Changing Preferences for How We Learn

They are not like us

Some are willing to take the position that the children in today's K12 (and perhaps college) classrooms are qualitatively different than students of previous generations. By qualitatively different, I mean that the differences are not a matter of knowing a little more or less or being a little more or less advanced in the development of certain thinking skills, but rather that individuals process information taken from the environment surrounding them in different ways.

One prominent writer taking this position is Marc Prensky (2001, 2006). I believe that his perspective has become popularized because of the analogy he uses to describe the changes he believes have occurred. You may be familiar with his terminology. Prensky differentiates those who have grown up with digital technologies from those who have learned (or not) to use these same technologies as ''digital natives'' and ''digital immigrants''. In keeping with this reference to geographic and cultural change, he describes those of us who have developed whatever skills and knowledge we have later in life as having an ''accent''. To adapt, immigrants are best served by taking their lead from the natives.

The argument goes further, Prensky tentatively connects the typically age-based distinction he proposes with advances being made in the field of neuroscience proposing that preferences for learning experiences and what I would describe as cognitive capabilities have a biological basis generated by years of intense experience.

What are some of the core differences in experience? Natives have thousands of hours functioning in environments in which they:

- receive information in multiple formats especially visual information,

- receive multiple streams of information on different topics, and

- interact/respond to information.

The concern is that ''in education'':

- the manner in which information is presented,

- and the manner in which the skills expected in "processing" this raw information are expected to be practiced may not be aligned with fundamental changes that have occurred.

The consequences of this misalignment may include boredom, frustration, and shallow learning (retention without understanding).

These are dire claims, but in some ways similar to comments that older educators have always made about younger students. Even if nothing fundamental has changed, perhaps it is worth considering whether activities that more actively involve learners can result in motivational advantages.

Prensky's passion is video games and he argues that games are suited to the learning style of digital natives.

Let us suggest that the speculation about:

- a fundamental generational difference in learning styles,

- a biological basis for such generational differences, and

- games as model for learning

should still be regarded as interesting hypotheses.

It also seems reasonable that what exists as differences may reflect differences in frequency of life experience and peer pressure and represent preferences rather than biological differences. Such differences in preference may be suited to a variety of learning environments one of which may be games. In fact, the participatory web may offer a practical and immediate way to recognize these learning preferences.

At this point, you may be reacting to some of these statements by assuming that you are a victim of this lag. Your instructors are from a previous generation and do not appreciate your life experiences or how your generation learns. Perhaps so. However, as you prepare to operate in the classrooms of the future recognize that you too are already significantly different than those you will teach.

This our granddaughter Addie. Before the age of 2 she would ask mom to talk to her grandparents on the computer. Whatever your present experience with technology, I am guessing most of you have less experience with point to point video than she does. And, if you think about claims made by Prensky, she is different from you because she has no experience with a different way of life. You have learned or could learn to use point to point online video, but you are already an immigrant in her technology world. Interacting in real time with people using a computer is simply the way her world works.

to her grandparents on the computer. Whatever your present experience with technology, I am guessing most of you have less experience with point to point video than she does. And, if you think about claims made by Prensky, she is different from you because she has no experience with a different way of life. You have learned or could learn to use point to point online video, but you are already an immigrant in her technology world. Interacting in real time with people using a computer is simply the way her world works.

Thinking about such experiences has allowed me a less defensive way of considering some of these issues. It has become ironic to listen to expressions that present generations of students have a different and often unappreciated perspective on the world when I started to recognize that this new perspective I was being asked to appreciate was already outdated. Perhaps it is sufficient for all of us to recognize that the process of change is inevitable.

Research Relevant to These Claims

We often turn to surveys conducted by the Pew Internet and American Life Project when searching for data on patterns of technology use. The Pew Internet and American Life Project conducts a series of data collection efforts to track trends in Internet use. Typically, the studies are done by identifying and contacting a randomly selected national sample.

