An Example of Learning From A Simulation: “Sniffy - The Virtual Rat”

Here is an example of a simulation used at the college level. Allow us to introduce you to “Sniffy” the virtual rat. Sniffy lives in the virtual world of a “Skinner Box.” The Skinner box is named for the famous psychologist B.F. Skinner who discovered basic principles of operant conditioning by placing animals in carefully controlled environments in order to evaluate the influence of reward and punishment. If you are already familiar with Sniffy, it is probably because of experiences in an introductory psychology class.

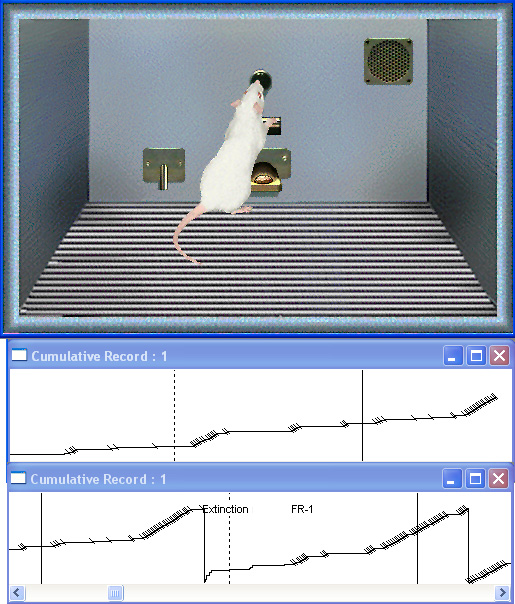

Sniffy: Sniffy in Skinner Box with displays from cumulative recorder

Sniffy has been programmed to exhibit the behaviors of a typical rat. He (or she) moves around the cage, sniffs at objects, consumes available food and water, reacts to sounds and light, rears on its hind legs, scratches, and exhibits about 30 typical rat behaviors. Watching Sniffy, it is easy to assume that this organism is somehow in control of its own behavior.

The programmers have accomplished much more than creating a convincing visual representation of an actual rat. Sniffy has been programmed to act based on fundamental rules of operant and classical conditioning. In other words, Sniffy can simulate some basic forms of learning and a human “researcher” can test his or her understanding of basic learning principles by attempting to train (teach) Sniffy.

It is easy to memorize the definitions of terms like reinforcement, punishment, and shaping, but it is a different matter to test your understanding of these concepts through application. With Sniffy or a live rat placed in a Skinner box, the first task is typically to teach the animal to press the bar to get food. It is a very simple action, but the rat is unlikely to acquire this response without assistance. Books and lectures typically suggest that new behaviors are most quickly acquired by reinforcing successive approximations to the desired behavior (shaping) and through continuous reinforcement. So, if you are now staring at your rat wandering about the Skinner box, what do shaping and continuous reinforcement mean? Shaping might imply that the rat should first be reinforced when it happens to move near the bar and food dispenser. Continuous reinforcement would suggest that in the early stages of learning a behavior, the reinforcer should be delivered every time the rat wanders near the bar. Once the rat learns to associate the area near the bar and feeding station with food, it becomes necessary to identify another approximation to the final desired behavior. Watching the rat, it becomes apparent that from time to time the animal rears up on its hind legs. It does not appear to do this to touch objects because it will produce this behavior in the middle of the cage, but the odds of striking the bar would be greatly improved if the animal could be encouraged to rear up near the bar. So, the next stage of training might result in the delivery of reinforcement if the rat is near the bar and rears up. Increasing the frequency with which the animal rears up near the bar will result in some contacts with the bar and the rat generating reinforcement for itself. As self-generated reinforcement increases in frequency, there is no longer a need to provide reinforcement for anything but the desired behavior.

If you examine the figure that appears above, you will note what are called cumulative recordings. This is a format in which those studying operant conditioning often display their data. The recording moves along at a constant rate and each response by the rat results in a vertical increment in the line. In the top recording, you can view what might be described as the end of the training phase. The animal has begun to respond at an accelerating rate. Once Sniffy has learned to press the bar to obtain food, this response should be maintained by its own consequence. At this point, other operant conditioning concepts can be tested. Extinction is the reduction in the frequency of a learned behavior that no longer generates consequences. The software controlling the Skinner Box allows the delivery of food to be turned off. When this is done, a bar press no longer results in access to food. The bottom cumulative recording demonstrates what happens when Sniffy no longer receives food for bar pressing (see the point associated with the extinction label). It appears that several bar presses occur in quick succession and then the rate of responding quickly diminishes. When food is again made available, the occasional bar pressing behavior of the rat is again rewarded and responding quickly picks up. This quick return of an established behavior after a delay is called “spontaneous recovery.”

“Sniffy The Virtual Rat” is example of what we describe in the Primer as a simulation. The simulation functions according to a set of underlying rules or principles and the intent is that by interaction with the simulation the learner will acquire and understand these underlying rules or principles. Educators considering this or other simulations might ask several important questions. Why bother to take the time to provide a “hands-on” experience of any kind - why not just present or have students read about key concepts? If manipulative experiences are important, will working with a computer program serve as an adequate substitute for or be superior to experiences with the real thing? How do cost, efficiency, and learning outcomes compare? The Primer describes some of the theoretical arguments for the use of simulations and a section available online offers a summary of recent research on all categories of instructional software.