A little background on this post. I have never been a strong advocate for educational games. It is difficult for me to separate my personal from my professional reaction to these games. I am not a game player. I am that family member who will not participate in family board or card games. In analyzing my own behavior, there are some forms of competition I find enjoyable (sports) and there are other forms of experience involving competition that I just find irritating. Professionally as an educator, I find learning from games inefficient and when I want to learn something I would prefer a more direct approach.

I do try to understand the interest others find in games and often engage with advocates regarding their support (this may be my competitive side). Usually, these folks agree with my position on learning efficiency, but have some other reason they think games are useful. Perhaps in response to a request for examples of games they would recommend, some resources from iCivics were provided. I have been exploring some of the iCivics resources which include games among what the organization provides. My experience has not changed my mind about efficiency, but I do see the content within the games. The example I suggest here – Argument Wars – happens to hit two topics that interest me professionally (classroom games and argumentation skills) and represents a combination of what I would describe as a simulation and a game. Argument Wars would make a good case for the educators I work with to analyze as either a game or a simulation.

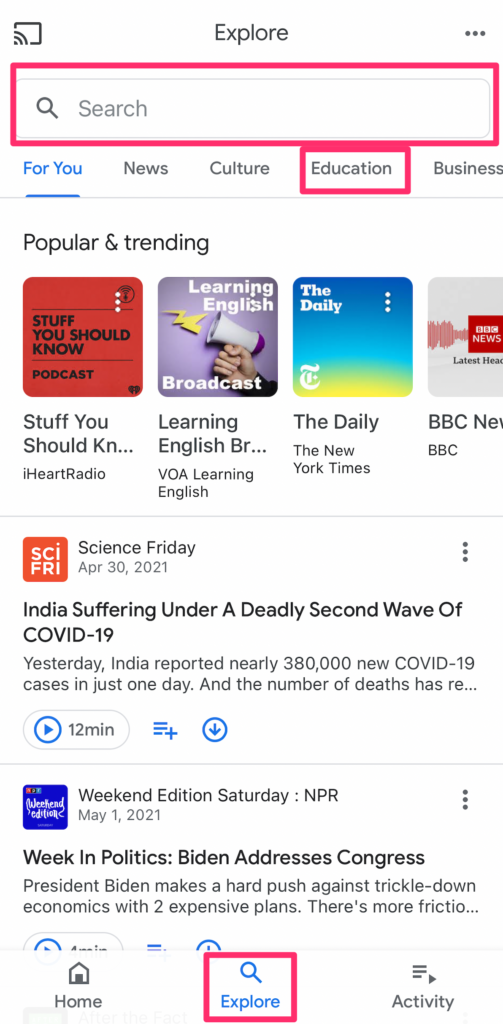

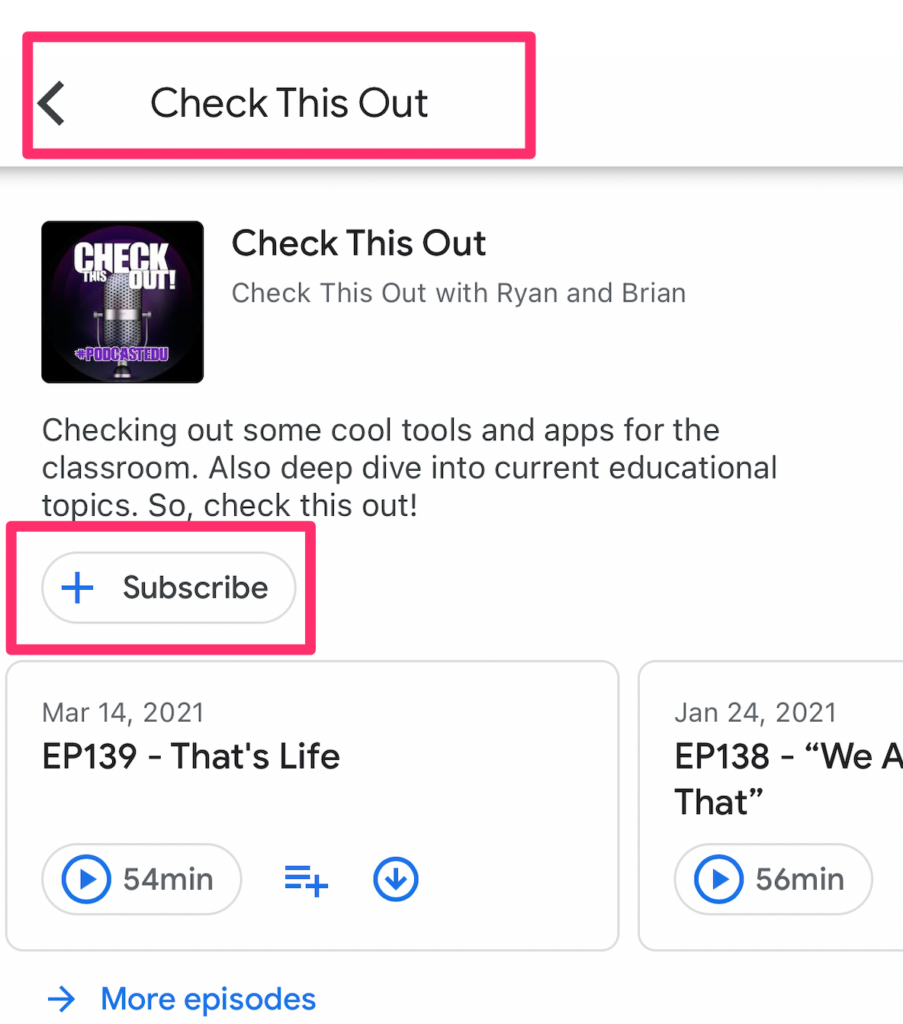

You can explore many of the iCivics resources at no cost. I would encourage you to play this game (simulation) yourself as a way to experience such activities and see what you think. The game (web-based or available as an app) will guide you through the experience and you can play against the machine or with an opponent. This would probably not be what I would recommend for classroom use, but it is a reasonable way to experience the activity.

