Combining GPS and GIS to Explore Local History

The connection of many types of information to location can provide a context that helps us gain a deeper understanding of that information. We either have existing knowledge that the identification of locations can activate or we can use identified locations as a starting point for learning something new. By mapping multiple sources of information to locations we may even discover relationships that were not originally obvious. It can be helpful to ask the question, “Why did that happen here?”

The use of location data to provide context can be applied in a wide variety of content areas. We encourage you to generate your own examples related to your personal interests, but here are some sample questions we propose just to spur your thinking:

1. What locations provided the settings for the books written by Laura Ingalls Wilder?

2. What was the route of the Lewis and Clark Journey of Discovery and what locations marked significant events along the way?

3. How did the distribution of red and blue states change between the elections of 2004 and 2008?

4. Which parts of the state are more heavily populated by white tailed deer and which by mule deer?

Put aside your own location and content interests for a little while and consider the following example. If you asked your students to research similar questions, how might you then ask them to represent their findings? We remember being given paper maps of various types and being asked to add information to the maps. When maps are used by students, this is still a common method. So, the questions we list might be addressed by locating relevant information in various ways, adding notations or markers to a paper map, and perhaps writing a short paper to offer details and an explanation of the annotations to the map. Access to digital maps and related multimedia tools offer new ways to engage in similar projects in ways we think are more authentic and interesting. Here, we provide a description of one tool as the tool might be used to implement an educational project.

Project: Using Scribble Maps to Explore and Share Historically Significant Sites In Your Community

Scribble Maps is an online service that provides a relatively simple way to overlay markers, shapes, lines, drawings, and images on Google maps. There are far more powerful GIS applications used in school environments and there are also other entry level applications, but the basic level of Scribble Maps (there is a pro level) makes a good example we might convince you to explore. Like many of the examples we use, the basic level of Scribble Maps is free and can be used from within a web browser. There are some exceptions because the site makes use of Flash, but the company responsible for this service promises there will be work arounds for devices such as the iPad.

The example that follows makes use of some specific Scribble Map features. We wanted to be able to locate specific buildings either by searching Google maps for street locations or GPS coordinates, to mark these locations in a way that would allow the attachment of basic descriptive information and links to external Internet sites (specific images taken of locations stored online), and to provide access to the finished map to others as an Internet address. The concept here is that a group, e.g., a class, might generate such a map as a project and share the product with others. This is a simple approach that ignores such possibilities as multiple groups at multiple locations contributing to a common map, but a collaborative effort would certainly be practical and would require only that those participating groups share a password. The topic providing the focus of this project concerned local historic sites presently listed by the National Register of Historic Places. Approximately 60 sites in the county in which we live, most in our community, are presently listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Many of these buildings are familiar to students and ourselves, but not as historic locations. We are more likely to know such buildings as the places we visit for some of the better pizza in town, the retirement community in which grandma or grandpa lives, or the office of a lawyer to assist us with our taxes. Who knew we had an impressive opera house that still stands? The listing of Historic Places is maintained by the United States Department of the Interior and we were able to locate a wikipedia listing of the sites presently included in our county. This site included street addresses and GPS coordinates as well as external links to “nomination documents” maintained by the Department of the Interior. The nomination documents are available online for review and these documents offer a unique opportunity for anyone to explore primary sources (see the summary of the building of Washington School which we provide a little later in this project description - Supplementary Listing Record for Washington School - forms prepared by Roberts, N.).

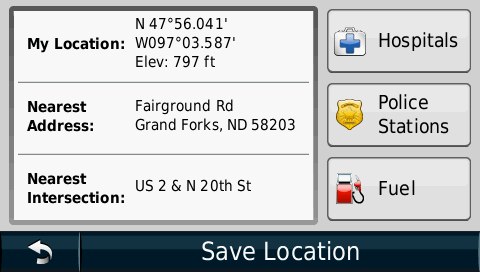

The first task was to locate the historic sites in order to take a picture of the building as it looks today. This could have been accomplished using either the street addresses or the GPS coordinates identified in the list of sites. A unique feature of the GPS device that was available provided an interesting opportunity. The device, a Garmin Nuvo, can store a digital copy of its own screen. Such images, typically called screen shots, are stored in the GPS and can then be exported. The strategy was to locate the desired building using the street address, walk to the front of the building with the GPS, use the “Where am I?” feature to generate GPS coordinates, and capture these data using screen capture (see image). The coordinates could then be entered into Scribble Maps to determine whether the appropriate building was identified as well as compared with the coordinates provided as part of the Register list. There are lessons to be learned when exploring with authentic tools and data. The process is not error free.

