Kialo’s mission statement is to “empower reason” in the midst of a social media environment that seems to have lost the capacity to enable meaningful discussion. I see a great opportunity for educators here while Kialo has a broader focus. In a way, Kialo is similar to Hypothes.is, a service which wanted participants to “annotate the web”, both expressing a desire to develop services providing a way for all to participate in addressing important issues.

I am interested in the potential of Kialo because I have written about argumentation (similar to debate) as an important learning activity. My perspective has been strongly influenced by the work of Deana Kuhn who writes about the limitations of the perspective students often take in considering controversial topics and the value of teaching argumentation as a way to address these limitations and to develop critical thinking skills.

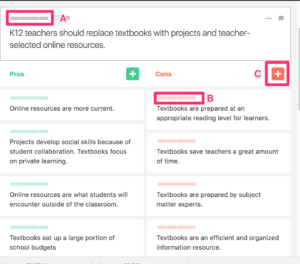

Kialo allows a host to state a thesis (e.g., Educators should abandon traditional textbooks and use projects and online resources), seed a discussion with several pro and con statements, and then invite others to react.

The “discussion” can be made public or shared with designated others (considered private). Invited participants can rate their level of agreement with the original premise (A), rate their agreement with specific pro or con statements (B), or add their own pro or con statements (C). They can also add their pro or con statements in reaction to existing pro or con statements. Comments and links can be attached to pro or con statements as a way of adding supporting evidence.

My thinking was that this service offers a way to implement some of the techniques suggested by Kuhn. Dr. Kuhn liked to use a simple messaging technique allowing participants to post brief arguments and evidence to each other. The value in this approach in contrast to a traditional verbal debate was the concrete record of comments allowing for followup and analysis. Kialo would allow this and has far more detailed opportunities for analysis should users want more.

Should you want to explore, I have posted the “abandon textbook” Kialo project and you are invited to participate.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.