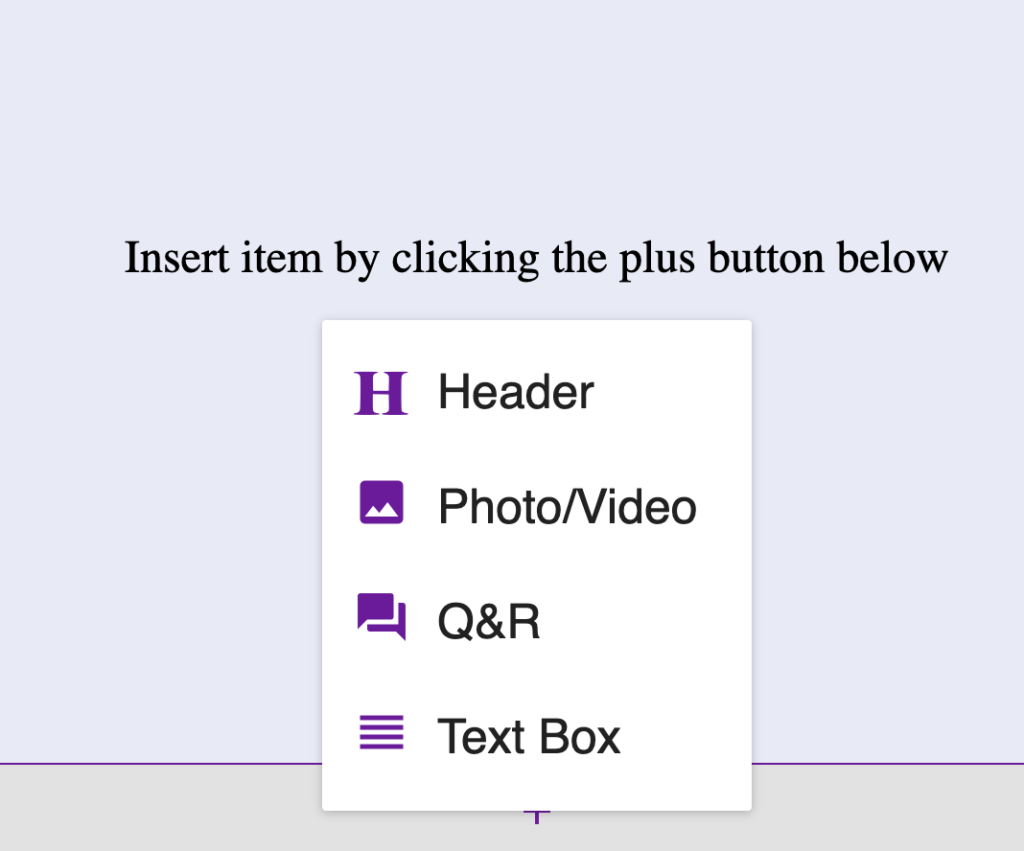

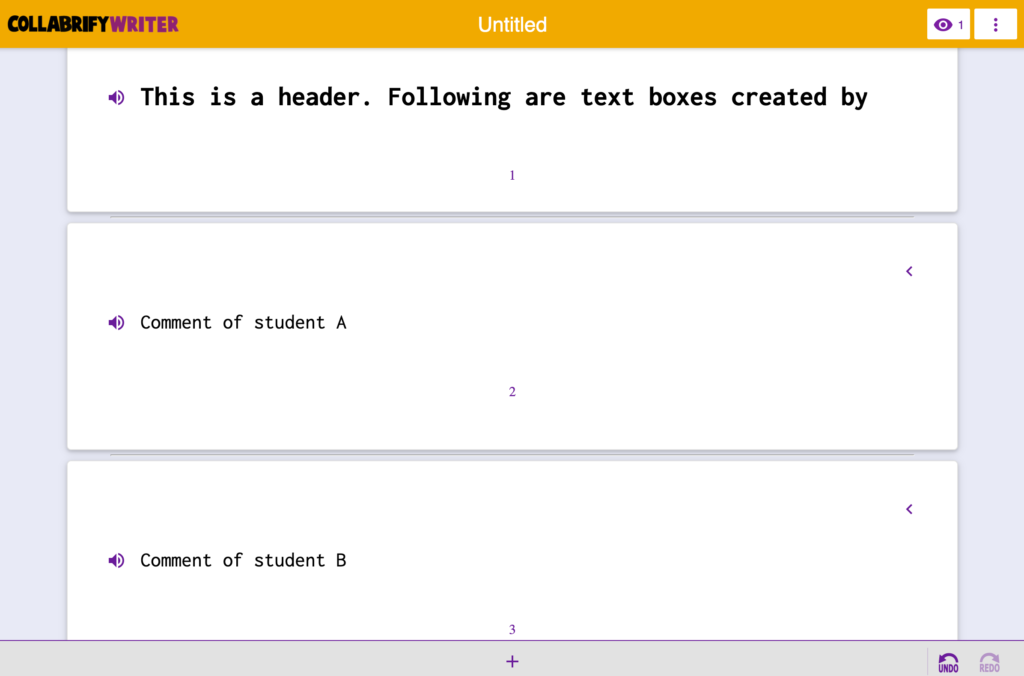

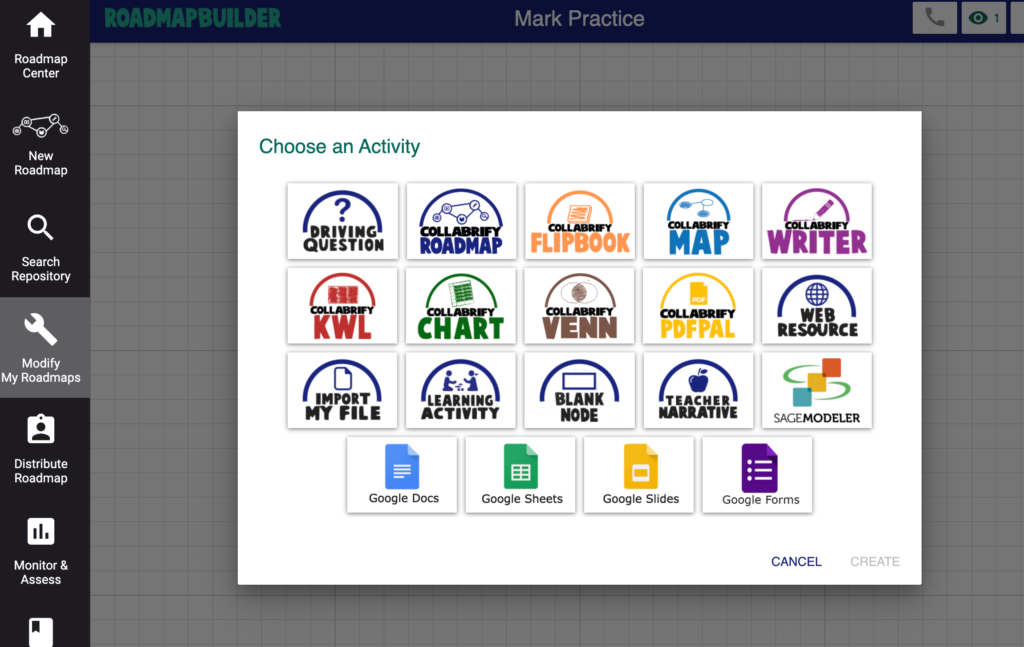

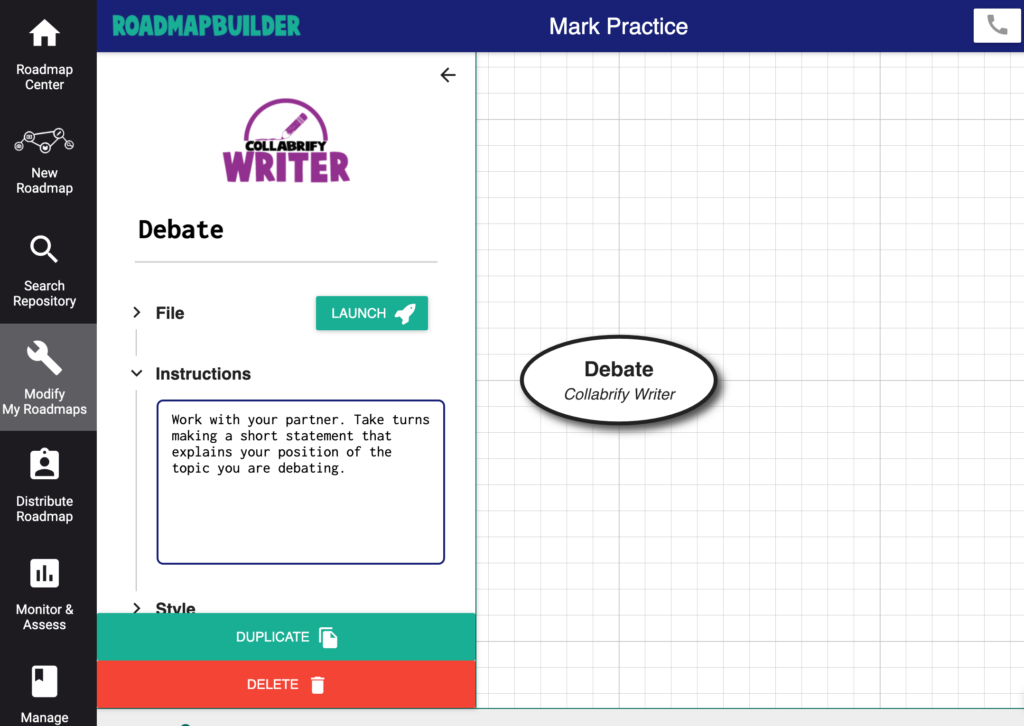

