Introduction

Opening Comment

Let's begin with a basic claim and a related list of expectations.

What people are able to do because of access to the Internet has evolved dramatically and it is of such great importance that educators should:

- acknowledge these changes,

- prepare themselves and their students for challenges these changes impose, and

- take advantage of the educational opportunities these changes provide.

Some claim that collectively the changes constitute qualitatively different capabilities and much in the way advances in a software program are credited with a full numeral increment to recognize significant advances (Version 1.0 to Version 2.0) have applied the label Web 2.0 (O'Reilly).

The phrase ''participatory web'' is better suited to our purposes and still represents many of the advances associated with Web 2.0. We prefer "participatory web" because of the narrower focus on opportunities for anyone with reasonable access to interact and contribute. It is true that opportunities to interact (e.g., email) and contribute (e.g., web pages) have existed since nearly the beginning of "Internet time." However, as the participants have grown drastically in number, the tools have become more powerful, and our values and expectations have changed, the online experience can be very different.

Perhaps our comments to this point have been too vague and beginning with examples may be most productive. You may recognize some of "services" commonly mentioned as participatory web apps.

- flickr - photo storage, share, tag, describe, mashups

- facebook - social networking for students, multimedia authoring

- blogger.com - blog, comment, tag, multimedia

- iTunes podcasts audio/video authoring and sharing

- youtube - store video, share, view, tag, rate

- del.icio.us - social bookmarking (Internet favorate sites], share, tag, describe

- wikipedia - collaborative authoring and editing

We provide these examples because we assume you are aware of at least a few, not because we are proposing that the examples are suited to educational applications as the examples are commonly encountered or that a given example is the most educationally relevant within a category (e.g., all blog services, all wikis). We also are not proposing that we have identified the full range of participatory applications/services. What examples from this list may demonstrate simply by their survival and popularity is that Internet users seem to find the applications useful or at least entertaining. Our intent is to offer these examples as a frame of reference before attempting to identify ''characteristics'' of these or other examples that both explain what experts argue make such a collection of services different from what was available previously and perhaps set the stage for speculation regarding the adaptation of such services for educational purposes.

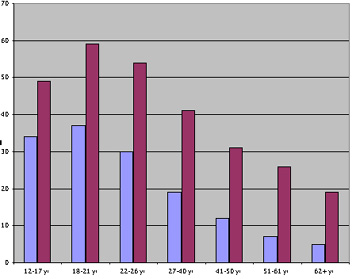

Participation is growing. Data from a 2007 issue of BusinessWeek, some of which is summarized in the image appearing below, shows age differences in production and consumption of typical categories of participatory content (web pages, blogs, video, podcasts). These data do not include social networking activity (MySpace] which also involve the production and consumption of content. The higher values are for consumption, but the level of production may surprise you. Of course, frequency of production is an important variable and these data do not really explain how often individuals participate.

Characteristics of the Participatory Web

The examples we list above share certain characteristics. Taking some time to consider these characteristics is productive because it is the characteristics rather than the examples that make the case for a qualitative difference in the way many use the Internet.

We take our list of characteristics primarily from a frequently cited essay on Web 2.0 authored by Tim O'Reilly and from a white paper describing online participatory culture written for the MacArthur Foundation by Henry Jenkins (note this is a pdf). We are not repeating all of the characteristics these authors identify and you are encouraged to read these and related papers (e.g., Searls).

O'Reilly (2005) notes a relative focus on the:

- participation of many

- opportunity to harness collective intelligence

- assumption of perpetual beta (resource changes and improves) and an increase in value as contributions/use accumulate

- value of service and data more so than the software.

- opportunity to access data at a specific (granular) level

- ownership of personal data in combination with the right to remix, and

- openness of access with an implied trust of others.

Jenkin's (2006) list of characteristics identifies attributes of the participatory culture includes:

- low barriers to involvement (skill, access)

- acceptance and support of participants (mentoring), and

- assumption of value/significance.

Benefits for Education

So, how do these characeristics, alone or in combination, benefit educators and students?

The participatory web connects learners with other learners efficiently (low barriers to involvement) and optimistically (acceptance and support of participants). Within this environment, learners have ready access to the collected skills and knowledge of the community (collective intelligence) and these resources can be tapped efficiently (access data at a granular level). Individuals contribute what they can to the mix (low barriers, increase in value as users contribute).

Henry Jenkins (2006) (note this is a pdf) challenges educators to involve students with participatory experiences to address some different issues. He notes that:

- not all students have these experiences outside of school and this difference may influence future potential (an equity issue)

- students are often heavily involved with participatory experience and need to understand how they are being shaped by these experiences, and

- participatory experiences may encourage practices that violate standards (e.g., ethics, safe behavior) and an understanding of such issues should be considered.

In the material that follows, we explore participatory web tools and related applications for learning. As a matter of policy, we include in our analysis background material we feel provides a theoretical and empirical foundation justifying our enthusiasm. We also recognize the concerns associated with encouraging young people to participate in the public Internet. Actually, we do not assume today's students need to be encouraged to participate online. In fact, we assume they will participate with or without the assistance of educators or parents and this reality requires a proactive approach addressing responsible behavior.

A comment on the "work in progress" nature of this site

You will find this a work in progress. This would seem appropriate given the nature of the tools and processes we are describing. You may find this an incomplete resource. It will take some time to develop and the intent is to describe what we already know is a rapidly moving target. There are some advantages of a work in progress you might not anticipate. One of the things in writing traditional books (e.g., Integrating Technology for Meaningful Learning) that has long frustrated us has been that the resources were somewhat dated before we ever saw our work in print and this situation only grew worse as we waited for the opportunity to create the next edition. This source will likely not be as polished as our commercial works, but we do hope to make continual adjustments as our time allows.