Cindy and I have a professional relationship that allows us to develop K-12 classroom ideas for technology integration. We approach our goals through a collaboration that allows each of us to take different approaches. This works well as long as the approaches are complimentary. Back in the day when “cooperative learning” was an “in thing”, this was called a jigsaw model. I have provided a link in case this trend had its day before your time. Cindy learns by doing and I learn by thinking (sometimes out loud). This means I do most of the writing.

Here is a recent exploration into the potential of “mini programmable robots”. We picked up an Ozobot at a recent conference and have spent just enough time with it since to understand some of the basics. An Ozobot is small – about the size of golf ball. It can be programmed in several different ways. One approach feeds instructions to the mobile bot through color codes imposed on the line that it is following. Different color patches on the line tell it to speed up, slow down, etc. Now the demos for this are suited to the size of the Ozobot – i.e., small. It might be asked to follow a pattern on the surface of an iPad.

What if instead of duplicating the typical small scale projects the company offers as examples you decide to apply a few basic principles to a project of your own design. What if instead of the surface of an iPad or a sheet of paper, you decide to build a lego city in your basement and allow the Ozobot to explore the city.

Cindy had a collaborator in this project. Some of our grandchildren were visiting and Preston likes “science” and legos. It turns out the kids think on a different scale than rational adults. None of this start small and then build up kind of thing.

I must say I would have started with the robot and figured it out first, but Preston wanted to build the city first.

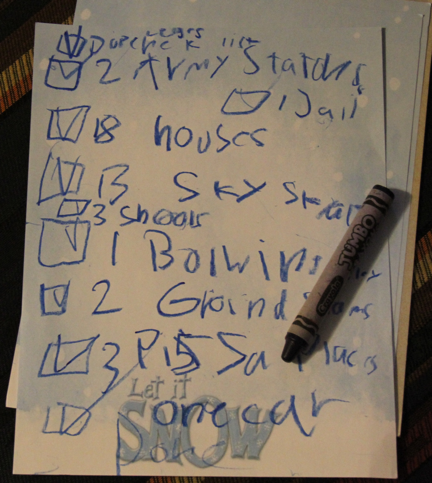

There was a plan (if you can read it). The plan specifies the structures to be included in the lego city.

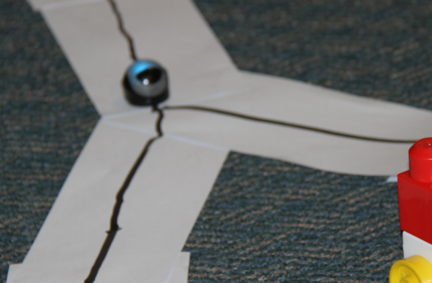

Now, it was time to construct the road (track). The idea was to cut sheets of paper in half and then tape them together.

Here is the closest thing to a test of concept. You can see the sheet to the left that explains the different color codes. We did learn that the width of the line is important. If the line is too narrow, the bot just stops.

Here you see the robot on part of the road. One unanticipated problem concerned the method for joining the paper strips. When taping the pieces together, one sheet must overlap the other. It turns out it takes very little to stop the small robot. If it runs into the end of the next strip it stalls. This is not an issue as long as the direction of travel moves from the overlapping piece of track to the underlapping (is this a word) piece of track. Now if the track moves in a circle you soon figure this out and all would be well. However, if you decide to have the robot come to a turn in the road (and take the path less traveled) the problem of having all of the road moving in a predictable direction became an issue. The finished product contained several “bugs”, but like some software I have used it worked most of the time.

My mom had this expression she applied to me when I was allowed to dish up my own food when kids were allowed to make such decisions at a pot luck or some other event. She would say – “see, your eyes are bigger than your stomach”. I wish this was still the case. Anyway, this project was far larger than it should have been for a learner of Preston’s age. We spent hours and hours over two days taping slips of paper together and then retaping sections when we understood that adjoining pieces of paper had to be connected in a certain way or when little sister walked through the lego village dragging her feet and messing up the road. Once constructed, there was probably far less interest in exploring and debugging than probably would have been the case should the adults involved have excercised more control over the scope of the project.

One of the issues I think is important when it comes to project based learning is the efficiency of the project. When should an educator “scaffold” a project to increase efficiency? How much independence should learners be given and what are the benefits and costs of frustration and failure? These seem to be current educational issues and I could see these issues play out as I spent several hours cutting 3 inch sections of tape for the workers to use in the construction process.

![]()