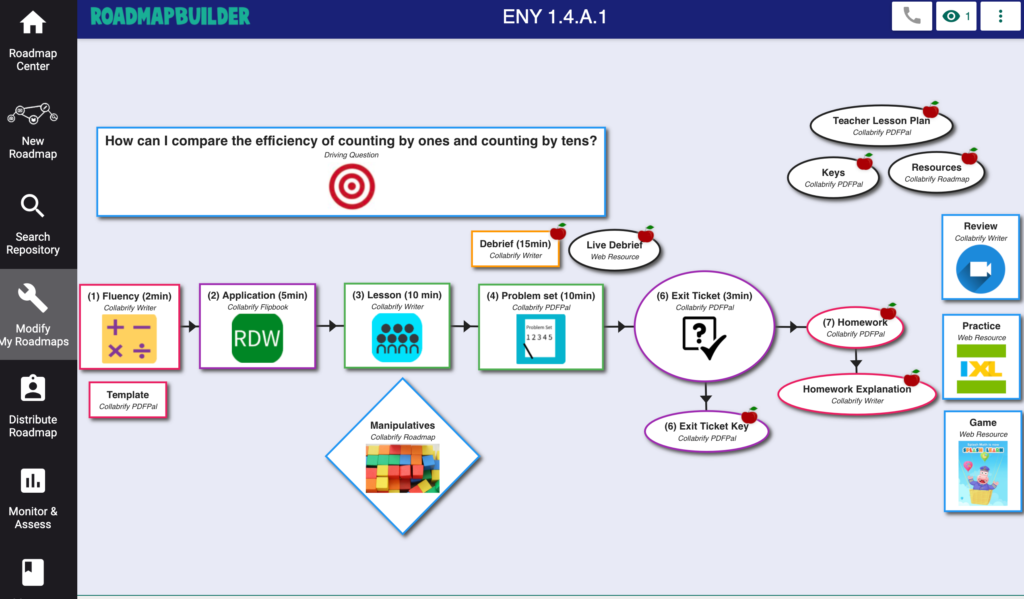

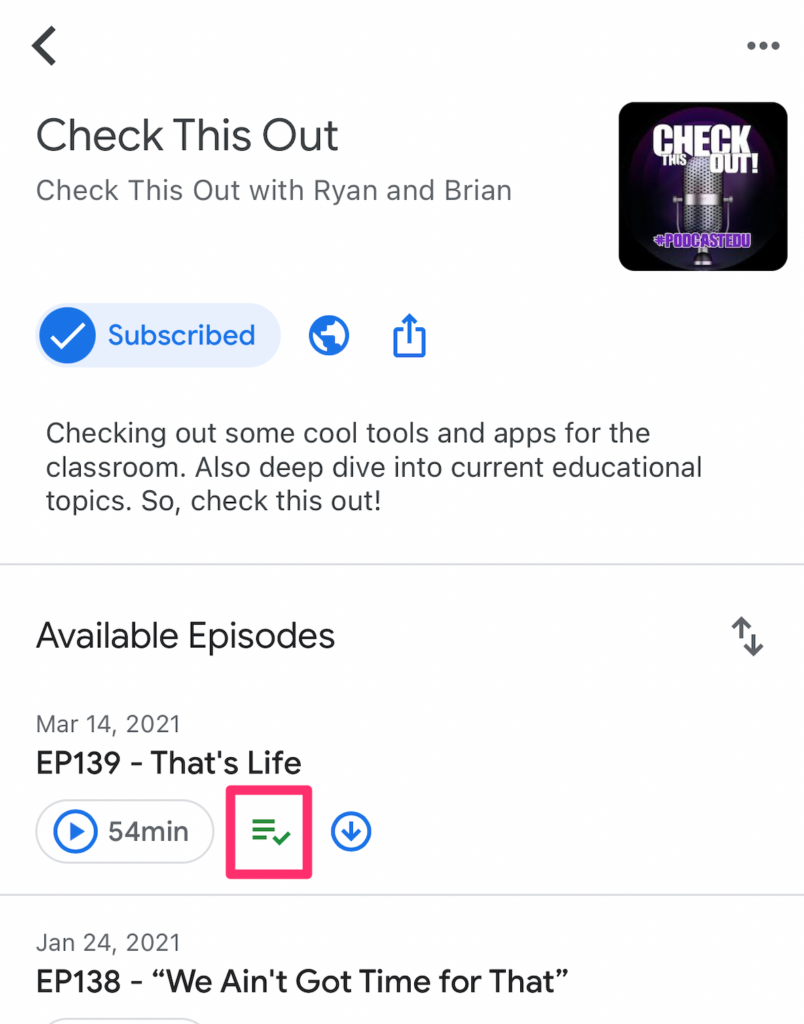

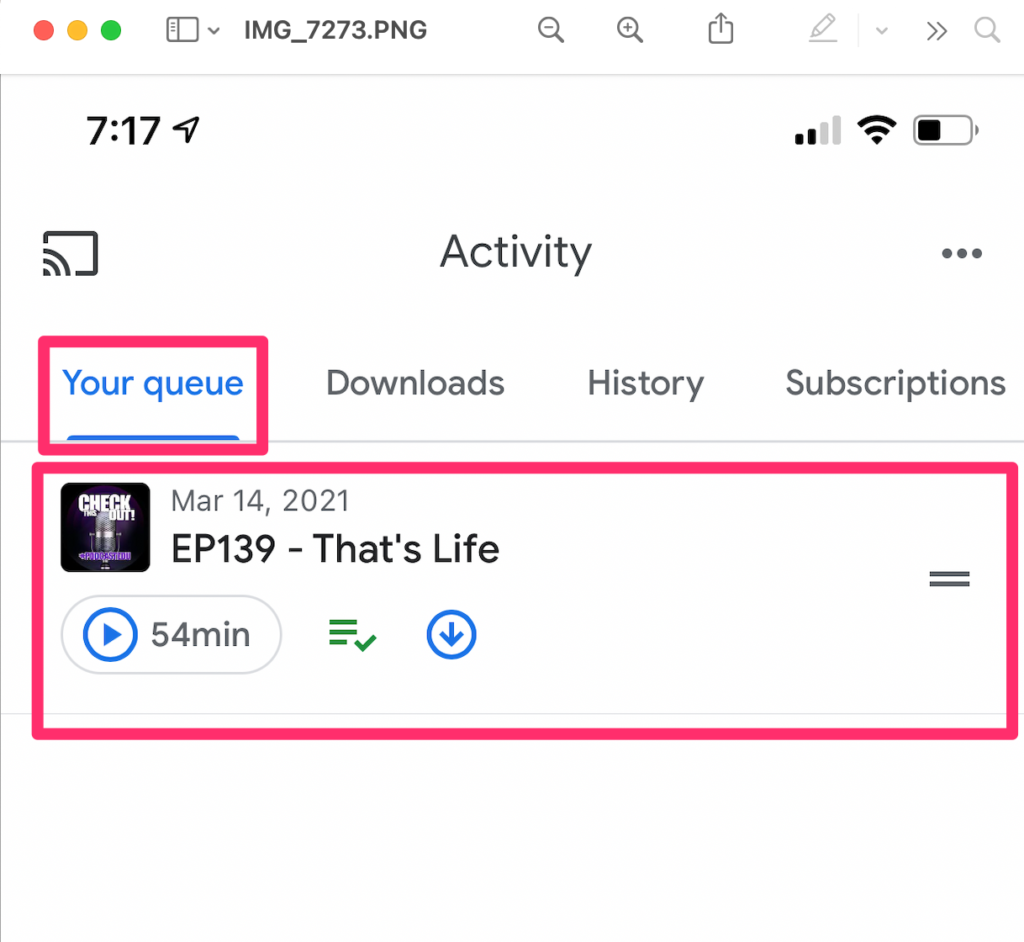

Here are few images to give you