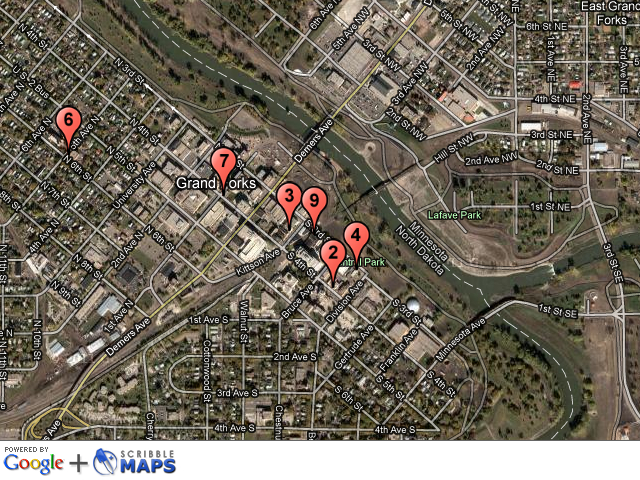

Once the appropriate building was identified in Scribble Maps the location was marked with a “place marker”. Place markers have the appearance of stick pins on the maps, but each can be annotated with a title and description. When a visitor to the finished online product selects a specific marker, the title and description are revealed. The description field allows the inclusion of web links. Rather than enter a significant amount of text in the description field, a web link was inserted that connected to the image taken of that building stored on Flickr (an online photo storage and sharing site we will describe in another chapter). In some cases, additional information was stored with the image on the Flickr site.

Scribble Maps is very versatile and various products can be created. For example, content can be exported as a KML file (keyhole markup language) which can then be loaded into other “mapping” or GIS tools (e.g., Google Earth). You can export a simple jpg image of the map you have created (Note - this is the way we generated the image that appears here). Finally, you can share the map, annotations and markers as a web site for others to explore (e.g., http://www.scribblemaps.com/maps/view/gfsites2011). It is this final option we imagine as the most likely product of a class project. Consider again our earlier arguments that students learn through the processes of authoring and teaching. What we have described is a unique format in which to express what has been learned.

The Story of Washington School

What might be the context in which the specific example described here might be used? Students in North Dakota are required to study the geography, history, government, and current issues specific to their state in 4th grade, 8th grade and in high school. You may have experienced something similar to “North Dakota Studies” in earlier phases of your own education. Imagine the opportunities for the type of local explorations we describe here, perhaps as a collaborative activity with others in your region, that might be used to augment the more traditional activities in such courses.

There turned out to be plenty of opportunity for practicing “historical inquiry” in this project. In fact, you might think you would have little interest in some old buildings in a community you have never visited, but you might be surprised. People often share commonalities of many types and if you are reading this material you are likely to share an interest in education. A couple of buildings listed in the Register were originally built as schools. The document associated with the building of Washington School (Pin #6) describe a situation all to familiar to many present educators who have been through a local process of building a new school or other new facility costing an significant amount of money. According to the documents filed when Washington School was proposed for the National Register, the decision to build Washington School was made during what was described as the “Second Dakota Boom” of 1895 to 1917. Evidently, during the years of 1900 to 1910, the population of Grand Forks, North Dakota, increased from 7,652 to 12,478 placing great pressure on the capacity of local school facilities. The year of 1906 alone saw an increase of more than 300 students. Despite this significant growth and the crowded conditions in the existing facilities the school board was reluctant to invest in a new building. There were battles over cost and location. Do we really need to spend this much money? Where within the expanding community should the new school be located?

Minutes from the school board meetings summarized in the filing document describe the year-long political struggle. The minutes tell the story of school board members reluctant to spend money on new buildings, changes in board membership, battles over the location for new construction and an eventual compromise, and the eventual downsizing of the original building plans in order to get the project approved. There are plenty of interesting details revealed through careful reading. Students in Grand Forks would recognize the names of school board members mentioned in the minutes - several present schools are named for these individuals. These students may not appreciate some of the financial details without some guidance. For example, even though the alterations to the original design were likely considered significant at the time, the budget adjustment necessary to secure enough votes to begin construction was less than $10,000.

The present building that was originally the Washington School

(Sperry, J. (1991). National Register of Historic Places Registration From (for Washington School, Grand Forks, ND). Available online - http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NRHP/Text/92000035.pdf )