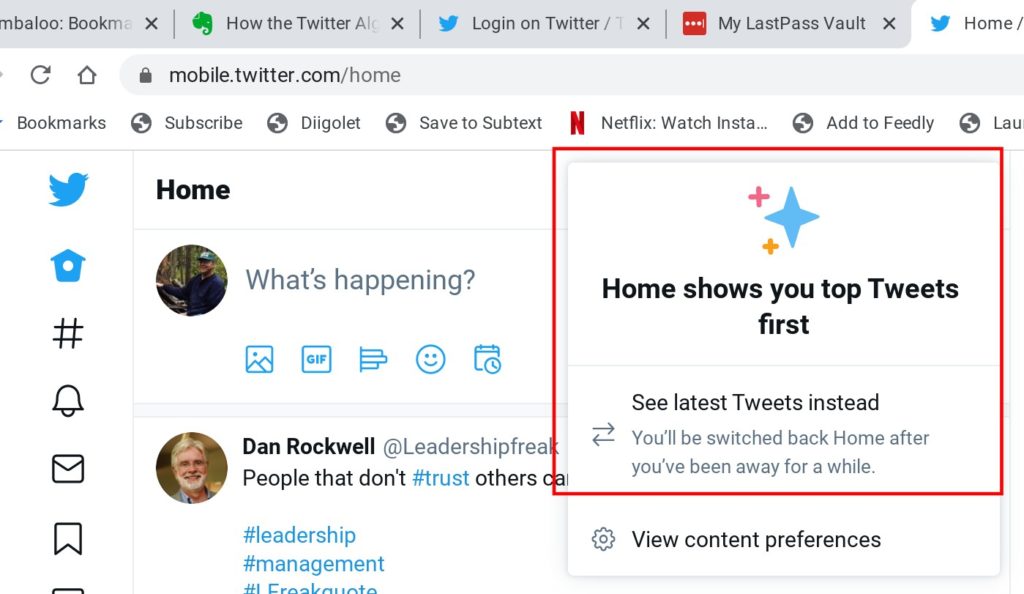

The events of the week have been troubling and raise serious questions about the effectiveness of our government and some of those in political offices. For me, an interesting side issue stemming from the complaints of politicians regarding actions taken by social media companies has been claims of violations of free speech. Such accusations first surfaced with Twitter attaching disclaimers to tweets from President Trump related to the election. Trump’s claims were visible, but followed by a comment such as “this claim is unsubstantiated”. Complaints only intensified when President Trump and others were banned from multiple social media platforms following statements claimed to incite the riot that saw the breaching of the U.S. Capitol by a mob.

Here is a way of thinking I often find useful. There is often an important distinction between terms as used in everyday speech and terms having an official meaning. Is free speech such a term? If so, do people complaining about a situation involving “free speech” and assuming a formal meaning (say a constitutional or other legal concept) confuse the formal meaning with some personal notion of freedom? I have been trying to figure this out.

Here are some thoughts on free speech and social media based on my review of a few sources. I provide links to a NYTime article and an analysis from the Congressional Research Service used as my sources.

While multiple precedents may bear on the issue, two, in particular, have received the most recent attention – the First Amendment to the Constitution and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

The freedoms described in the First Amendment are about freedoms “the government” cannot deny. The amendment does not concern itself with decisions made by businesses or organizations. In fact, when President Trump tried to block citizens from access to his Twitter account this was denied on legal challenge because it was decided he was using Twitter for a government function. Likewise, it can be argued that someone acting as a government representative trying to control what a media site distributes would be violating the media service’s freedom of speech. So, it would be Twitter or Facebook who could complain about the government attempting to challenge their right to free speech.

Section 230 argues that social media services are not publishers and hence are not libel for content posted by contributors AND allows these services to act “in good faith” to protect users from objectionable material contributors have attempted to post. It is this second protection that many seem not to notice.

I am guessing the First amendment is here to stay. Section 230 is likely to be challenged in the future as some argue that making decisions about content appropriateness and prioritizing the appearance of content based on algorithms amount to publishing. Section 230 is being questioned by both the left and right. Clearly, the protections afforded social media services have resulted in tremendous economic benefits. Social sites functioning at the size of YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook would find it difficult to quickly locate, interpret, and delete content meeting what are vague definitions of decency and danger. The Pew Research Center in 2018 found that 68% of U.S. adults use Facebook, 35% use Instagram, and 24% report using Twitter. That is just in this country. Understand that social media companies could be challenged both by those viewing things they did not like and by those having content they had worked on being taken down for what they might regard as trivial reasons. Others also argue that even though moderation would be a difficult challenge likely to result in suits no matter how much effort was expended, that it would be the larger companies most able to adjust or pay the legal costs of fighting complaints and smaller startups would simply be unable to take on such challenges.

So, free speech in a formal sense is not an appropriate way to understand the present situation. As far as what social media companies could do, there are other arguments to consider. At one point, I thought Zuckerberg was claiming that allowing the President and supporters to post unquestionably false information was in fact useful because it revealed something useful to the general public. Obviously, he has reversed this position because of the dangerous consequences we all have witnessed this past week.

Congressional Research Service – Free speech and the regulation of social media content.

NYTimes – Can Twitter legally bar Trump? The first amendment says yes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.