the flavor of the game. As I have already explained, the game will guide you so you give it a try without having to read a tutorial.

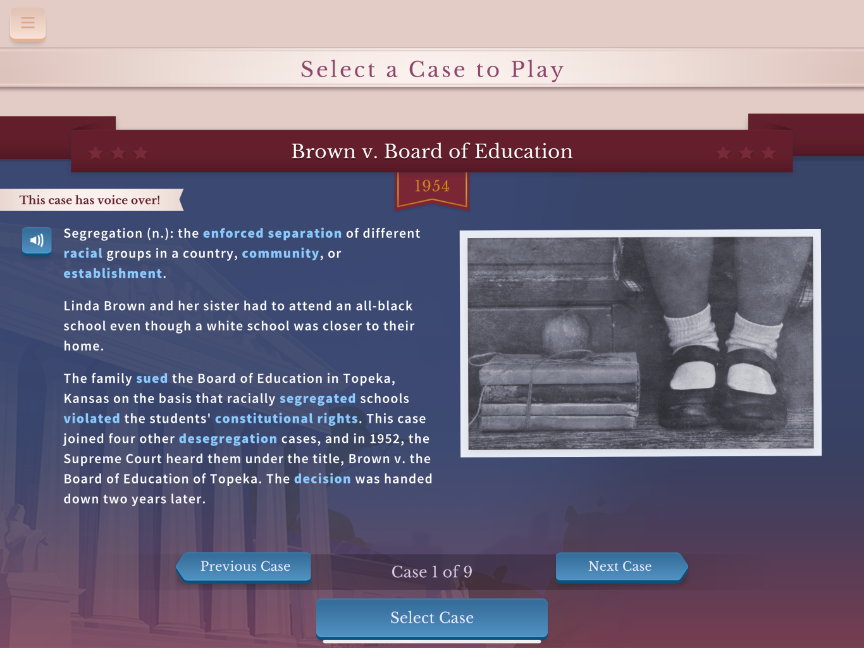

Argument wars examines key cases considered by the Supreme Court. Most educators are probably familiar with Brown v. Board of Education so selecting this game would be an interesting way to familiarize yourself with the activity. In the image below, you will see some of the embedded content explaining the case.