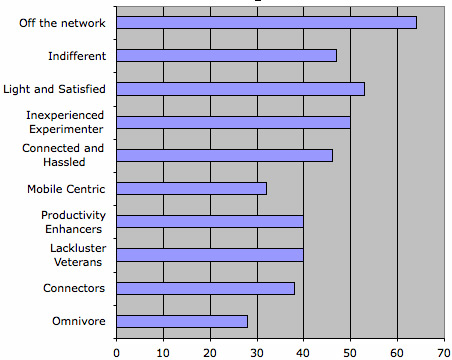

A 2007 survey of individuals over the age of 18 (Horrigan, 2007) attempted to generate typologies of technology use. This effort resulted in 9 categories of users. What is relevant to the present discussion is the '''median age''' associated with these categories (remember only participants over 18 were involved). Both attitude and centrality of technology in daily life were clearly related to age.

Another study released late in 2007 asked questions related to the use of social media. The questions guiding PEW data collection are typically not focused directly on educational issues, but because of the sampling procedure the data provide nice snapshots of how different populations use the Internet. The data referenced in this second study offer the strong suggestion that a high percentage of adolescents are already involved in creating online content. There is mention in the report of using social media (blogs, wikis, photo sharing, social networking) for educational tasks, but the questions were not asked in a way that allowed the isolation of data on the frequency of such activity. Our use of data from PEW studies is typically to make the point that many adolescents are engaged in the types of activities we advocate can be adapted to educational purposes.

The PEW data used here (Lenhart, Madden, Macgill & Smith, 2007) were collected in 2006. As active as PEW is in collecting data, the time lag in making public any data associated with Internet activity should always be noted. The report begins by noting that 93% of adolescents in the 12-17 age range contacted used the Internet and 64% of Internet users were involved in some form of content creation activity. Note - that the percentages associated with a given activity in the following comments is based on the sample using the Internet, but since this percentage is very high the numbers would be only a little smaller if applied to the entire population.

Here are some basic descriptive statistics:

- 39% shared artwork, photos or video,

- 33% had worked on blogs or web pages for others (this is the category in which school tasks was mentioned),

- 28% had their own blog,

- 27% had their own web page, and

- 55% had a profile on a social networking site.

To us, these values are surprising large (and have increased since the previous study conducted in 2004). Potentially, the numbers are somewhat inflated as a reflection of independent activities (e.g., sharing a photo would be a high probability activity for anyone with a social network profile). However, we offer these data as an indication that content creation is ongoing activity for many adolescents.

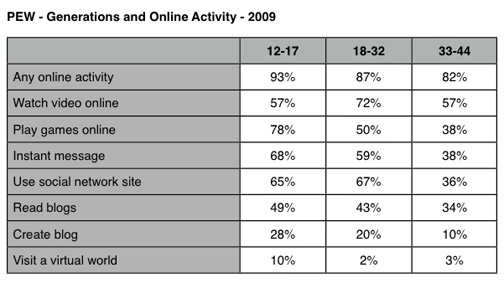

The most recent data from PEW for those areas in which teenagers are most different from other generations looks like this (Jones & Fox, 2009 - see Table).

Jones and Fox report that there are generational differences in Internet use. Teenagers (age 12-17) make most active use of the Internet and they are among the most active in many of the categories that might map to the tools/services that are the focus here.

The authors conclude that while there are generational differences in general use, it may be more productive to examine online behavior in terms of generational differences in priorities. They attempted to cluster different types of online activities and described the cluster of activities identified in this table as focused on communication and entertainment. Other generations may place greater emphasis on Internet activities less available or less interesting to teenagers (banking or health information). Perhaps of some relevance for educators - teenagers were not distinct in using the Internet as an source of information.

John B. Horrigan (2007). A Typology of Information and Communication Technology Users. PEW Internet and American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_ICT_Typology.pdf Access: July 23, 2007.

Jones, S. & Fox, S. (2009). Generations online in 2009. PEW Internet and American Life Project. http://www.pewinternet.org/PPF/r/275/report_display.asp

Lenhart, A., Madden, M., Macgill, A.R. & Smith, A. (2007). Teens and social media. http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Teens_Social_Media_Final.pdf

References

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital game-based learning. McGraw-Hill, 2001.

Prensky, M. (2006). Don't bother me mom - I'm learning. Minneapolis, MN: Paragon House.