an additional paid subscription.

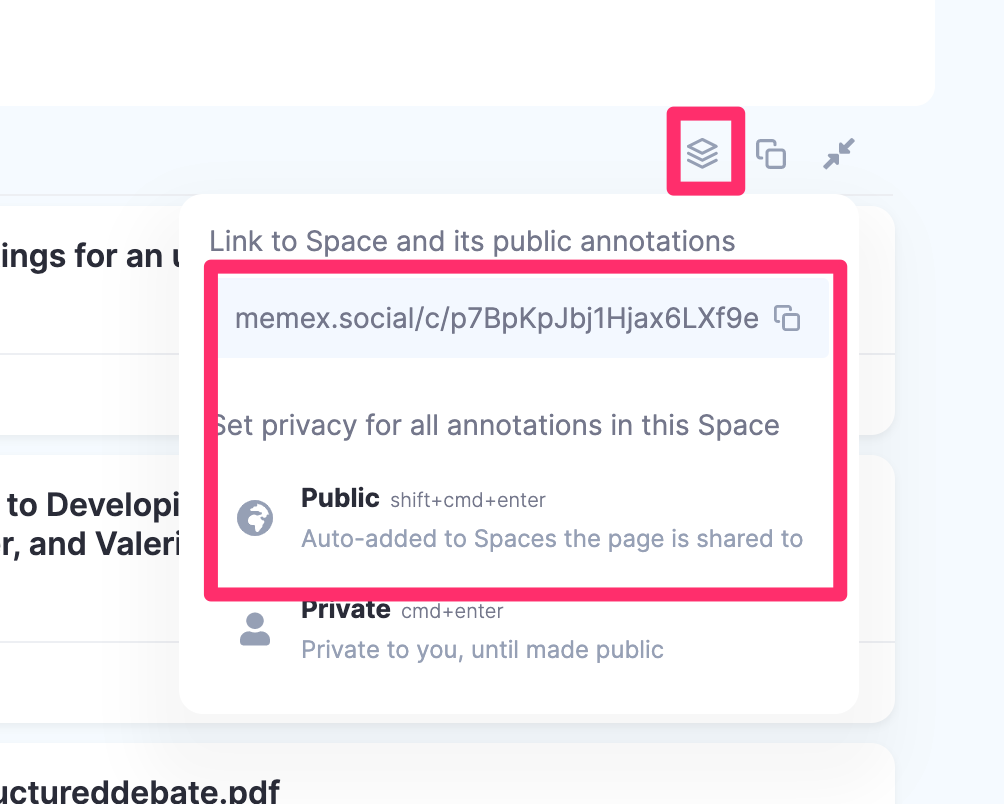

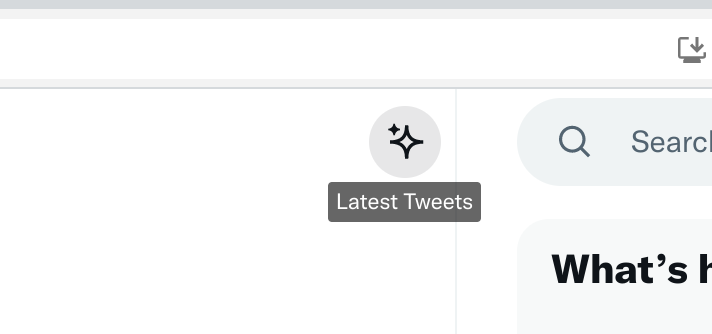

You can share individual notes or thematic collections (Spaces). The following image should the icon used to display a single note and the link that is then generated to share.