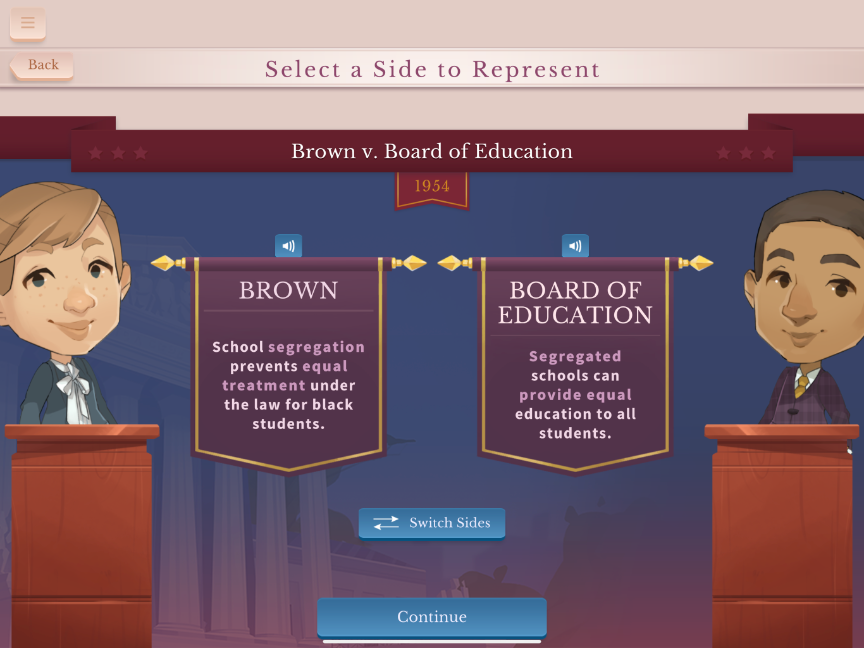

Again, you can argue either side of the case and for those interested in the process of argumentation it probably makes sense to try arguing both positions. You select an avatar and in the following image you are asked to select the side you want to take.

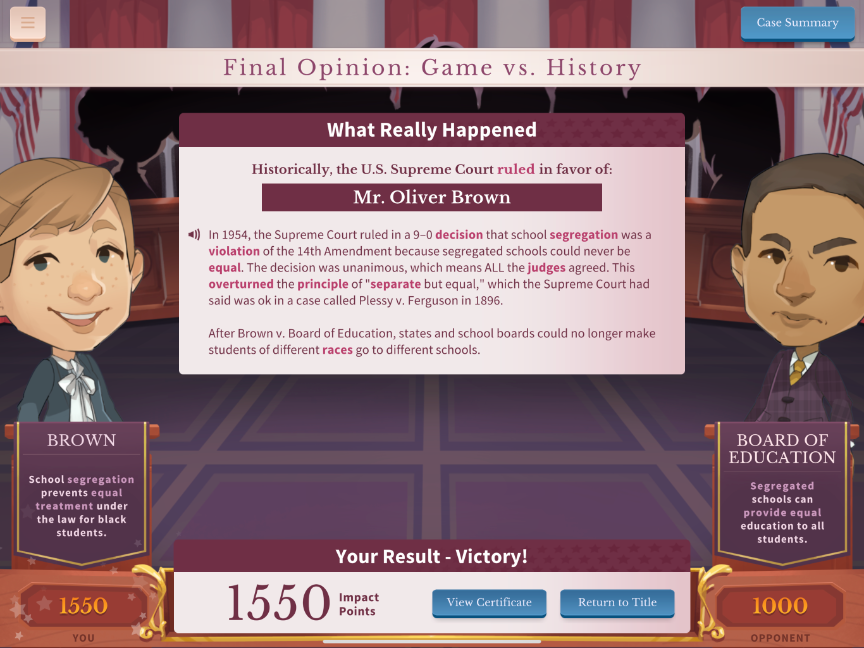

This image shows the basis for the game play. You are dealt three argument cards. You then fill out your hand by selecting two more cards – more arguments, strategies, or actions. You make an argument, attempt to refute a position taken by your opponent, remove a weak argument if you are down to only one and know you need a more substantial position, and more. The actions you can take are based on the action cards you have available so you must do the best you can with the arguments and the actions you have available. You earn points based on how the court judges the strength of your decisions. There are four rounds to the competition.

After four rounds, a winner is declared. The game/simulation then explains the outcome of the actual trial.

iCivics was founded by Judge Sandra Day O’Connor in 2009 based on her concern that citizens lacked sufficient understanding of how democracy works. iCivics offers various games among other resources devoted to this goal. [ description from Digital History]

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.