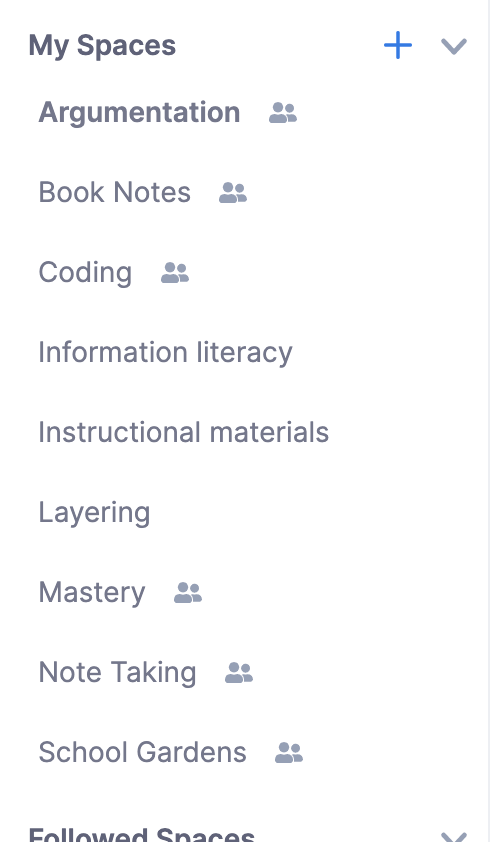

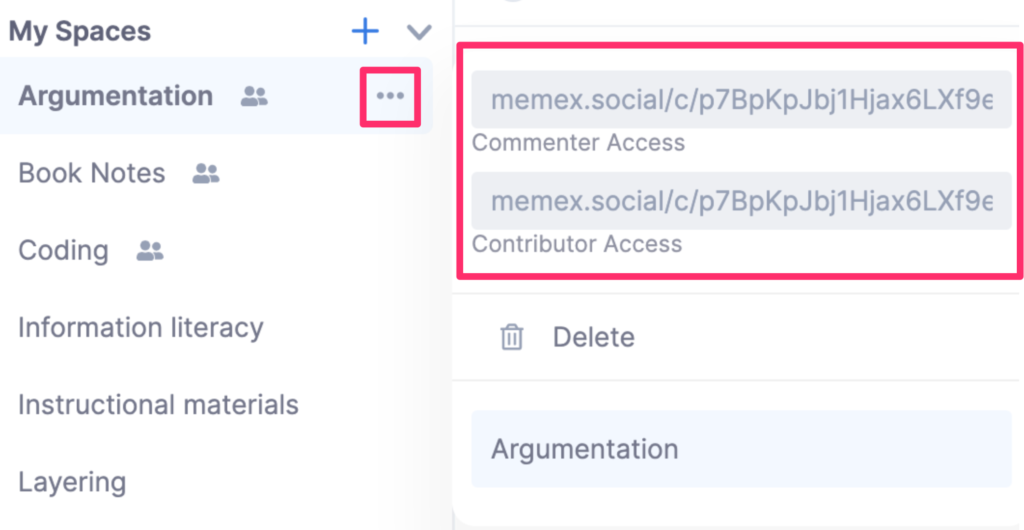

The notes from individual sources can be aggregated into Spaces. Think of a Space as a collection and this service’s alternative to a tag. A Space (collection) can be shared (see people icon in image indicating which Spaces have been declared public for sharing). When designating a Space for sharing the host differentiates whether those receiving the link to the Space can comment on existing resources or can have full access and add new resources.

Mem (and Mem X) are really more note storage platforms than bookmarking services. Mem includes a method for cutting and pasting content from other locations that is pretty handy (you don’t have to activate Mem when applying this technique so it transfers the “copied” content to the service automatically from other sources). I include Mem because it promotes the linkage of notes and it makes use of the AI suggestions to do this if you purchase the Mem X option.

The social component allows AI discovery of connections within “teams” or with identified colleagues. Mem makes a good example of the challenge of connecting. You don’t have to make use of the formal “TEAM” tier that Mem sells and which would make sense for organizations with groups working together. You can connect with other individuals, but how do you find them? This is the classic network problem new social platforms face. The platform can offer better opportunities than existing services, but the inferior existing service has existing connections among individuals that are more valuable than the capabilities of the service itself.

Mem X would be a great service if you had a way to bring a group to the service. A class of students or a series of classes taking the same course over a couple of years would be a perfect way to start a group with some common interests.

Mem is presently available at no cost so I still encourage those interested in note storage and the organization of stored notes (say an alternative to Obsidian) to investigate.

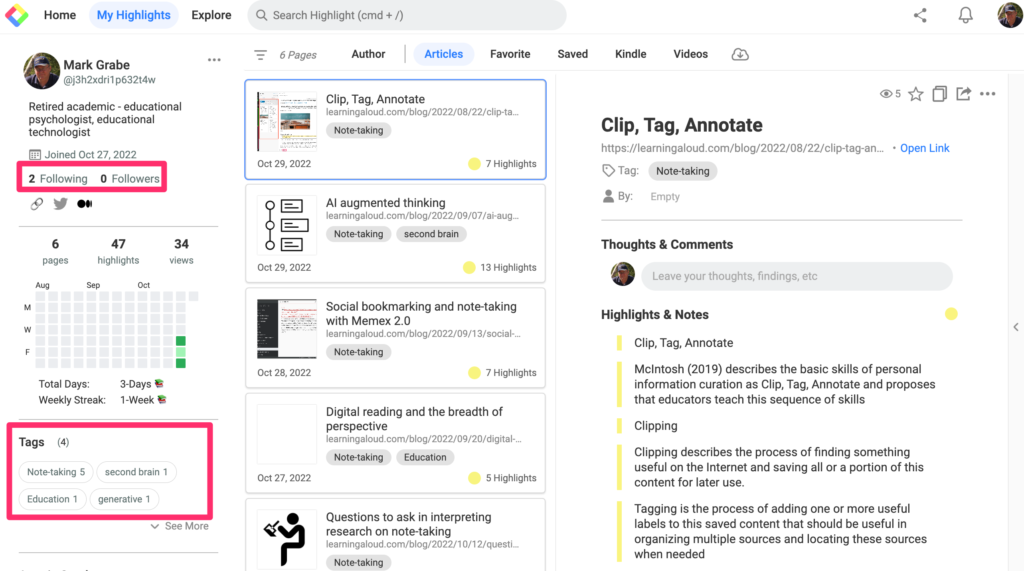

Glasp is a developing “social web highlighting (their description”) service. The focus on web content highlight and annotation makes the service more limited than some of the services I have included here. You highlight/annotate web content and add tags if you want. The features I like allows search of public content highlighted by others using tags. Tags can be used to find the public content stored by others and finding these resources allows you to find others to follow. There is no need (or requirement if you see this as a problem) in negotiating whether someone will be a collaborator so the issue of creating a personal social network is a lot easier.

Conclusion

I don’t see trying to rely on just one of these options. I pay for three and this would be unnecessary except I want to explore a couple of these services as they develop. If all are new to you, you should be able to try the free/trial options to see what you think.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.